Images of Old Russia, From a Color Photography Pioneer

A revolution in the use of filters, way before Instagram.

Photography is an art form with deep scientific roots. In ancient Greece, Aristotle and Euclid both described early pinhole cameras. Renaissance painters, Leonardo da Vinci among them, also used these camera obscura (Latin for “dark chamber”) to understand light and color in their work. And Hasan Ibn al-Haytham, an Arab mathematician, astronomer, and physicist, defined techniques in his Book of Optics that became the precursor for early approaches to photography.

Innovations beyond optics came over the years, especially in the 19th century—daguerreotypes in 1837, dry plates in the 1870s, rollable film in the 1880s. But all, as we know, in black and white. Prints could be hand-colored, and it would take another leap before true-to-life color photography became possible. In early-20th-century Russia, one premier photographer helped pave the way for colored images as we know them, and the Library of Congress has dedicated serious efforts to digitizing and restoring his photo negatives, which contain a detailed portrayal of his country at the time.

Sergey Prokudin-Gorskii was a chemist and photographer, first known for presenting papers on the science of photography as a member of the Imperial Russian Technical Society, the country’s oldest photographic society. After establishing a studio and lab in St. Petersburg, his interest in the limits and freedoms of color photography deepened. This fascination brought him to Berlin in 1902, when he studied color sensitization and three-color photography with Adolf Miethe, a photochemistry professor and practitioner. In 1907, the French Lumière brothers introduced the Autochrome color process, but it remained expensive and difficult, and Prokudin-Gorskii stuck with Miethe’s more familiar process. It involved black-and-white negatives shot and then reassembled with colored filters to produce a full-color image.

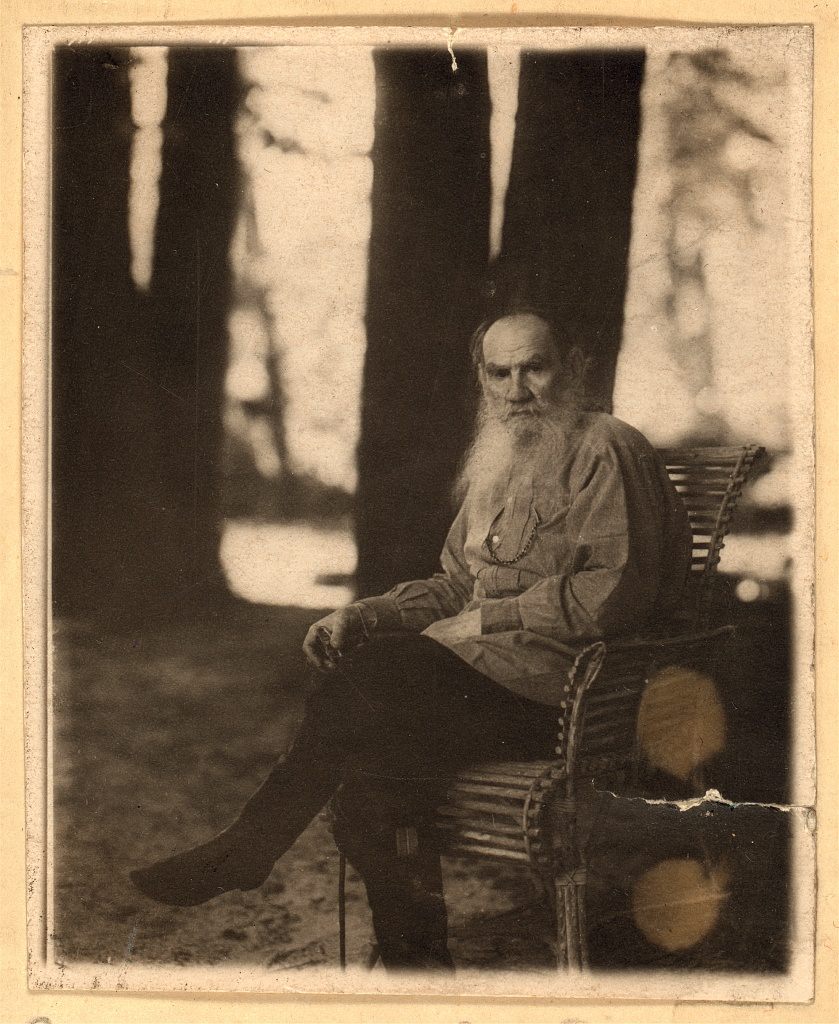

A few years later, Prokudin-Gorskii presented a portrait of revered Russian writer Leo Tolstoy, along with color images of the country’s culture and monuments, to Tsar Nicholas II. So the Tsar funded him and provided special access for him to document daily life using his innovative color photography techniques. Prokudin-Gorskii used a specially designed railroad-car darkroom (outfitted by the Tsar) to produce 10,000 images of the Russian Empire from roughly 1909 to 1915—in particular its farther reaches.

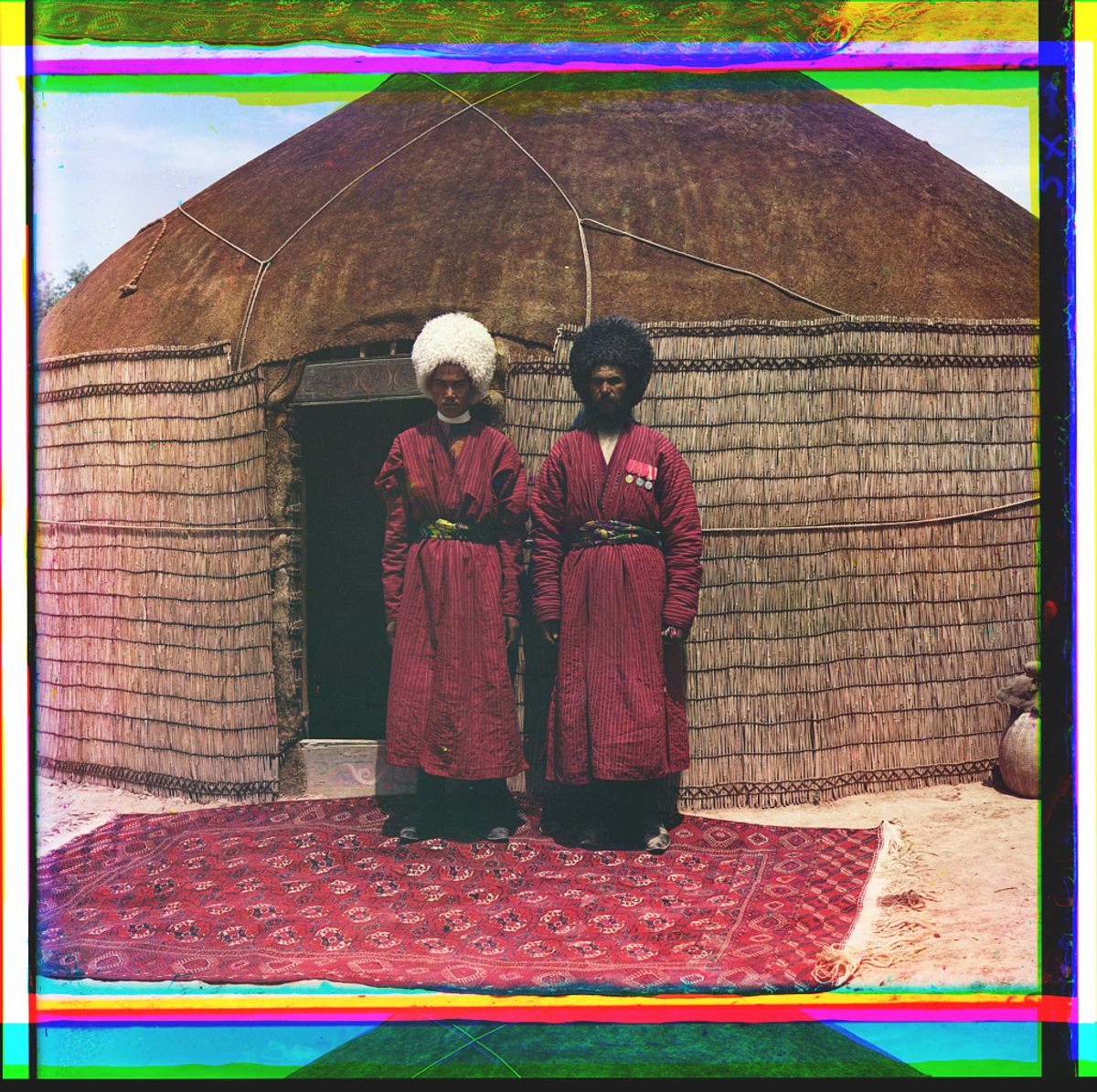

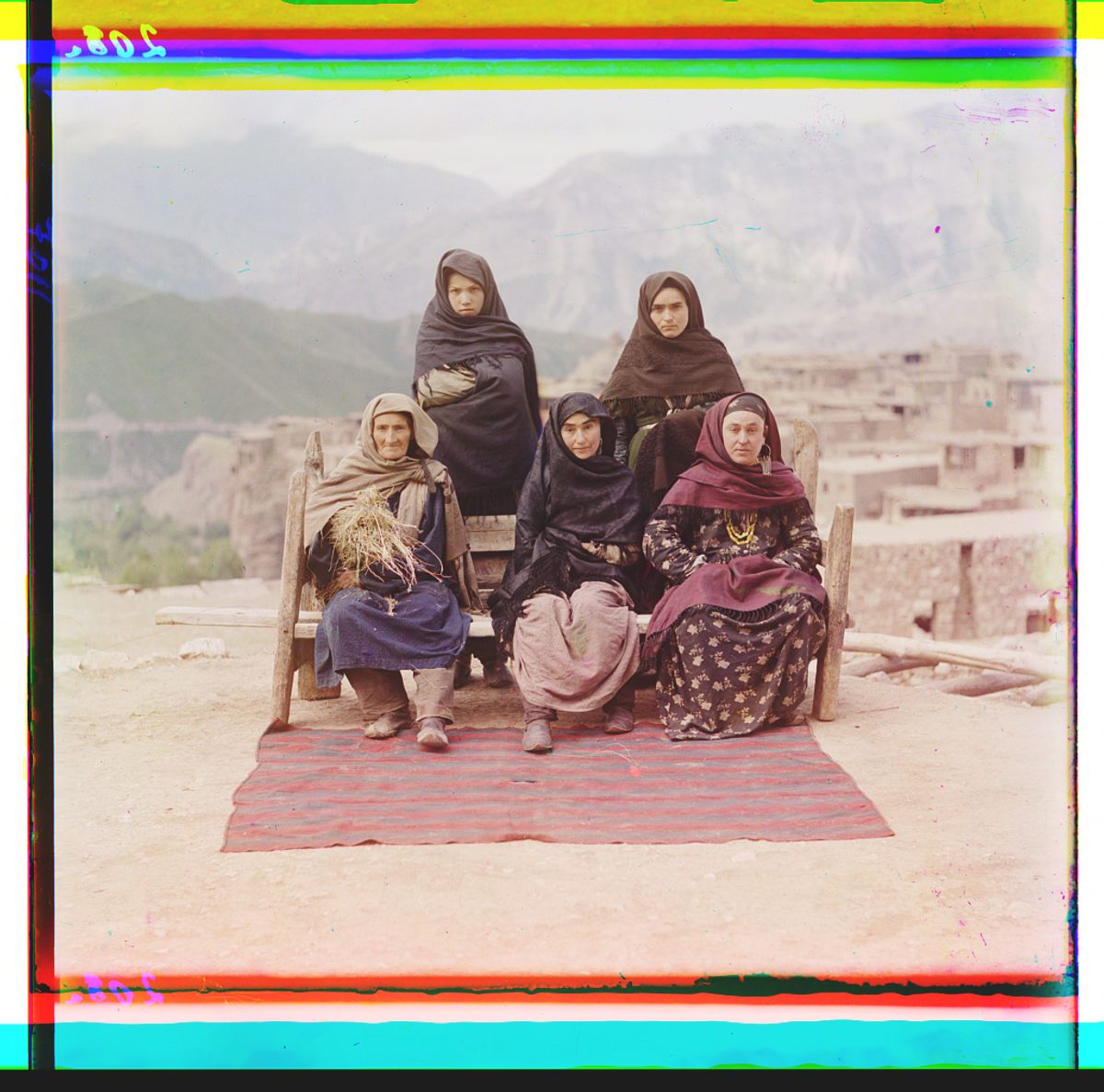

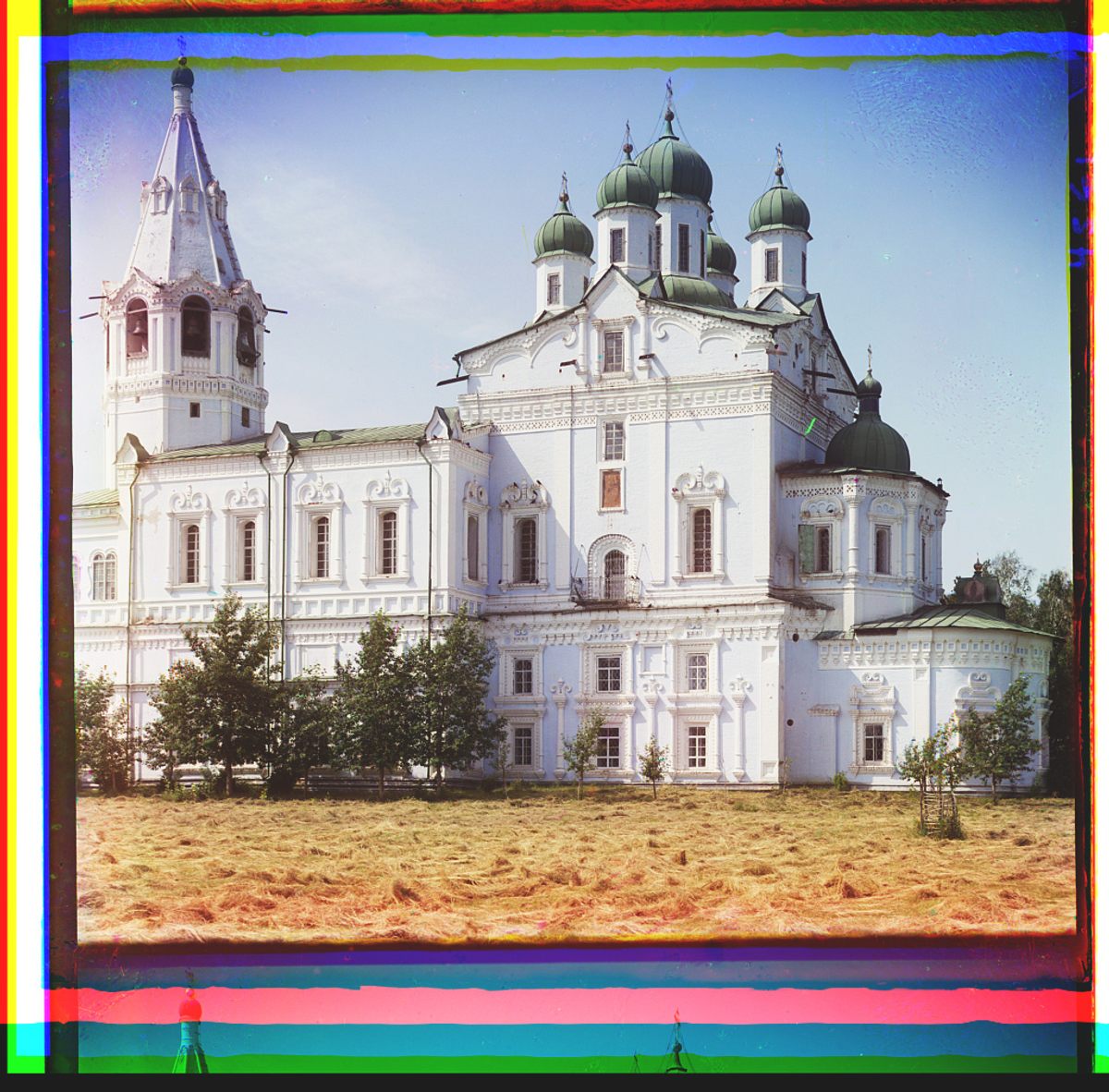

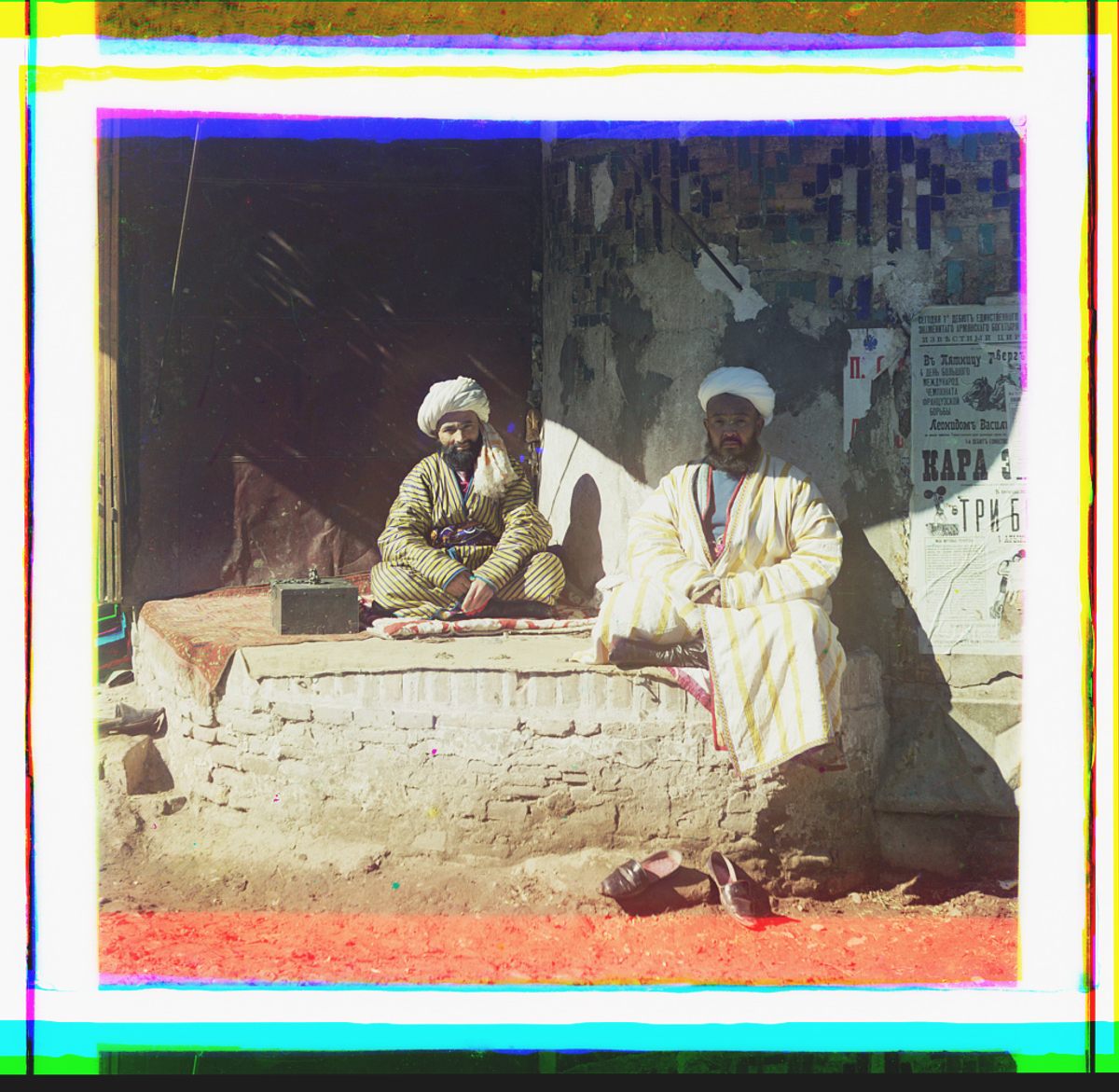

In 1948, the Library of Congress purchased a portion of this historically significant collection of images from the photographer’s sons. “There are 1,902 [images] from black-and-white glass negatives,” says Phil Michel, digital project coordinator in the Prints and Photographs Division at the Library of Congress. “We digitized the entire collection of negatives in the year 2000.” Prokudin-Gorskii’s photographs come from an important time in Russian history: before World War I, and before the Revolution. His renderings of medieval churches and monasteries offer insight to “old world” Russia, in contrast to photographs of the technologically advanced factories of the era. His portraits of the Russian people are vivid and wide-ranging.

“In the early 20th century, when Prokudin-Gorskii photographed his visual survey, the Russian Empire included not only modern-day Russia, but also substantial territory in Eastern Europe, Central Asia and beyond,” according to the curators in the Prints and Photographs Division. “The survey greatly interests both the many people living in this vast region and people elsewhere in the world trying to learn about its history.” In 1922, Prokudin-Gorskii left Russia for Paris, taking his personal inventory—about 3,500 negatives—with him. Half of them were confiscated by authorities who deemed their subject matter too sensitive to leave Russia.

Prokudin-Gorskii’s particular method for color photography, building on the work of Miethe, is known as the “three-color principle,” and simulates the way the human eye deciphers color. Starting with a black-and-white image, “he exposed a glass plate through separate blue, green, and red filters, then used a triple lens magic lantern to project a full-color image,” the curators say. “It took a lot of technical as well as creative expertise in its use of color filters to create on a glass plate three exposures that could later be aligned (registered) into a single color image.” Essentially, Prokudin-Gorskii used a camera that exposed a single glass plate to the three different color filters in succession. Then, by layering the filters, he could produce a single color image. It worked, but it was time-consuming. “In the 1930s, the preferred method became color film with all the color information held in a single frame,” say the curators. “Although modern color photography would evolve using alternative techniques, the imagery created by Prokudin-Gorskii demonstrated the value of color photography for documenting society and culture.”

The process for digitizing the remaining glass negatives was as labor-intensive as it was for Prokudin-Gorskii to produce them. It took the curators nearly six months to complete the initial scanning process of the 1,902 glass plates. The Library then commissioned 122 color prints based on these digital files, with Walter Frankhauser of WalterStudio in Monrovia, Maryland. The digital process, in that instance and in later digitization efforts, was essentially the same as the analog one—superimposition of the three filtered images, with the artifacts of that visible at the edges.

Today, thousands of Prokudin-Gorskii’s photographs of 20th century Russia are available online—the final pivot from analog to digital.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook