The Fashion and Mystery of Ancient Roman Puzzle Locks

Put something complicated, useful, and stylish on your finger.

If you want to send money to someone today, you can just shoot it over with Venmo, but the ancient Romans lacked in convenience, so they made up for it in style. When they sent money, they sometimes secured it with a special trick puzzle padlock that one could wear as a ring.

When we think of Roman fashion today, it’s all togas and laurels, but as preeminent puzzle historian Jerry Slocum and his colleague Dic Sonneveld explain in the recent book Romano-Celtic Mask Puzzle Padlocks, some Romans probably also wore intricate mechanical rings, which they could also use to lock up a money pouch or small safe.

Slocum has spent a lifetime studying and collecting mechanical puzzles. The lion’s share of his collection (some 40,000 puzzles and related items) was donated to the Lilly Library at Indiana University—where it became the Slocum Puzzle Collection—in 2006, but his fascination with the world of brainteasers has never dimmed. “Among what I collected were padlocks with tricks to open them as part of the security,” says. But it was just a few years ago that he discovered the existence of ancient Rome’s puzzle padlocks. “I was quite eager to acquire some,” he says.

Slocum had amassed hundreds of trick padlocks over the years, but by his estimation, the oldest he’d found dated to the 17th century. So when an acquaintance told him about padlocks with hidden levers and catches from the time of the Roman Empire, he was a bit incredulous. “Personally I didn’t believe him,” he says. So Slocum began digging into archaeological journals and, sure enough, there they were. He eventually tracked down a collector. “He had been collecting originals, most of which were just parts. Having been buried for 2,000 years, they weren’t in very good shape,” says Slocum.

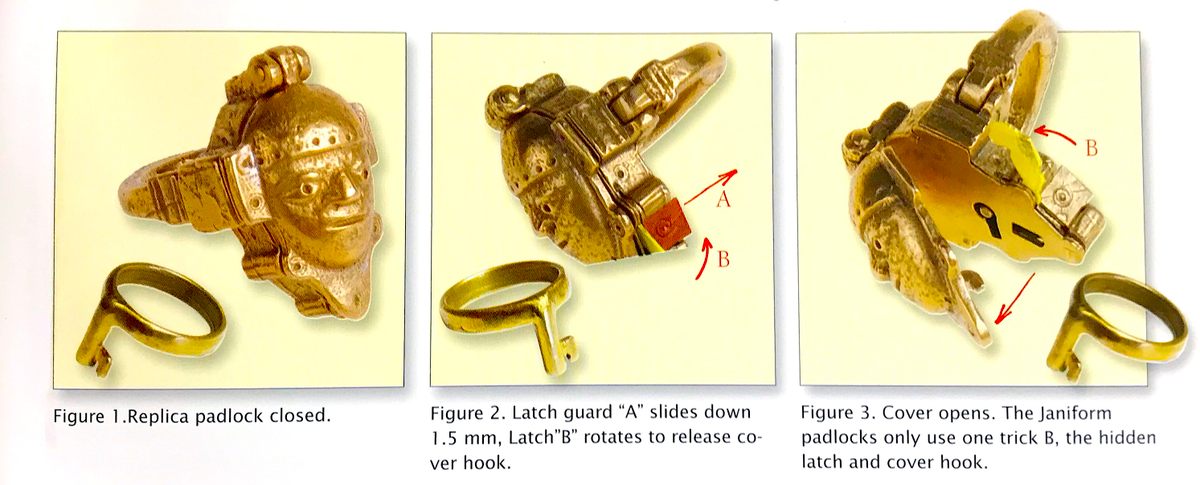

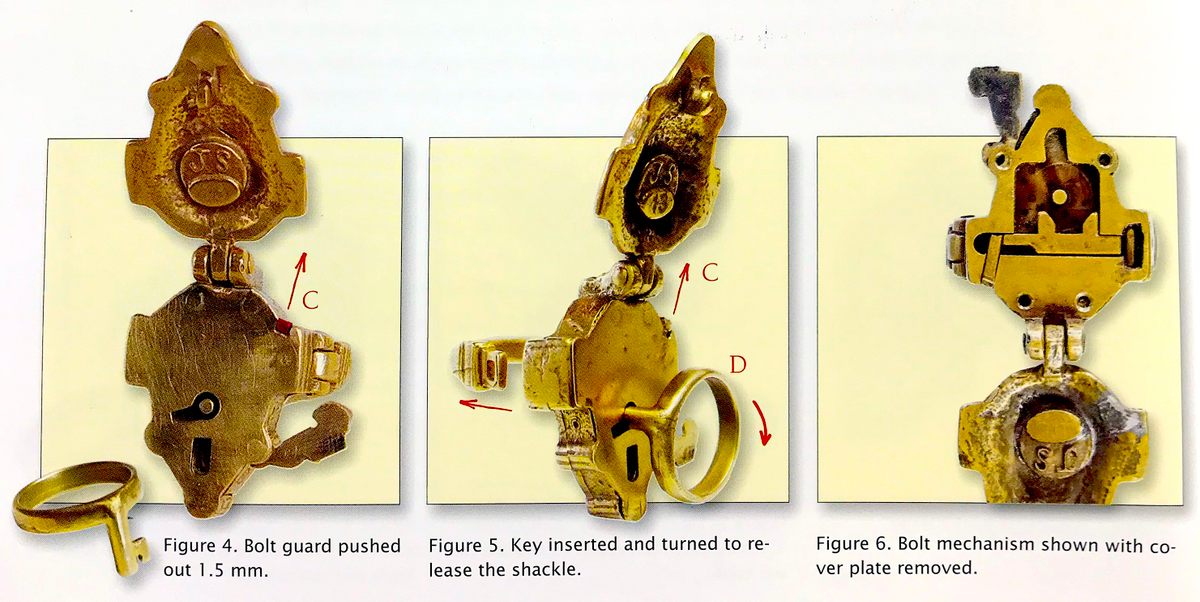

Slocum eventually identified 156 examples in museums and collections around the world, while developing his book on the subject. An impressive variety of padlocks have survived from the ancient Roman world, but this type of puzzle lock has a few distinctive features. Each about the size of a large ring, the locks were usually made of bronze and featured a faceplate sculpted into the image of a god. Janus, god of transitions and passages, was a popular subject. With few exceptions, the faceplate was hinged at the top, and flipped up to reveal a keyhole, the key to which was also sometimes crafted into a ring, worn separately. But the key alone was not enough to open one. The locks also hid one or two tiny little plates or switches that needed to be moved before the shackle—the hoop of the ring—would open. They were more akin to puzzle boxes than modern Master Locks.

The earlier mask locks, as they’re also called, have fewer trick switches, and seem to have originated from regions that were influenced by Celtic culture, such as Aquileia, near the Julian Alps. Slocum posits that the locks grew more complicated as the Romans adapted them.

The small locks are thought to have been used primarily to act as tamper-proof seals. People sending money from one place to the next could secure a leather pouch with one of the puzzle locks, so long as the intended recipient knew the secret and had the key. The locks didn’t necessarily protect the contents, but they provided proof that the delivery hadn’t been messed with—like night-deposit bags used by businesses today.

The locks that have survived today have a small variety of types of shackle—from squat and square to flexible, segmented chains—but the vast majority are round like a ring. After comparing their size with that of known rings of the era, Slocum believes that they were almost certainly worn on the hand. Once the secure package was delivered, the courier might wear the lock as a piece of jewelry to return it to the sender, or the owner might simply wear it when it wasn’t in use.

According to Slocum, use of the puzzle padlocks died out around the 3rd century with the decline of the Roman Empire and its currency. None of the existing examples are in working order, but Slocum had some replicas made. “I wanted to understand how they worked, and how good the puzzles were,” he says.

We might not put as much art and craft into exchanging money as the ancient Romans did, but their intricate work is a good reminder that a little mystery can turn something as mundane as a padlock into a fascinating treasure.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook