At This Lost Alpine Resort, You Could Ski Among California’s Orange Groves

Why choose a winter or summer vacation when you could have both at once?

The “White City” complex at the top of Echo Mountain. (Photo: Public Domain)

Imagine a mountaintop resort that combined snow and orange groves. Where you could go tobogganing among hummingbirds. A place that contained, in the rhapsodic words of journalist and photographer George Wharton James, “[s]nowy mountains and pearly face ocean, hazy islands and Eden’s garden, all held in the bottom of God’s hand, in the sight of one man’s eyes, at one and the same moment!”

Such a place once existed, a mere 25 miles from downtown Los Angeles. Thanks to a blazing inferno, it is no more.

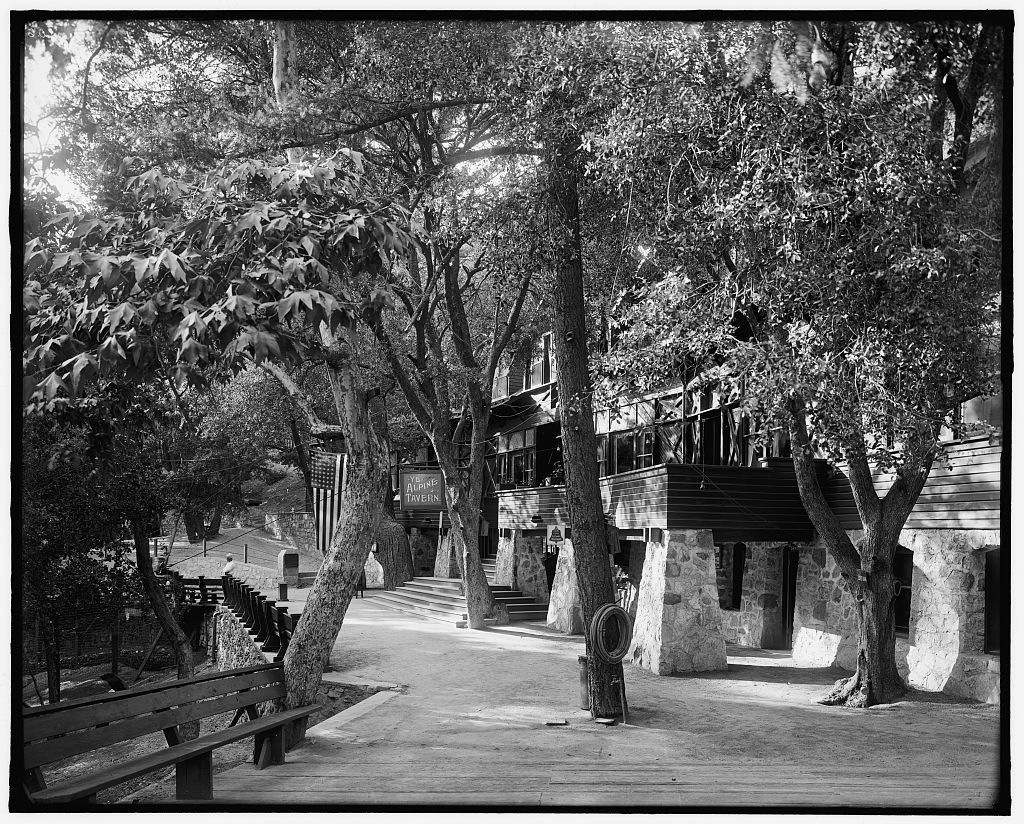

Located 4,420 feet above sea level, just under the peak of Mount Lowe in the lower San Gabriel (also known as the Sierra Madre) Mountains, Mount Lowe Tavern—originally called Ye Alpine Tavern—it was a rambling, rustic Swiss style chalet, surrounded by big cone spruce, pines and oak trees.

Ye Alpine Tavern, c. 1900. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-det-4a25772)

The dream had come to fruition in the boom-time Los Angeles County of the late 1800s. At the time, county boosters had spent years touting Southern California’s warm weather, palm trees, beaches and orange groves. Places like Pasadena and Altadena were already winter havens for wealthy East Coasters and Midwesterners. But as they sat on the sunny porches of their grand hotels, in the distance the San Gabriel Mountains towered above them, often boasting picturesque snow-capped peaks. Why shouldn’t Los Angeles County utilize these mountains and become a world-class all-weather resort?

Echo Mountain. (Photo: Hadley Hall Meares)

The man who would bring these views to the masses had already lived a life of ascending heights. Thaddeus S.C. Lowe attained fame during the Civil War as a daredevil balloonist who had spied for the North, collecting data on many famous battles. After the war, he had turned to inventing and made a small fortune off his creations.

Like so many other wealthy Americans, he had come to Pasadena, in 1888, to retire into a life of entertaining and relaxation. But he was soon visited by a talented young engineer named David J. Macpherson, who dreamed of building an incline railway in the San Gabriel Mountains. The New England born Lowe was enticed by the idea, and in 1892, he and Macpherson began to build the railway and a resort. The L.A. County elite were so delighted with Lowe’s plan—and his willingness to sink his own fortune into it—that they renamed the resort’s highest peak in his honor.

Built in stages, the Mount Lowe Railway and Resort was one of the wonders of Los Angeles County by 1895. Passengers boarded an electric train at the sunny Mountain Junction Station in Altadena, which took them into Rubio Canyon, 1,950 feet above sea level, in the lower San Gabriel Mountains. Here, among sycamores and flowers, they encountered the lovely two-level Rubio Pavilion, set on a narrow gorge. The Pavilion included a small hotel, depot, café and shady porches. More than a thousand steps linked wooden walkways that criss-crossed streams, fern glens, nine waterfalls, moss grottos and attractions like the Mirror Lake, the Ribbon Rock and the Suspended Boulder.

After experiencing the delights offered at Rubio Pavilion, visitors hopped on the great cable incline to Echo Mountain. The incline’s two open cars, called “white chariots,” featured stacked seating to facilitate the best views of the valleys below. In eight minutes, visitors arrived at the summit of Echo Mountain, home to a large complex that became known as the “White City.”

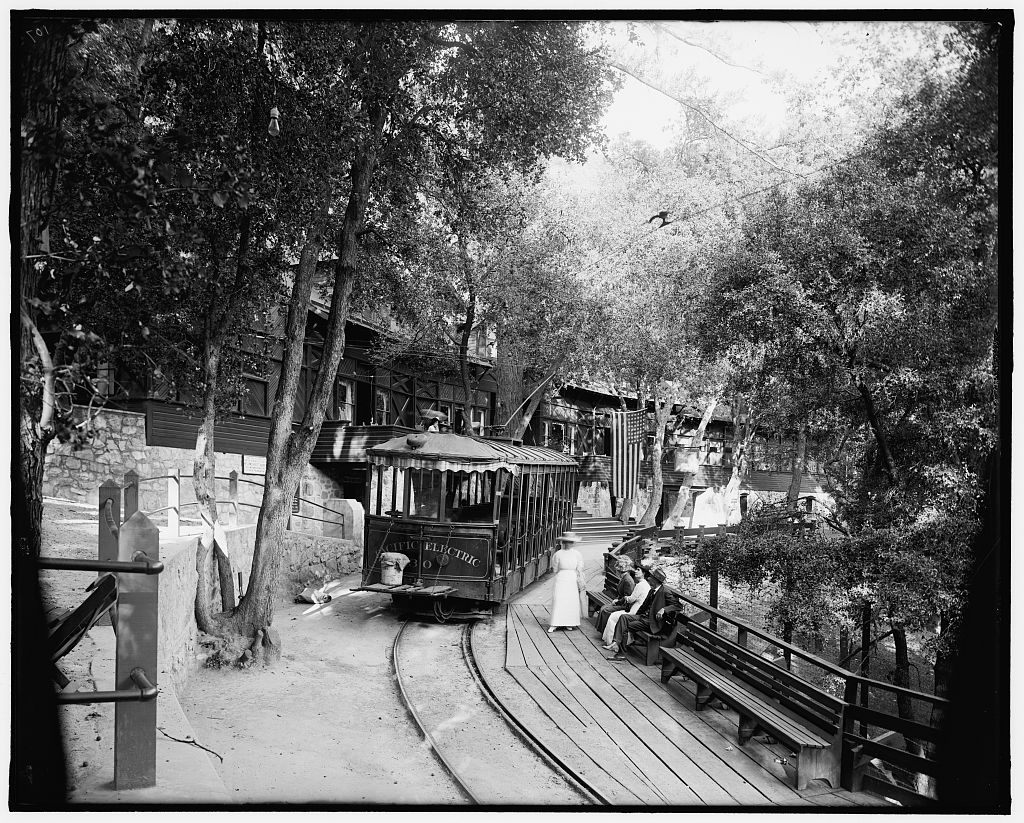

Electric car at Ye Alpine Tavern, Mount Lowe Railway, c. 1900. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-det-4a25762)

This complex of rambling white buildings would over the years include a celebrated Observatory, the beautiful Echo Mountain House hotel, a smaller dormitory, tennis courts, picnic areas, a museum and even a small zoo. One of the great attractions on Echo Mountain was “the great searchlight,” visible from 100 miles away, which had caused a sensation when it originally appeared at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair.

Next up was a trip on the “Alpine Division” cable incline, the “railway to the sky,” which took visitors up 3.5 miles, from Echo Mountain to the Crystal Springs on Mount Lowe.* Recalling his first ride, Harrison Gray Otis wrote that “the road appeared dangerous to the more nervous and timid,” but was reassured that the tracks had been “built in a most thorough and substantial manner and were not made to ‘fall down.’”

Circular railway bridge on the Mount Lowe Railway. (Photo: USC/Public Domain)

Once visitors arrived at Crystal Springs they encountered a scene out of a Swiss fairytale. The chalet-style Ye Alpine Tavern, composed of granite and Oregon pine, featured numerous hotel rooms, grand fireplaces, dining and game rooms. “The forest all about the tavern are giant pines and immense oak trees, their branches touching the very roof of the building,” Otis reported. Outside were cabins for summer dwellers, paths for those wishing to take rides to the peak of Mount Lowe, and snow, which could often be found on the north slope of Mount Lowe from November to May.

When the snow was particularly heavy, visitors thrilled in participating in winter sports that seemed so out of character for Los Angeles County. On New Year’s Day in 1903, “Old Boreas made things howl outside among the snow banks, and sitting around the fire cracking hickory nuts was the most comfortable thing to do,” enthused one reporter. In 1896, the Los Angeles Times, thrilled to talk up L.A.’s wonders as much as possible, reported “great sport sleigh riding, tobogganing and snowballing in the vicinity of Alpine Tavern.” The resort, it said, offered “the novel sport of winter pastimes in sight of oranges and roses.”

Though by far the most expansive and well known, Lowe’s was not the only Alpine resort in the area. At nearby Mount Wilson there were several recreation areas featuring log cabins, hotels, and camping grounds. At Mount Baldy, the tallest mountain in the San Gabriels, there was the rustic Baldy Summit Inn, billed as “the highest hotel in L.A. County.” In 1908, developer Robert Marsh built his own incline railway, which led to his beautiful new resort atop Mount Washington in Los Angeles (now the headquarters of the Self-Realization Fellowship).

Sadly, due to poor management and Mother Nature, the success of most of these establishments would be brief. Despite Mount Lowe’s preeminence and massive popularity (it is estimated that it was visited by over three million people in its 41 years), “the greatest mountain railway in existence” was no exception. Lowe had incurred massive debt, and he officially lost the property in 1899. He died virtually penniless but without regrets, claiming Mount Lowe was “ten years ahead of the times of the country.”

The original sign on Echo Mountain. (Photo: Hadley Hall Meares)

In 1902, Henry Huntington and his Pacific Electric Railway Company came into possession of the railway and resort. They would do much to improve the site, making Mount Lowe part of their interurban railway line and expanding Ye Alpine Tavern (renaming it the Mount Lowe Tavern). But they were dealing in diminishing returns, for nature seemed determined to reclaim her land. Disaster after disaster struck the resort throughout the early 1900s. Roaring fires destroyed all the buildings on Echo Mountain except for the Observatory. In 1909, a violent thunderstorm caused boulders to roar down the mountain, crushing the Rubio Pavilion. A violent wind blew off the Observatory’s dome in 1928, ruining the telescope within.

Ruins of the “White City” on Echo Mountain. (Photo: Hadley Hall Meares)

But the greatest calamity came on a dark evening in 1936. While the guests at Mount Lowe Tavern were all snuggled in their beds, the night watchman making evening rounds spied a flickering glare in the tavern kitchen. He sounded the alarm, and the guests awoke and ran into the bracing night air. Within 10 minutes, the tavern and surrounding cottages were fully engulfed in flames. With the destruction of the tavern, followed by a flood in 1938 that washed away significant portions of the incline track, the four-decade dream of making Los Angeles County an Alpine resort equal to those in New England and Europe was forever dashed.

Rail machinery atop Echo Mountain, (Photo: Hadley Hall Meares)

Today, you can hike the twists and turns of the old railway bed to Echo Mountain and on to Mount Lowe. Hikers can view the expansive foundation of the Echo Mountain House, stone works from the Mount Lowe Tavern, and portions of the old railway line. Though the buildings are gone, the foliage is rich, the air is pure and crisp, and the views are as amazing as ever. You really do feel that you are on top of the world.

*Correction: This article originally referenced an incorrect location for the Macpherson Trestle. It was located on the Great Incline, not the Alpine Division.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook