An Artist’s Epic Journey Across North America To Capture Railways and Ports

Bixby Bridge, Big Sur CA, 2010. (All photos: © Scott Conarroe)

Bixby Bridge, Big Sur CA, 2010. (All photos: © Scott Conarroe)

The US freight rail industry operates across nearly 140,000 rail miles and delivers an average of five million tons of goods each day. The network that was first begun 180 years ago is now part of our landscape, and it is what prompted Canadian photographer Scott Conarroe to first document North America’s transport infrastructure. He spent over four years traveling through Canada and the U.S., capturing not just the vast swathe of railways but also the ports and roads that hug the coastlines.

These expansive panoramas are brought together in his new book, By Rail and By Sea. Photographed in the milky light of dusk and dawn, his large-scale vistas highlight the relationship between the natural environment and industry. Atlas Obscura spoke with Scott about ports on the Arctic coast, suspicious American policemen, and the challenges of shooting a project of this scale.

How did you go about planning and executing the project, given the distances involved?

There wasn’t a lot of planning. I sketched a dot-to-dot of places I was curious about, then I moved into an old van. Money I’d’ve spent on rent went into gas and film. I worked my way south for the colder months, and in spring I’d head back north. Some days I covered a thousand kilometers. Sometimes I hung out for weeks.

The Arctic coast seemed most inaccessible, but in 2011 the Canadian Armed Forces Civilian Artist Program let me tag along on the HMCS Summerside’s operations in Nunavut. There were few occasions I could go ashore, but I made pictures when I could.

RV Parking Lot, Dockweiller CA, 2010.

RV Parking Lot, Dockweiller CA, 2010.

Boat Barn, Belfast ME, 2009.

Boat Barn, Belfast ME, 2009.

What do you find interesting about the interplay between large-scale industry like the railroads and ports, and the natural environment?

I like the different time schemes each portrays. Notions of progress and strength and identity get projected upon industry while the nature we shuffle through en route to that progress is seen as incidental. Railways fundamentally altered our conception of space; they compressed distance like nothing before. Fortunes were made. Lives lost. Indigenous populations were rendered almost extinct. And now railways are quietly absorbed into the landscape.

The relevance of port towns has evolved too. I’m thinking here of my photo “Cruise Ship, Portland ME, 2009.” Portland was once North America’s largest winter port and a substantial rail hub. In this picture though it’s dwarfed by a cruise ship. Industries change. Prosperity comes and goes. We’re particularly vulnerable to this– many of our communities were manufactured to service industry rather than the other way around. And throughout it all, nature keeps exerting itself. Sometimes the flex is incremental; sometimes it’s Sandy or Katrina. If nature wasn’t so interesting, its indifference would be terrifying.

Cruise Ship, Portland ME, 2009.

Cruise Ship, Portland ME, 2009.

Storage Lot, Cochrane AB, 2008.

Storage Lot, Cochrane AB, 2008.

How did you scout for the locations and vantage points from which to shoot?

I’d arrive somewhere I thought I’d like to see, then I strolled or rode my bike around looking for things to climb up on. You’re right to ask about vantage points. These pictures are more about surveying the landscape–how various realities exist in proximity to one another–than about a set of locations that might support some thesis. I’d try to find two perches in each place: one for a dusk photograph and one for dawn the next day.

Bow River, Alberta 2008.

Bow River, Alberta 2008.

Boaters, Kalamalka Lake BC, 2008.

Boaters, Kalamalka Lake BC, 2008.

What inspired you to create this photo series?

By Rail began when I realized train tracks kept cropping up in my pictures of other things. I guess I just like how they look. I knew they were too hackneyed for contemporary art, but I was pretty off the radar so there wasn’t much to lose. I contrived a study of “North America’s rail infrastructure.” This was 2008. The financial crisis had just abated. Hillary or Obama would be president. Peak oil was understood, yet new muscle cars were being marketed. Change was in the air. I wanted to go check it out. Railways were a good motif: they look nice, they weave through several of our society’s foundational moments, and they go everywhere.

It ended up focussing on Canada and the U.S., no Mexico. I developed it into something I was confident about. By Rail started touring around Canada, but I had nowhere to be so I decided to engage another tired trope: the beach at sunset. By Rail and By Sea could have each been books, but I like the idea of rails crisscrossing the continent while a contour line hugs the perimeter. I see the railway section of By Rail and By Sea as commenting on the development of this geo-cultural bloc; the seasides anticipate an era increasingly defined by climate change.

The Coaster, Del Mar CA.

The Coaster, Del Mar CA.

Hobo Camp, Reno NV, 2008.

Hobo Camp, Reno NV, 2008.

The railroads represents the mechanical age and we are now firmly in the digital age–do you think interest in the railways will diminish?

I don’t think mechanical or digital has much to do with it. Railways diminished here because we’re driven by baser instincts. We’re not barn raising folks anymore. We’ve so bought into trickle-down economics that even benign collective actions (riding on a train with one’s neighbors, for instance) has become anathema to some “way of life.”

Railways aren’t a question in other places. In Europe they’re a component part of transportation and communication networks that bolster economic and cultural activities. It’s a more nuanced equation than profit or loss. And China, the foreign creditor we love to mischaracterize, is developing a high-speed rail system as extensive as the Interstates, and as an aside they’re building infrastructure in Africa.

Rail Yard, St Louis MO, 2008.

Rail Yard, St Louis MO, 2008.

Fraser River, NewWestminster BC, 2008.

Fraser River, NewWestminster BC, 2008.

Did you notice a difference between the railways you shot in Canada and those in America?

I probably couldn’t distinguish a Canadian from an American rail. That’s part of what made them a useful device. Like common language and some shared attitudes, railroads are pretty consistent throughout the continent. The perceived threat of landscape photography was markedly different though. When we had to interact, Canadian cops asked about my big weird camera, the project, how long I’d be in town, etc. In America I experienced more clench-jawed bullies freaking out than necessary. So much pointless sitting on the curb.

Forest Fire Plume, Golden BC, 2008.

Forest Fire Plume, Golden BC, 2008.

Monorail Station, Miami FL, 2008.

Monorail Station, Miami FL, 2008.

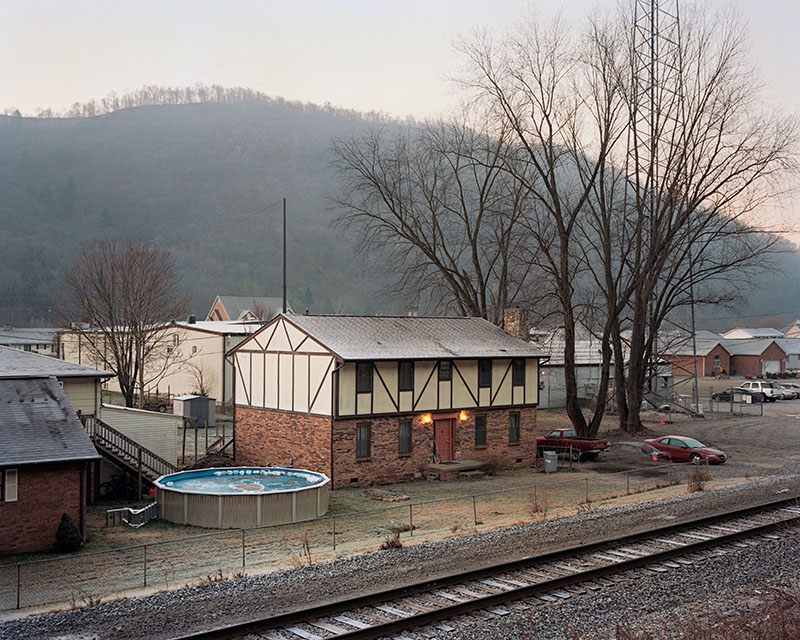

House With Pool, Shrewsbury WV, 2008.

House With Pool, Shrewsbury WV, 2008.

What is the one shot in the series that fascinates you most, and which one was the most challenging?

It’s sparse, but there’s a lot to ponder in “Loop, Biloxi MS, 2010.” First, why does the offramp extend out over the beach into the water? The sub-mystery is who decided to build a little boardwalk along that same route? And then a ways into the middle ground there’s a disembodied punchline: lone palm guarded by orange fence.

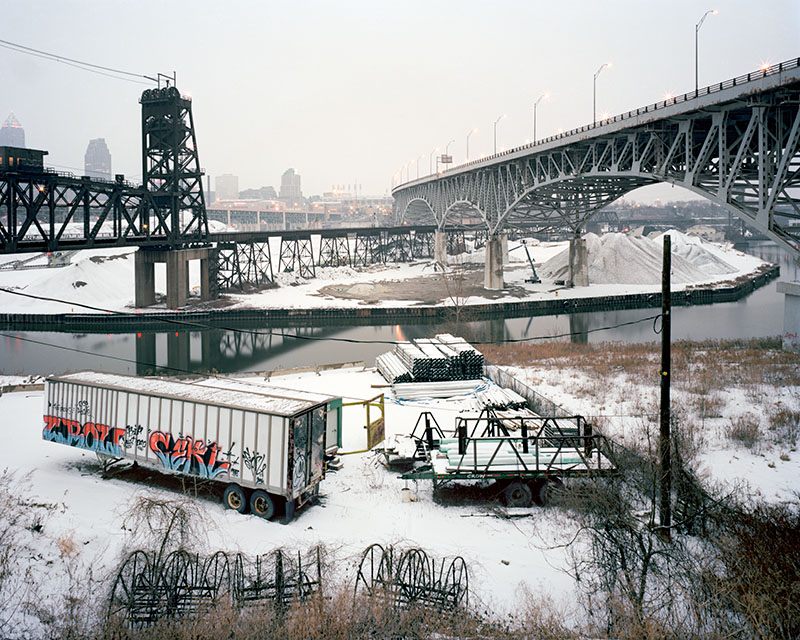

I don’t remember any picture being overly difficult. Sometimes it was cold or there were mosquitoes. Sometimes traffic or lightning or scoundrels made me anxious, but the photographing was usually straightforward. One image that I edited out early somehow ended up a linchpin of By Rail though. I guess accepting the wan “Canal, Cleveland OH, 2008” could be seen as a type of aesthetic challenge. At the outset I imagined a richer palette. Nonetheless, I love how it shows three strata of infrastructure–canal, railroad, and freeway- simply laid overtop one another as different chapters of development occurred.

Canal, Cleveland OH, 2008.

Canal, Cleveland OH, 2008.

Loop, Biloxi MS, 2010 on the cover of Scott Conarroe’s book, By Rail and By Sea.

Loop, Biloxi MS, 2010 on the cover of Scott Conarroe’s book, By Rail and By Sea.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook