The Centuries-Old Fish Ladder That Feeds Maine’s Lobster Industry

Each spring, more than one million alewives navigate to the fresh water of Damariscotta Lake—with a little help

Straddling the border of Nobleboro and Newcastle near the Maine coast, the Damariscotta Mills fish ladder is an unexpected local landmark—a centuries-old effort to protect the alewives that travel each spring from Great Salt Bay to the fresh water of Damariscotta Lake, where the fish spawn, that is still an economic engine for the small towns today.

This story began with the alewife, an anadromous—or migrating from the sea to rivers to spawn—species of herring slightly larger than a human hand. The salty, bony fish was a dietary staple of the region’s Indigenous Algonquian people, who used nets to catch the alewives during the spring migration. The tribe even named the area Damariscotta, “place of an abundance of alewives.”

But by 1729, sawmills were under construction in the region to process the white pine trees needed to build ships for the British Royal Navy. One double sawmill, in particular, built and operated by William Vaughan, stood at the head of the falls between Damariscotta River and Damariscotta Lake, blocking the alewife corridor. The effect on the fish population was so drastic that the Massachusetts legislature (the region that is now Maine was part of Massachusetts until 1820) required the towns to build a fish ladder as a remedy. Nobleboro and Newcastle collaborated to build the structure—as they still do to maintain it—and the ladder was unveiled nearly 80 years later as the centerpiece of Damariscotta Mills.

The original ladder was a series of small pools connected by short passages that rise uphill to the lake and it worked marvelously—for about 180 years, with constant maintenance. But its stonework and the underlying concrete deteriorated as icy Maine winters dislodged stones, blocking the path and making the water so shallow that fish suffocated. By the 1990s, the fish ladder was on the edge of collapse, and fish count plummeted to less than 200,000.

“We were not getting fish up the ladder, and those that were getting up were exhausted, so we’re not sure if they were even spawning,” says archeologist and ladder project manager Deb Wilson. “And the ladder is not just used for alewives. Catadromous eels come up in spring to live in fresh water, smelts spawn in the lower ladder. It’s a busy place.”

Wilson and her husband, municipal fish agent Mark Becker, spearheaded the ladder’s restoration, a decade-long effort that included fundraising approximately $1 million. Working alongside them were community members, municipal and state experts, including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, to design and construct a modern fishway with a design similar to that of the original, consisting of a series of 69 ascending pools connected by weirs, or short waterfall passageways that each rise eight to 10 inches.

The work was restricted to November through April, Wilson says, because the fish take their time descending the lake after spawning and are active into the fall. She recalls the grueling winter scheduling to accommodate this aquatic timetable, including heated shelters so the concrete could cure properly, concrete pump trucks with crane booms reaching over private homes to pour the pools, and dismantling old residential walls to harvest original stones.

“Every year the ladder had to be ready to be used by the fish by April 15. There could not be a time when we blew it,” Wilson says. “It was very important to us to retain the character of the original fish ladder. All the stones from the original ladder were used.”

Completed in 2017, the renovated ladder, a serpentine shape shaded by mature trees, now ushers more than one million alewives to their natal waters. It winds 1,500 feet up the hill, rising 42 vertical feet from top to bottom. As water cascades downstream, fish leap up through weirs, then rest in a pool, and repeat the process until they reach the lake.

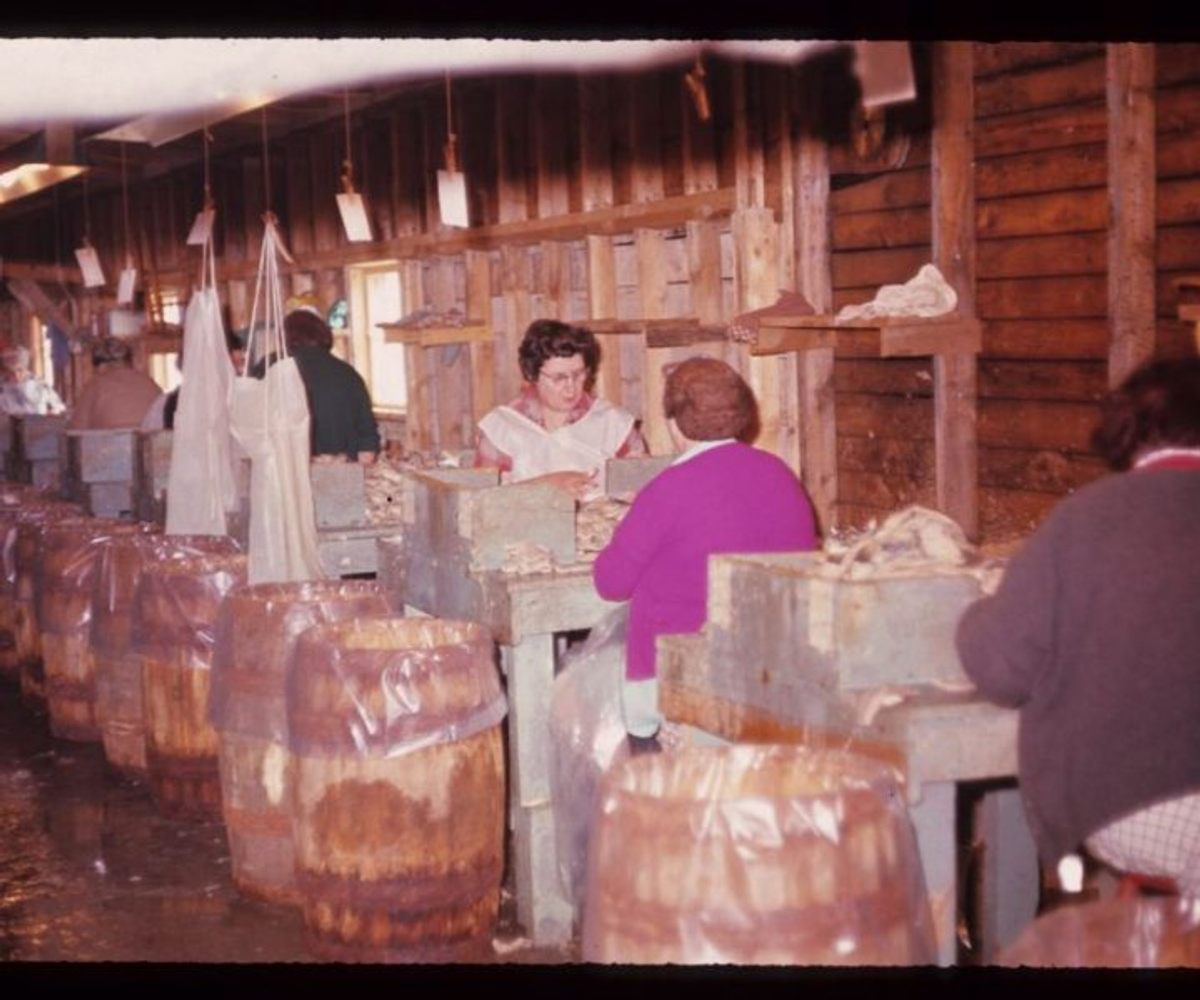

When they begin at the bottom, fish have to instinctively know which way to turn, however. Between 200,000 to 500,000 alewives go the wrong way and end up in the harvester instead. This traditional machine at the ladder’s base is a giant steel contraption that scoops errant fish into a holding pen and ushers them along a raised conveyor belt to waiting lobstermen. Volunteers wearing rubber waders manually load alewives in an age-old practice that has changed little since the 19th century.

“Getting fish into the lake is our number one priority. We’ll slow down the harvest if the fish numbers are low, because we want to ensure adult fish get up the ladder, and back downstream,” Becker says.

Historically, the harvested fish were salted or smoked at copious smokehouses nearby and were then packed in barrels and shipped overseas as a reliable and inexpensive food. The genesis of the state’s commercial lobstering industry in the 1840s prompted their demand as bait, and alewives’ value grew so much that there are now more than 30 alewife runs statewide.

“Lobstermen now come from the islands, down east, all over,” says Becker. “They arrive at night and sleep in their pickup to be the first in line. We also harvest for two co-ops that salt and freeze the fish, and restaurants experiment with them. Even using alewives as halibut bait has picked up steam.”

Some of the alewives are still reserved for the region’s widows. In 1839, Newcastle and Nobleboro voted that all widows would receive 400 alewives if they wished, says Nobleboro Historical Society President Mary Sheldon. Today, widows can apply to receive two bushels of the fish. Sheldon, whose husband passed away in 1999, claims her widow’s share each year, then exchanges them with a lobsterman for lobsters, because she admits the tradition’s historic charm outshines its effectiveness as a contemporary support mechanism.

“What do I need with two bushels of alewives?” Sheldon jokes. “They taste good if you like oily fish, and I do, but they’re a challenge because they have fine bones so it’s hard to get out the meat. Another Mainer told me to eat them with bread to push the bones down so I don’t choke.”

When the alewives are running May into mid-June, it is a traditional highlight for piscivores too. Seeking protein after a long, cold winter, birds including osprey, herons, eagles, and gulls prey on alewives, while seals lurk beneath the surface. This illustrates an ecosystem with an impressive balance, says Wilson, who watches from her home as the schools of fish surge up the river and into the base of the ladder.

Preserving the ladder was about saving more than the fish. “As a country, we don’t really have a culture the way the Native Americans did, and this ladder is so important to keep going so we can keep grounded. It gives us a sense of place. We are attached to the history, the land, the ecology, and it’s important to keep the flavor of Maine,” says ladder treasurer Laurel Ames. “We’re trying to be stewards of what they started in the 1700s.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook