Pigeon Towers: The Rise and Fall of a 17th-Century Status Symbol

A dovecote at Niort in the Poitou-Charentes region of France. (Photo: dynamosquito on Flickr)

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the richest people across the United Kingdom and France built beautiful towers, just for pigeons.

Known as dovecotes, pigeonniers, doocots, or colombiers, these buildings served as apartment blocks for hundreds of pigeons who were waiting to be eaten by members of the nobility. Early 20th-century pigeon expert Arthur Cooke estimated that by the 1650s, there were 26,000 dovecotes in England alone. Though many dovecotes had similar designs, each had its own flair. In his 1920 Book of Dovecotes—the seminal tome on the subject—Cooke waxed lyrical on the grandeur of the pigeonnier:

“Are not all dovecotes pretty much alike?” it may be asked. The answer to this question is emphatically “No.” It would be difficult to find two dovecotes quite identical in every detail, architectural style, shape, size, design of doorway, means of entrance for the inmates, number and arrangement of the nests. … They were designed and built by craftsmen gifted with imagination, who, though they worked to some extent upon a pattern, loved to leave their individual mark upon the thing they fashioned with their hands.

Dovecotes were used primarily to keep pigeons for their meat. (The birds’ guano was also collected and used for fertilizer, gunpowder, and tanning hides.) At the time, root vegetables had not yet arrived in Britain, meaning that in winter, farmers could not rely on their usual crops to feed livestock such as pigs and cows. They were therefore bereft of beef and bacon, and turned to alternative sources of meat. Pigeons were easy to maintain: as natural foragers, they spent their days seeking food, then came home to roost at night. A farmer needed only to have a tower lined with nest-friendly alcoves in order to keep hundreds of squabs at the ready.

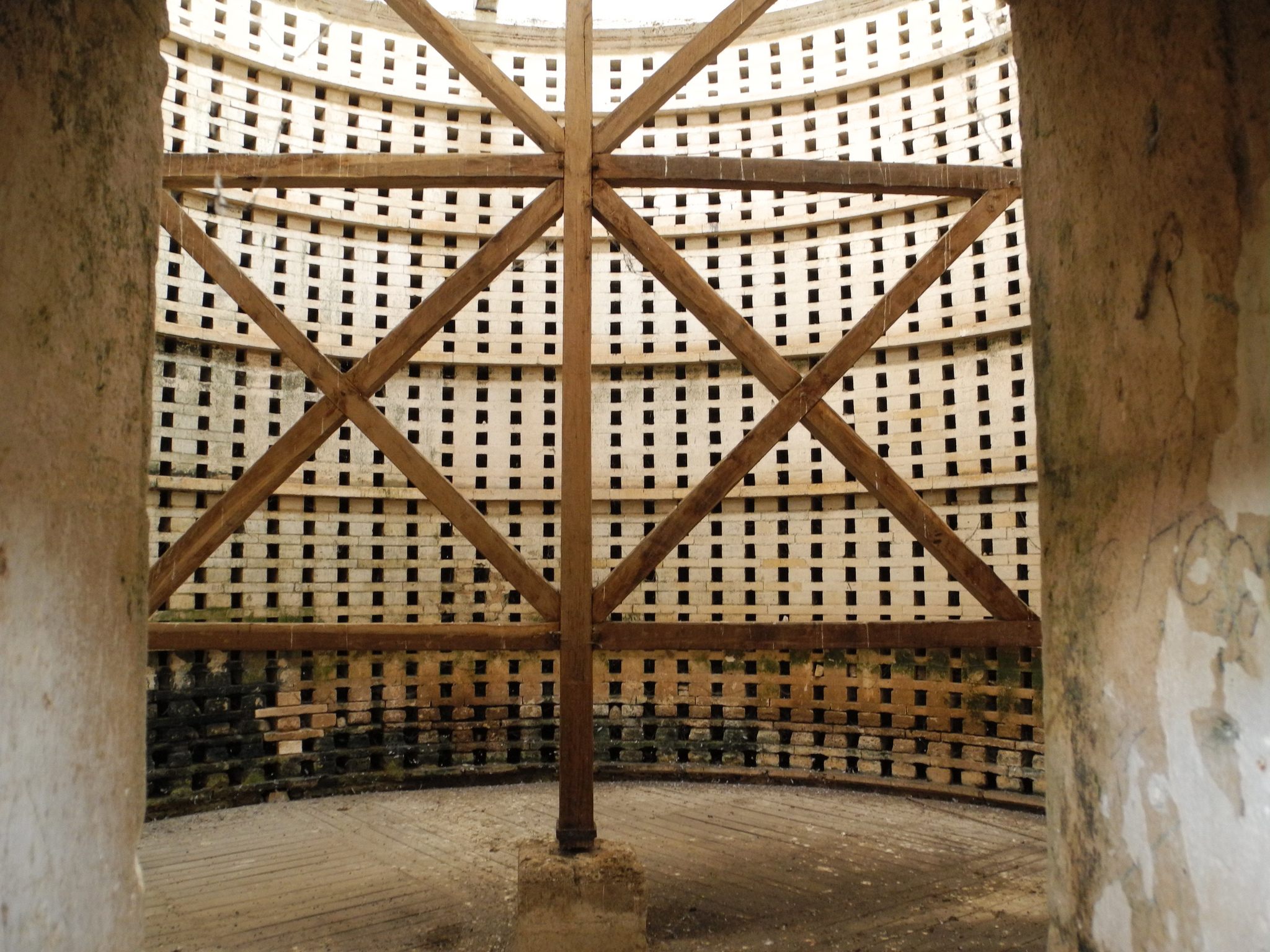

The interior of a colombier on the French island of Oleron. (Photo: pascal_nl on Flickr)

This Elizabethan convenience food, however, was not available to all. “Dovecotes for the time were a badge of the elite,” says John Verburg, a dovecote devotee and self-styled “Jane Goodall of pigeons.” During the reign of Elizabeth I, a pigeon tower was a privilege reserved only for feudal lords. And this law was enforced: Cooke wrote of a case in England in 1577 in which a “tenant who had erected a dovecote on a royal manor was ordered by the Court of Exchequer to demolish it.”

Among the elite crew of pigeon tower people, there was an additional hierarchy. The usual wealth-conscious rules applied: bigger was better, and ornate meant important. “The larger, the more beautiful dovecote, the higher your societal esteem,” says Verburg. “Commoners were not allowed to keep pigeons, and the size of the dovecote one was allowed depended upon status and land ownership.”

Around the mid-17th century, the feudal-lord requirement started to be relaxed a little—in practice, if not in common law—causing a boom in dovecote construction and a decline in the prestige of the pigeon tower. “When that set of rules fell, and commoners were allowed to construct dovecotes, the status element was lost and the incentive to build dovecotes gone,” says Verburg. “We are a vain people.”

A dovecote at Nymans in West Sussex, England. (Photo: sidebog7 on Flickr)

Another innovation then came along to hasten the death of the dovecote: the introduction of root vegetables. “It will be neither jest nor paradox to say that dovecotes were in a great measure doomed when first the turnip and the swede were introduced to British agriculture, early in the eighteenth century,” Cooke wrote. With pigeons no longer needed as a winter food source, dovecotes stopped being built.

Three hundreds years later, many of these pigeon towers still exist, in various states of neglect and disrepair. Using Cooke’s tome as a guide, Verburg, whose interest in dovecotes comes from a “synergism of style, architecture, and, yes, pigeons,” has traveled through England, France, and several other European countries in search of surviving towers. They are still there, dotting the countryside, although pigeons have obviously lost their cachet among the elite. For insight into how far these former status symbols have fallen, one needs only to visit Trafalgar Square or any puddle in Manhattan. Once nobility fought to build huge towers to raise pigeons; now we call them “rats with wings.”

BONUS: Highlights from the dovecoat tour. Cotehele, pictured below, an estate in Cornwall that dates back to England’s Tudor era. The domed dovecote on the premises is dotted with moss and surrounded by wild greenery, giving the whole scene a tranquil feel.

An overgrown dovecote at Cotehele in Cornwall, England. (Photo: Roger Lombard at geograph.co.uk)

The pigeonnier at Planguenoual in France was another highlight, notable for its unusual three-towers-in-one design:

A pigeonnier at Planguenoual in Brittany, France. (Photo: John Verburg)

A pigeonnier at Planguenoual in Brittany, France. (Photo: John Verburg)

France is the prime destination if you’re interested in seeing dovecotes, particularly the Brittany region. Verburg recommends it both in terms of sheer numbers of towers left and the variety of styles on display. ”Many are architectural wonders matching that of the elegant estates themselves,” he says.

A dovecote at Avebury in Wiltshire, southwest England. (Photo: Varun Shiv Kapur on Flickr)

The remains of a doocot in a corn field at Parbroath Castle in Scotland. (Photo: B4bees on Flickr)

Inside a dovecote in Wales. (Photo: Smabs Sputzer on Flickr)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook