The Black Taxidermist Who Made History at Chicago’s Field Museum

A new exhibit celebrates the life and work of Carl Cotton.

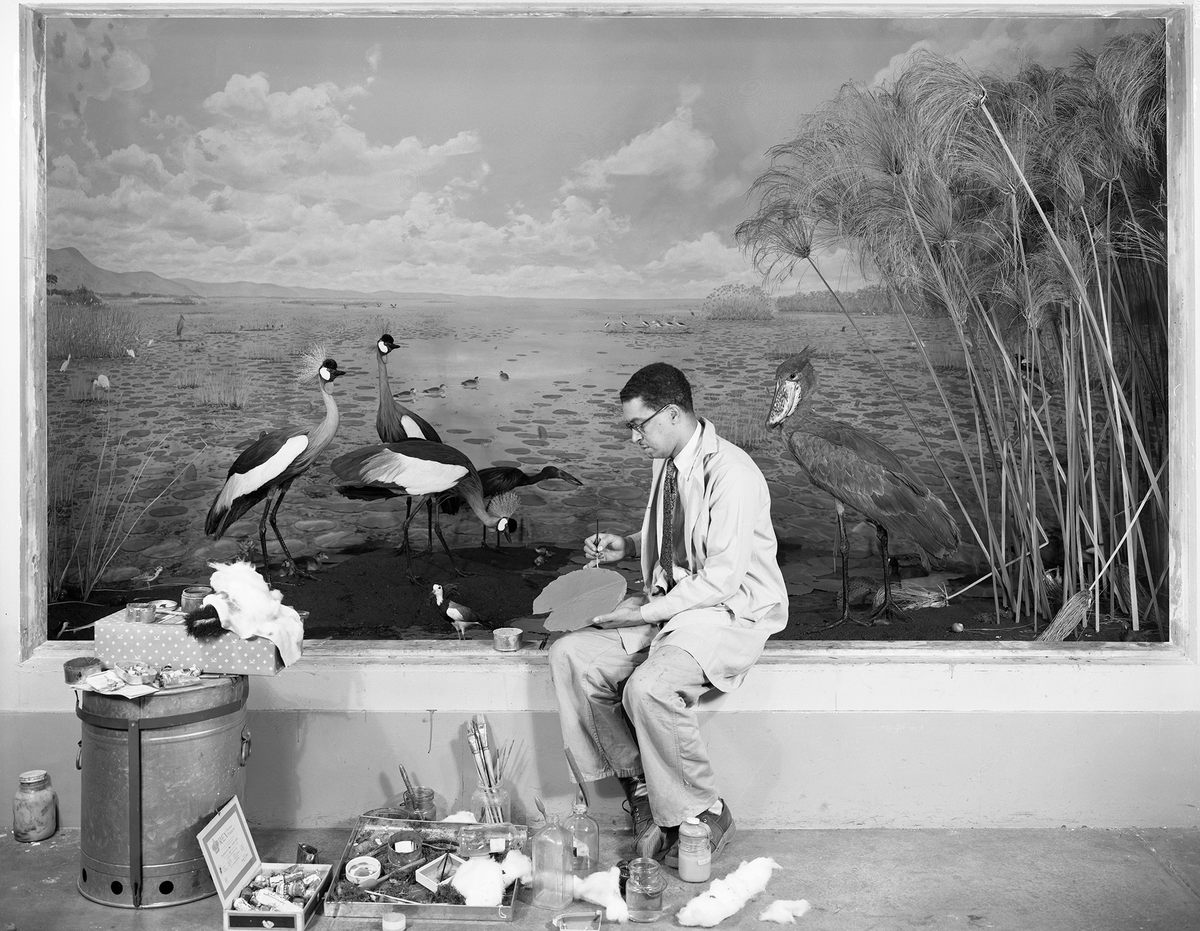

In a grainy, 1950s film from the Field Museum of Natural History, in Chicago, a man gently washes the remains of a weaver bird. The bird is dead, but the act is tender. He dries it with compressed air, stuffs it, and mounts it with wire in the museum’s diorama of African marsh birds. The film shows a number of people working on the diorama; all of them are white, except for the man stuffing the birds. His name is Carl Cotton, and he was the first African-American taxidermist to work at the Field Museum. For nearly 25 years, until his death in 1971, Cotton helped immortalize many of the animals that are currently on display at the museum.

Cotton has now become the subject of an exhibit at his former workplace, A Natural Talent: The Taxidermy of Carl Cotton, which is open until October 4, 2020. “The exhibit shows the human history behind displays that have been here for decades and decades,” says Kate Golembiewski, a science communicator at the Field Museum. “It’s amazing to be able to show a person who bucked the mold and made such a huge impact on the museum.” Tori Lee, an exhibition developer at the museum who curated the exhibit, adds, “Carl was unique in his ability to do everything well.”

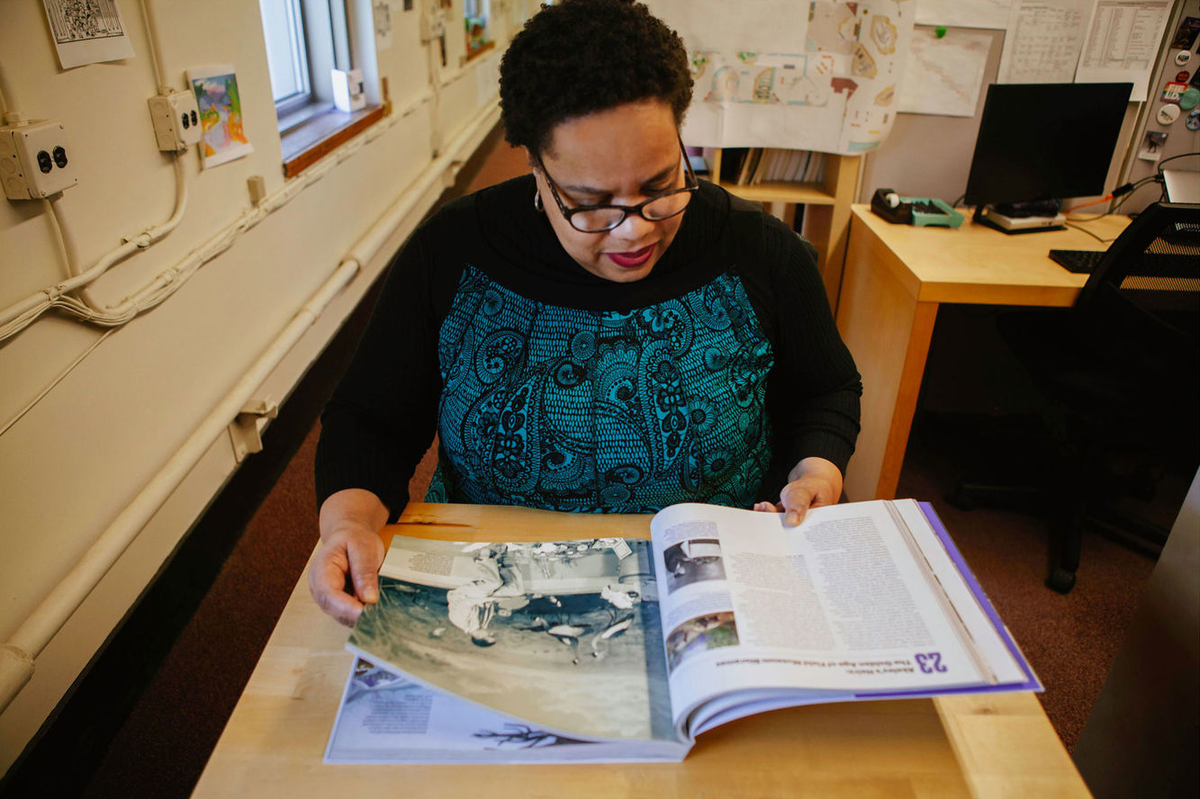

The seed of the exhibit was planted when Reda Brooks, a budget coordinator in the museum’s exhibitions department, began looking into the archives for stories to spotlight during Black History Month, which the museum had never officially celebrated before. In the museum’s 125th anniversary book, she noticed a photo of Cotton preparing the Nile marsh diorama. “Reda showed me the photo and we were both shocked,” Lee says. “I consider myself a muse,” Brooks jokes.

Lee worked with Mark Alvey, the museum’s academic communications manager, to gather all the information that they could find about Cotton. “A lot of people had seen photos of him in the archives over the years, but no one knew a lot about how he came to work here,” Lee says. The duo scoured Ancestry.com and local obituaries for any trace of Cotton, and the museum’s social media team invited the public to share stories about Cotton. Soon, a number of Cotton’s friends and family reached out, and a portrait of his life began to take shape.

Cotton was born in 1918 and grew up in Washington Park, on the South Side of Chicago. He took up taxidermy at a young age and practiced on squirrels, birds, and dearly departed housepets, according to a video interview with Cotton’s childhood friend, the historian and civil rights activist Timuel Black, that plays on loop in the exhibit. He visited the Field Museum for the first time on a school field trip, Brooks says. Cotton worked as a stenographer and served in the U.S. Navy during World War II, but taxidermy remained his life’s passion.

When Cotton first applied for taxidermy work at the museum in 1940, he was turned away. “The director of the museum replied and said, ‘If you want to be a curator here, you need to have a PhD, you need to have made yourself known in the field,’” Lee says. When Cotton reached out again in 1947, he made his passion clearer and also volunteered to work for free. “My ambition is … not doing just ‘average’ taxidermy but turning out work comparable to that of Carl Akeley, Leon Pray, Leon Walters and other artists,” Cotton wrote, referencing the big-name taxidermists at the museum. The Field Museum hired Cotton part-time in the division of vertebrate anatomy, where Cotton did grunt work cleaning skeletons and preparing skins. He was promoted to full-time just a month later.

Lee watched the video of Cotton preparing the marsh birds many times while researching the exhibition. “It’s an incredible video of him working, but there’s no sound and you don’t hear him at all,” she says. “It made him kind of this silent figure for me.” When she read Carl’s 1947 letter, she couldn’t help but tear up. “He suddenly became a person with a voice, who really cared about what he did and wanted to get better,” Lee says, adding that the letter reminded her of her own application to work at the museum.

Cotton quickly rose through the ranks, Lee says. He worked mostly with birds, developing an exhibit on adaptive coloration and redoing much of the bird hall, but soon was called upon to work on the trickier reptiles and fish, as well as repair the larger mammals that had been taxidermied by Carl Akeley. Cotton also developed newer, experimental forms of taxidermy for animals with hairless skin: For example, he replicated a snapping turtle out of cellulose acetate. He was skilled at crafting plants, such as the lily pads in the Nile marsh diorama. “He went above and beyond what typical taxidermy was doing at the time,” Lee says.

While researching the exhibition, Lee was able to identify several of Cotton’s taxidermied specimens that were scattered around the museum with no labels. One specimen, a brown bittern hiding among brown reeds of grass, had been sitting in a classroom that Lee uses frequently. Now, all of Cotton’s known specimens on display are attributed to their creator, Golembiewski says. Cotton’s most famous work, Marsh Birds of the Upper Nile, remains on permanent display. “It’s one of the most famous and iconic pieces at the museum,” Brooks says.

This retrospective marks the first show Lee has curated at the Field Museum. “I’m not technically a curator, and making this show is outside my own job description,” she says. “It was a labor of love.” While the staff of the Field Museum has grown more diverse since Cotton’s days, Lee says there are still institutional barriers to entry for prospective curators of color, including the PhD that was expected of Cotton so many years ago. “That’s why places like the exhibitions department are more diverse than the curatorial department,” she says.

When the Field Museum was founded in 1921, it perpetuated the colonialism and scientific racism on which natural history was built. “Typically people of color were people on display at the Field Museum, seen as others, people to look at and study and examine, and not as scientists and not researchers in their own right,” Lee says. Races of Mankind, a 1933 exhibit that commissioned 104 bronze sculptures of people from around the world, “drew overt connections between race, biology, and hierarchy, making scientific racism a primary framework for the exhibition,” writes Lucia Procopio in “Curating Racism: Understanding Field Museum Physical Anthropology from 1893 to 1969,” published in The Museum Scholar in 2019. The exhibition stayed up until 1969, which included 23 years of Cotton’s tenure at the museum.

Like many other natural history museums, the Field Museum has begun to reckon with this ugly history. In 2016, the museum opened a new exhibit that contextualized the racist history of the sculptures and identified many unnamed subjects. In October 2018, the museum announced a three-year redesign of its Native North America Hall, which originally opened in the 1950s under the name Indians before Columbus. The new exhibit, set to open in fall of 2021, represents a collaboration between museum curators and Chicago’s Native community. The museum is located on the traditional land of the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi peoples.

Lee is hesitant to call Cotton the first black taxidermist in Chicago, though she hasn’t found any others just yet. She doesn’t know whether Cotton was aware of other taxidermists of color, such as John Edmonstone, a formerly enslaved black man who taught Charles Darwin how to taxidermy birds. Lee hopes his story resonates with Chicagoans and inspires the museum to tell more stories about people from the African diaspora. “He grew up here, was raised here, and his family is still in the area,” she says. “It just felt like a good story that in some ways was uncomplicated in its goodness, about a good guy who loved his work and followed his dreams.”

Lee works on the fourth floor, which is the same floor where Cotton once worked. Nowadays, she recognizes bird specimens prepared by Cotton on display in conference rooms and common areas where she and Brooks eat lunch. “Sometimes when you work in a place that’s really old, you forget how many people have walked these halls,” Lee says. “It feels like he was here just the other day.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook