For Many Islands, Tourism Means Too Much Trash. Is Cuba Next?

A busy street in Havana prepares to become somewhat busier. (Photo: Stefan Vetter/Flickr)

A busy street in Havana prepares to become somewhat busier. (Photo: Stefan Vetter/Flickr)

What will Cuba look like in 20 years? Right now, as the lifting of most remaining travel restrictions and embargoes seems increasingly imminent, people all over the hemisphere are betting on the answer to this question. Hotels and cruise ships are moving in. Other businesses are gingerly following. And Cuban citizens are gearing up for great things.

But some fear that Cuba’s future smells like something other than conviviality. With more business and more tourism comes their less nourishing trappings—lots and lots of garbage.

“There will be people touring the islands in volumes and numbers that Cuba has never seen,” explains Dr. Sarah Hill, an anthropologist who has been traveling to Cuba since 1982. “And they’re going to bring stuff that they don’t want to carry around with them for the entire trip, and so they’re going to leave it behind. And that alone will generate a waste stream that will be new to Cuba.”

This dry-up of goods also made Cuba a haven for classic cars. (Photo: Steven Rushing/Flickr)

This dry-up of goods also made Cuba a haven for classic cars. (Photo: Steven Rushing/Flickr)

Twenty years ago, Cuba was technically filled with trash. But it was trash that didn’t look like trash. Thanks to various trade embargoes and the fall of the Soviet Union, Cuba in the 1990s was essentially a closed system, cut off from most of the world’s goods. “There was nothing new to replace anything that you used up or broke,” says Hill, who studies “what people do with stuff they don’t want.”

So people made do with what they had, turning Coke cans into containers and dumps into public gardens. Hill knows people who became “artisanal plastic producers,” beach-combing for washed-up trash, melting it down, and pushing it through molding machines they had fashioned out of scavenged truck pistons.

Garbage is a problem that, from the outside, looks as straightforward as simple addition. More people + more goods = more trash. If there’s no way to get rid of the trash—say the place in question lacks infrastructure, or landfill space—that trash builds up. Cycle through over and over, and you’ve got quite a heap.

The subtraction that would let you cancel out that heap, though, is often not so simple. This is true especially if the people bringing the extra trash are vacationers, or refugees, or otherwise transient, because it becomes difficult for governments to build up the necessary waste management revenue through regular channels, like local taxes. This is why so many burgeoning tourist hotspots, quickly-developing cities, and places with porous borders end up with more trash than they can handle. Not everywhere can act like New York City and ship extra rubbish to Virginia.

Workers sort through trash on Thilafushi, the man-made trash island in the Maldives. (Photo: Shafui Hussain/Flickr)

Workers sort through trash on Thilafushi, the man-made trash island in the Maldives. (Photo: Shafui Hussain/Flickr)

At some level, Hill says, Cuban cities are already preparing. As credit card companies move in and entrepreneurs work to scale up wi-fi and other informal infrastructure, Santiago de Cuba, the country’s second largest city, has quietly been rolling out brand new trucks, installing dumpsters, and adding street-sweeping shifts.

But look at places that have faced similar changes, and these measures don’t seem like quite enough. Take, for example, the Maldives, where the government has decided to turn the 300 daily tons of tourist garbage into their own artificial trash island, called Thilafushi. Or Beirut, Lebanon, where a huge influx of Syrian refugees, combined with protests blocking the city’s overtaxed landfills and general municipal disarray, has filled the streets with “mounds of stewing garbage.” Mainlanders and ecotourists have given the Galapagos much more than it can handle, and there is so much trash in Bangalore, India, that some travelers, paradoxically, go there to see it.

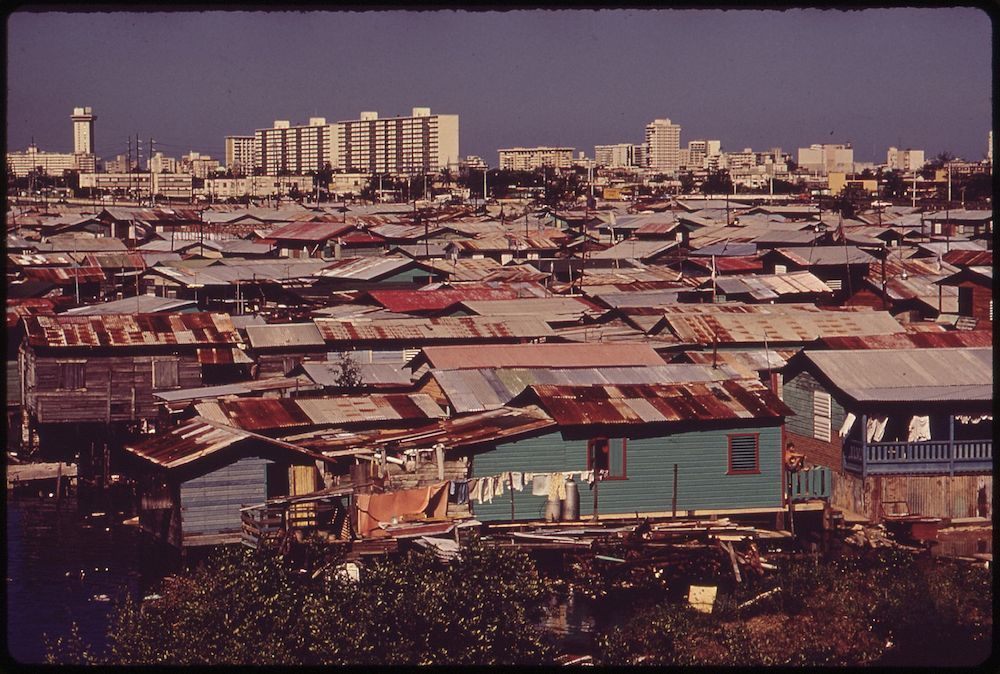

Trash doesn’t have to be forever, and in recent years, many relatively small places with relatively big trash problems have come up with ingenious, if arduous, solutions. Just look at Puerto Rico. After thousands of Puerto Ricans lost their homes in the 1928 Okeechobee Hurricane, officials directed them to the Martin Pena Canal, once a mangrove-bordered channel that flowed into the center of the capital city, San Juan. Swampland is a hard area to settle, so they filled it in the only way they could—with dirt, debris, and lots of garbage. The shantytowns they built on top grew steadily over the decades, and by 2010 the area housed about 30,000 people.

The Martin Pena Canal shantytown circa 1970, with San Juan rising in the distance. (Photo: John Vachon/NARA)

The Martin Pena Canal shantytown circa 1970, with San Juan rising in the distance. (Photo: John Vachon/NARA)

That many people meant even more trash. The heap grew up and out of the immediate swampland, and the channel, once 400 feet wide, shrank to a three-foot trickle. People started getting sick. When the garbage begun threatening the safety of entire estuary, people realized it was time to clean up Martin Pena Canal and rebuild on something more solid. Beginning in the 1970s, Puerto Ricans steadily drummed up local money and support to start the process; by the end of this year the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is slated to finish the job, and begin building bridges, sewers, and power lines.

This effort has taken decades. But sometimes, quick fixes are worse than no solutions at all. Oahu, Hawaii, the state’s most populous and popular island, found this out the hard way in 2009. Oahu is a tourist mecca, home to Honolulu and many of the state’s most pristine vistas. But it stays that way partially because Honolulu shunts all its trash off to the Leeward Coast, far from the common vacation spots. When the one landfill on the island filled up, officials accepted a private company’s offer to ship the extra trash up to Washington State.

There was just one problem: the private company didn’t have the necessary permits, and the residents of the Indian reservation in Seattle where they had planned to dump the trash made sure they never got them. Thus, bales of the trash ended up moldering in the yard of an industrial park on the island for nearly a year before the plan was abandoned. They were eventually incinerated in-state.

A “private landfill” in Santorini, Greece, another small island with a large trash problem. (Photo: Norbert Nagel/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

A “private landfill” in Santorini, Greece, another small island with a large trash problem. (Photo: Norbert Nagel/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

The best defense against this kind of issue is a good offense, and one of the best offenses in the world belongs to Taipei City. Taiwan is an island nation, and its capital used to be swamped with trash. In 1998, the country’s Environmental Protection Administration implemented a waste management program that seems draconian by mainland standards: residents must sort their junk, bag it in official, color-coded trash bags, and heave it onto the local garbage truck, which shows up five nights a week at a designated pickup spot.

It’s a complex system, and many a forum thread is dedicated to explaining its ins and outs to newcomers. It’s also efficient and effective—revenue from the special bags pays for the program, and Taipei City’s recycling rate has more than quintupled since it started. Devotees describe the nightly wait for the truck (which signals its arrival by jingling Beethoven’s “Fur Elise” at high volumes, like a demented ice cream van) as “one of Taiwan’s liveliest communal rites.” Most importantly, there’s way less garbage kicking around.

A singing garbage truck makes its nightly rounds in Taipei City. (Photo: Jin/Flickr)

A singing garbage truck makes its nightly rounds in Taipei City. (Photo: Jin/Flickr)

To those Cubans used to making household necessities out of flotsam, the ban’s lift still seems more like a promise than a threat. ”One friend told me that if the coming of the Americans means more garbage, then ‘let the city be covered in it,’” Hill writes.

But as things start ramping up, all involved parties would do well to be proactive and keep their noses peeled. After all, everything looks different from under the heap.

A Cuban street sweeper gets ready for the influx. (Photo: Diana Simmons/Flickr CC)

A Cuban street sweeper gets ready for the influx. (Photo: Diana Simmons/Flickr CC)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook