A First Nation, a Fight for Ancestral Lands, And an Unlikely Alliance

The Tseshaht people are working with archaeologists to write a new chapter in a fraught history.

When Ken Watts was a teenager, he spent summers on the ancestral land of his people: a remote island in the Broken Group, off the west coast of Vancouver Island. Getting there was cumbersome—the route included a car, ferry, and boat—but it brought him to the best job he could imagine. Each day, Watts and a few dozen others excavated sites around C̓išaa, a historic village of the Tseshaht people on what is today called Benson Island. By carefully digging and screening every bucketful of earth, they uncovered thousands of pieces of the past.

Watts and his fellow excavators found animal remains, such as clam shells and fish bones and a whale skull with a point embedded in it. They also found human-made artifacts, including a carved comb and an obsidian point. Denis St. Claire, one of the directors of the Tseshaht Archaeological Project, held the dark stone up to the sun. The edge was so thin that the light went right through it. “It was like something in a book or a movie,” Watts says of the experience, which took place in 2000 and 2001. “I was blown away by all those things.”

Everything Watts helped unearth—the shell middens and artifacts and animal bones—had been touched by the hands of his ancestors. Long before the land was seized by Canadian settlers and deemed a part of British Columbia, the village of C̓išaa was the birthplace of the Tseshaht. This field work proved they had lived on the island as long as 5,000 years ago. “There’s very few people in the world who can pinpoint their exact location where the first man and woman were created,” Watts says. “There’s not a lot of other cultures or people that can say, ‘This is where we come from exactly, this island.’” For the first time in his life, Watts could say that about his own ancestors, and could stand on that same ground.

Yet for centuries, the island hadn’t been treated as the motherland of a people. As with so many Indigenous groups around North America, the Tseshaht were subjected to foreign diseases, rapacious Western traders and settlers, and, with the entrance of British Columbia into the Canadian Confederation in 1871, federal policies aimed at the destruction of First Nations peoples.

The Tseshaht never signed a treaty to cede their traditional land, but starting in 1903, the island where the Tseshaht were born was claimed by settlers. It passed from the hands of one Canadian landowner to another. In the 1970s, it came into the possession of the Canadian government, joining the rest of the Broken Group as part of the Pacific Rim National Park Reserve. “Benson Island” became a campground for kayakers.

“Since the creation of the park, the emphasis has been on the natural environment and an attempt to provide a ‘wilderness’ experience for the park visitors,” write Alan McMillan and Denis St. Claire in their 2005 report on the Tseshaht Archaeology Project. “To the Tseshaht, however, these islands are not a wilderness but a homeland.”

The Tseshaht homeland once encompassed numerous villages on many islands, and it supported a population that numbered in the thousands, if not tens of thousands. The Tseshaht were essentially evicted by European diseases and Canadian policies, and their land now serves as a recreational site for the descendants of settlers.

For Watts, returning to the island of his ancestors was almost like escaping the rest of the world. At the time, most people didn’t have cell phones, and social media was in its infancy. Every morning, Watts crawled out of his tent and onto the land. Almost every evening, he sat on the beach with other crew members, including some of the older Tseshaht who knew more about the nation’s history. “I was like a sponge for two summers,” Watts says. “Here I am, fresh out of high school, becoming so connected to where I come from.”

But that sense of earth-deep connection only lasted as long as the archaeological project. At the end of those summers, Watts went home. The island was too logistically complicated to visit after that.

In Canada, a national park with “reserve” status, like Pacific Rim, connotes ongoing negotiations between the federal government and Indigenous groups over the status of the land. Though First Nations retain some rights to hunt and harvest resources in what would otherwise be protected territory, management is a contested issue. In the case of Pacific Rim National Park Reserve, the Tseshaht and eight other groups, all from the 14-member Nuu-Chah-Nulth Tribal Council, have traditional territory inside the park.

In 2000, many felt that these limited rights were no substitute for the autonomy that First Nations peoples once enjoyed. The three-year archaeology project on C̓išaa aimed to right some of those wrongs. With support from anthropologists and the Parks Department, the Tseshaht set out to prove just how deeply entwined they were with the islands—and why they deserved to manage the islands’ future.

It wasn’t so long ago that anthropologists routinely exploited Indigenous communities in the U.S. and Canada. In 1897, archaeologist Harlan Smith wrote, “Indians here object to my taking bones away. They are friendly and will allow me to dig graves and take all but the bones. We hope they will change their minds and allow bones to go to NY for study.” As a member of the Jesup North Pacific Expedition, he and others were tasked with documenting the Native peoples of the Pacific Northwest, and ultimately did take ancestral remains away from the region.

Across the Americas, scientists robbed graves, pillaged cultural items, and at times trafficked in baseless theories about the inferiority of Indigenous people. There were exceptions, of course. Anthropologists like Edward Sapir did invaluable work among the Nuu-Chah-Nulth, creating linguistic documents and records of important oral histories. But all too often, and for much of the 20th century, archaeology inflicted harm in the name of scientific knowledge.

This history made archaeologists unlikely allies in the fight to reclaim First Nations lands in British Columbia. But the Tseshaht Archaeology Project had a track record: Its leaders, Denis St. Claire and Alan McMillan, both white, had been working in the region for decades, talking to elders and asking for the approval of Nuu-Chah-Nulth leaders. Their work came at a time of tidal change in the field, when a growing number of researchers began working collaboratively with First Nations, rather than exploiting their history and territory. St. Claire was even adopted into the Tseshaht, and given the rare opportunity to speak on behalf of the tribe. “They’ve always been so respectful,” Watts says of the men. They wanted to do archaeology in service of the Nuu-Chah-Nulth.

The 1999-2001 archaeology project was meant to create a gateway for future collaboration, and to provide evidence that the Tseshaht could use in an Aboriginal Title and Rights case—arguing, in short, that they had never ceded any territory, and have managed this land for thousands of years. But at the time of the project, the question of how the finds might change the park itself was anyone’s guess.

Karen Haugen, a member of the Huu-ay-aht First Nation and current superintendent of Pacific Rim National Park Reserve, began working for the park in 2003, shortly after the Tseshaht Archaeology Project was completed. The park had already moved toward more cooperative management, Haugen says; in 2009, it closed Benson Island to overnight campers. During her tenure, parks staff began meeting quarterly with all the Nuu-Chah-Nulth Tribal Council nations, including her own. The hope was that by making time to talk, they could address problems early. “We are tight on time, but our First Nations partners are just as tight,” Haugen says.

Pacific Rim National Park Reserve and the Tseshaht have now been holding cooperative management meetings for seven years. Considering that the Nuu-chah-nulth nations had absolutely no say in what happened to their traditional lands in the park up to 1990, this may seem to be enormous progress, and at least a partial success of the 1999-2001 Tseshaht Archaeology Project. The park now includes a Nuu-Chah-Nulth trail and other opportunities for learning about the First Nations whose territory falls within the park.

Watts agrees that the relationship between the nations and the park has deepened and become more fruitful. “I’m pretty proud of some of the things we’ve done with Parks,” he says. But there is plenty of work left, from small issues like financial support for year-round monitoring of the islands, to the large issue of reconciliation with the federal government. On this point, Watts has strong opinions: “You want to talk about reconciliation, how about you give us our land back?”

This complicated problem is largely out of the hands of the National Parks. The Canadian federal government has been reviewing sovereignty claims for decades, and in certain cases, centuries. As the Métis writer and lawyer Chelsea Vowel explains in Indigenous Writes, “The claims landscape out there is vast, difficult to understand, and not very effective.” The three-year Tseshaht Archaeological Project was a way to gather information, but so far it has not forced Canada to return land that it stole.

Still, there are steps the National Park staff could take to help lift up the Tseshaht and their history. As anthropologist Kelda Jane Helweg-Larsen writes in a 2017 paper on the subject, “Co-management is an ideal to strive for, but by and large it has not yet been realized in Canada.” Finances, staffing decisions, and key aspects of management still reside in the hands of the Parks department. Watts offers one example, saying that the park could update their current signage. The park’s maps continue to use names bestowed by Western explorers: Benson, Effingham, Keith, Clarke. But all of these islands, including some of the “unnamed” ones, had already been named and described by the Tseshaht hundreds of years earlier. The restoration of original names would change the way that visitors understand the history of the islands.

In the 20 years that have passed since the excavations of C̓išaa, archaeology has become a cornerstone of how the Tseshaht assert their history and modern presence in the park. Archaeologists have repeatedly come back to Tseshaht territory, doing research from 2008 to 2011 at village sites on the Hiikwis reserve, which was threatened by logging, and from 2015 to 2016 on Jaques Island.

In the summer of 2019, archaeologists gather with Tseshaht visitors on Kakmakimiłh, also known as Keith Island, which hosts an annual field school through the University of Victoria. For several weeks, Kakmakimiłh hums with human voices and the sound of a generator. The island includes a dock, a gazebo, several outhouses, and a cabin for the Beachkeepers, seasonal Tseshaht employees who patrol the surrounding islands to protect heritage sites and provide park visitors with information. Tseshaht community members have started visiting more regularly, but there’s still no running water or electricity. It takes a certain amount of logistical organization to transport people down the Barkley Sound from their homes in Port Alberni.

“Not everybody has the chance to get down here on a regular basis. So welcome home,” says St. Claire, at a sunny, mid-July gathering of Tseshaht community members who have come out for the day. Tan-skinned, white-haired, and wearing a gray zip-up sweatshirt printed with the Tseshaht crest, St. Claire, 72, walks with a cane now; he’s been putting off knee surgery because he worries the recovery will force him to miss a field season. (This current project, which brings students from across North America and is coordinated through Tseshaht First Nation, is slated to last till 2022.)

After St. Claire and his co-director, Iain McKechnie, finish their welcome, tribal member Aaron Watts, a cousin of Ken Watts, sings a song accompanied by a drum, and a small group heads to the forested interior of the island. Students working on four pits have unearthed artifacts from as long as 4,000 years ago, and from as recently as the 1900s. Each year since the project started in 2017, the results have been presented to members of the Tseshaht. They serve as proof of continuous habitation, to help the nation bolster their ongoing legal case for sovereignty.

“I think of archaeology as a crucial step towards orienting ourselves in the present,” said McKechnie, who works at the University of Victoria and has been coming out to this region every summer for nearly a decade. “Even though they’re square holes in the ground, and we’re picking stuff out of a screen, all of it is the beginning of a bigger story.”

For now, even if the archaeology projects can’t completely remake the relationship between Pacific Rim National Park Reserve and the First Nations within its boundary, the work is still providing tangible benefits to the Tseshaht community. Over the years, research has documented the scale of Indigenous clam fishing and its long-term sustainability; it’s proven that the Tseshaht and Nuu-Chah-Nulth spun wool from domesticated dogs to make blankets; and it has painted an increasingly detailed portrait of the intricate resource management these nations oversaw for millennia, even as changing sea levels reshaped the landscape.

This summer, the students and professors on Kakmakimiłh uncovered a geoduck shell, the first ever found in a shell midden, or mound of discarded shellfish. According to Canadian courts, this type of clam could only be harvested using modern equipment, so the Tseshaht have not had the legal right to commercially harvest it. But if the Tseshaht prove that geoducks were a source of food during an earlier time, they could gain that right.

“We had a name for geoduck and we obviously obtained it somehow,” Watts says. “When I sit here and think about all the flora and fauna we accumulated, it makes me think about the abundance of seafood we used to have. Now you hear these things about climate change and mismanagement, and we always managed it and were sustainable. We should be in the driver seat of our own land.”

On a misty morning at the old village of C̓išaa, Denis St. Claire stands at the top of a grassy midden, just beyond a carved statue of Naasiya’atu that greets occasional visitors. For field school students who have been working on Kakmakimiłh, this is the one day they don’t have to do any excavations. It’s a day for storytelling—beginning with the Tseshaht origin story.

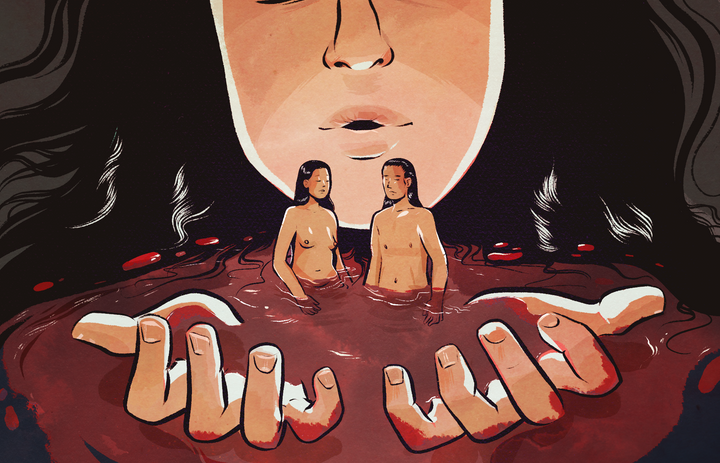

“Kwatyaat was the creator of the world we can see around us. He had a son called Kapkimyis, and in this story Kapkimyis is here with a shaman. Standing here, they cut with a mussel shell knife the thigh of Kapkimyis. The blood was scooped up and blown into. One version says the first woman emerges, the other says the first man. Whichever was created first, on the other thigh the same was done and out came the other gender. And the man was Naasiya’atu and the woman was Naasayilhim.

“As time goes on, their relationship is not always above reproach. They bickered, they argued. And Kapkimyis was getting a little pissed off and so he cautioned them. But that had become the definition of their relationship, so the behavior continued despite his admonishments.

“Kapkimyis had created them a river, and in a little bit of temper he destroyed the river as punishment. The banks all crumbled up and clumps of bedrock and trees and sand floated around in the water until they became fixed in position. And those clumps of river banks are the Broken Group Islands.”

When St. Claire comes to the end of the tale, he opens a discussion. “Stories have many purposes,” he says. “So why have such a story and pass it on generation after generation?”

Students offer a few answers, and St. Claire directs them to others. This particular story teaches a lesson about consequences, and helps the Tseshaht reflect on their roots. But it also has to do with resource management. “To be successful you need cooperation, not bickering and divisiveness,” St. Claire says. Out here on the edge of the continent, communities had to develop rules and norms about hunting and foraging and mussel collecting; they had to rely on each other for survival.

Ken Watts rarely comes out to the islands anymore. Fuel is expensive, and there are so many community members who have never had the opportunity to make the trip. He counts himself lucky for the two summers he spent at C̓išaa, and is enthusiastic about how the field work has continued to benefit the Tseshaht First Nation. “I hope we can always do this every year, for as long as I’m alive,” he says. “To show our history—the things we ate, the things we made, the things we did.” He wants his people’s history to be remembered so that his kids and grandkids know who they are, and where they came from. And archaeology, he says, is a big part of that.

Reporting for this story was supported by a grant from the Institute for Journalism and Natural Resources.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook