The Roman Museum With a Taste for Historical Cookbooks

A former pâtissier’s culinary collection is now available to the public.

Rome’s Circus Maximus, once the largest stadium in history, is now a massive green space: nondescript enough for dogs to defecate on, yet far too important to bulldoze. The city is stuffed with such examples of well-preserved but long-disused monuments that Romans have proudly built to uphold their culture and civilization as the world’s apex.

Of late, however, a growing community of Italians are turning to a more vivid way of honoring the past. Both restaurants and a museum are embracing new, experiential forms of food archeology to demonstrate how food has always been one of the glories of Rome.

On the northwestern flank of the Circus, an ancient marble finger mounted on a wall points to the sky above the entrance to Garum, Rome’s new culinary library and museum. Inside, amongst the creeping foliage and lush marble of a former monastery, I meet Matteo Ghirighini, the Museum’s director and lead curator.

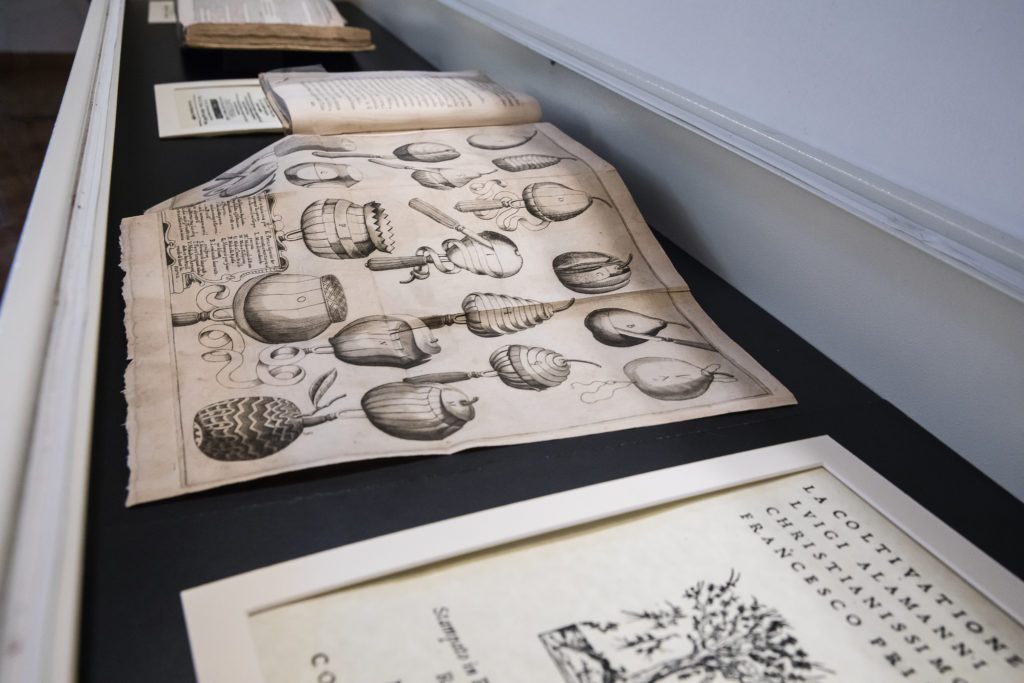

Despite only opening in February 2020—two weeks before the pandemic gripped the country—the space itself feels practically primordial. Ghirighini first walks me through the museum’s ground-floor collection of kitchenware, pointing out 17th-century cake molds and hand-painted terrine pots hailing from throughout the continent. These items, once common amongst the elite, are now quite rare.

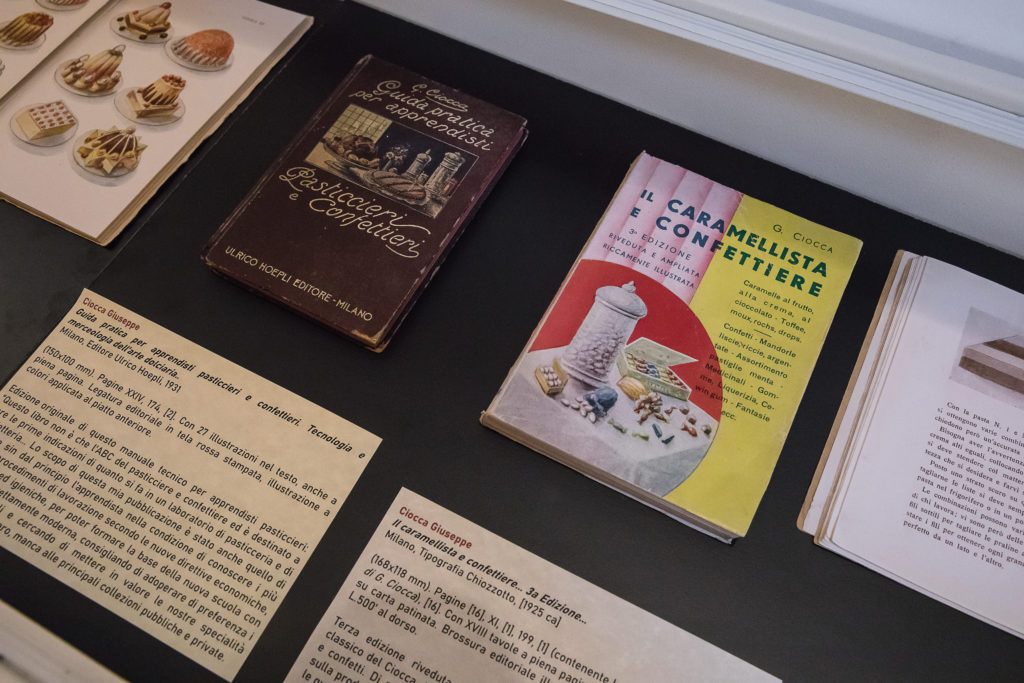

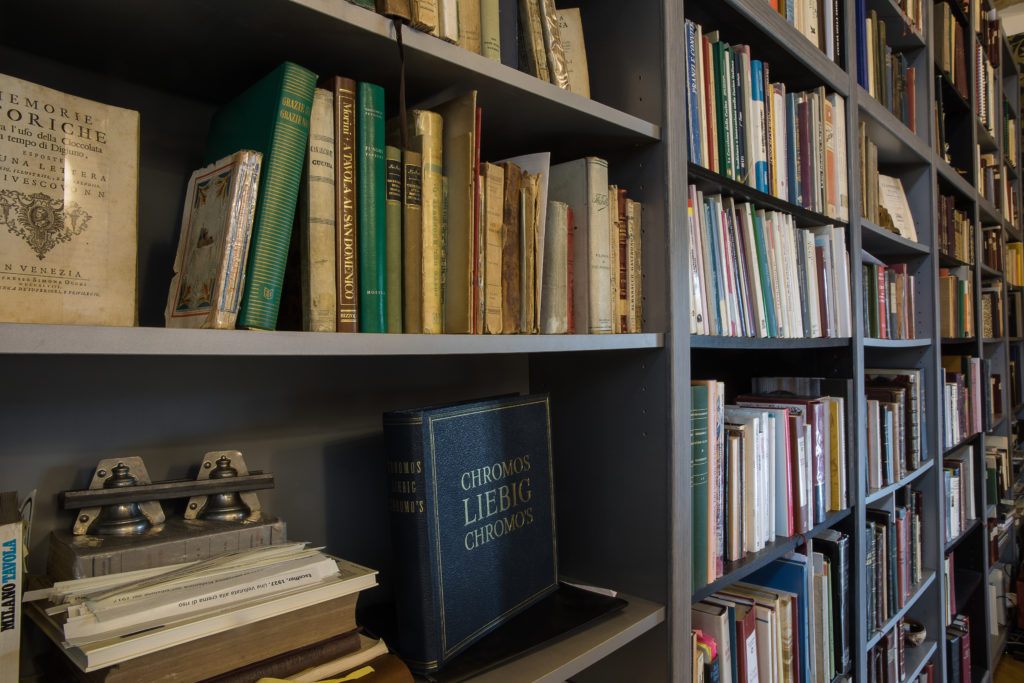

Such implements, though, are only half of Garum’s collection, the culmination of a lifelong obsession of hotelier-turned-pâtissier Rossano Boscolo. In the early 1980s, the pastry chef began accumulating these tools, later opening a cooking academy in the Etrurian town of Tuscania. It wasn’t long before Boscolo made the leap to historic culinary texts, compiling a collection that is at once comprehensive and eclectic. Finally, after nearly 40 years of amassing these treasures, Boscolo made his collection public, putting Ghirighini, an antiquarian bookseller by trade, at its helm.

By appointment but free of charge, visitors to Garum can access an invaluable selection of largely French and Italian cookbooks, stored in the upper level of the museum. From a 1541 Lyon imprint of Apicius’s chronicle of ancient Roman cuisine to a first printing of Bartolomeo Scappi’s Renaissance era cookbook, Boscolo’s collection spans millennia of gastronomic history.

Most of the books happen to be first editions, which are seldom accessible to the public. The collection is a resource for both historians and scholars, but Ghirighini also considers it a way for ordinary people to connect and empathize with cooks of centuries past. “The study of culinary texts,” Ghirighini tells me, “affords a rare insight into those who are doing the cooking, particularly amongst the working-class. In this way, we can better understand the spirit of their time.”

Where I’m eager to delve into the era of Apicius, whose first-century De Re Coquinaria is generally considered the first cookbook on record and whose true authorship remains forever in question, Ghirigini prefers to keep the museum’s focus on the Renaissance era and beyond. According to him, the ancient works are “unreliable.” He’s not wrong. Even the museum’s namesake garum—an ancient condiment made from fermented fish innards—lacks any sort of cohesive recipe to be faithfully replicated.

The notion of absolute authenticity plagues any scholar focused on the ancients. Instead, Ghirighini sees the museum as sort of a gastronomic Mythbusters. With Boscolo’s collection as a resource, the museum tracks the evolution of famed dishes, looking to separate food fact from folklore while engaging as broad an audience as possible.

During its short existence the museum has hosted a diverse range of exhibits and initiatives, including “Garum By Night,” an evening of historical fine dining, the “Panettone Maximo” competition where local bakers vied to create the best Christmas cake, and wine tastings. Boscolo himself has also hosted a limited-run television series entitled Il gusto di sapere (“The Pleasure of Knowledge”) in which he and a celebrity co-chef cooked recipes sourced from his book collection, cooking them onsite while discussing their origins.

This scholarly attitude towards food has spread to a number of innovative restaurants in Rome. Hostaria Antica Roma’s Paolo Magnanimi knows quite well the limitations of the texts he’s researched. Consider Magnanimi’s version of patina cotidiana, translated literally to “everyday dish.” Magnanimi uses era-appropriate ingredients—beef, fennel, and cheese—to produce a kind of proto-lasagna.

Yet consulting Joseph Dommers Vehling’s translation of Apicius, one won’t find a cheesy casserole. Rather, the first mention of patina quotidiana features cow’s brains mashed, poached, and presented as a sort of omelet. Later in the Coquinaria, though, the patina cotidiana does feature varied ingredients, such as cow’s udder and fish, sandwiched between laganum, a sort of flatbread made from wheat flour. As several culinary scholars have hypothesized, the recipe may well have served as precedent for the sheets of lasagne first referenced in the 14th-century Liber de Coquina.

By presenting the patina as a tomatoless lasagna, Magnanimi can in theory cater to modern appetites while also showing how much Italian food has changed over the centuries. After all, tomatoes didn’t exist in Europe until the 16th century.

Operating in clear view of the Pantheon, the oldest operational building on earth, Rome’s Armando al Pantheon may well be equally iconic in certain circles. Founded in 1961 as a traditional trattoria by its namesake, only under the stewardship of Armando’s son, Claudio Gargioli, has the trattoria blossomed into a proper ristorante.

Here, Apicius’s recipe for duck is simply prepared with prunes and an ancient honey wine called mulsum, while his guinea fowl, for lack of laser—an ancient herb lost to time—is enhanced instead with porcini mushrooms and dark ale. Like Magnanimi, Gargioli weaves narrative and history into his dishes, even publishing a literary cookbook that ties personal anecdotes to traditional recipes.

Magnanimi himself happens to be meeting up with Ghirihini the day after our call, hinting at future collaborations between his restaurant and the museum. Pandemic permitting, Ghirighini envisions visiting chefs and scholars perusing Garum’s rare texts and illuminating them through tastings and even more events within the library. The reanimation of historical cuisine affords a rare opportunity to engage with and learn from history, as cooks interpret old recipes to the best of their abilities. As Magnanimi and Gargioli have shown, the attempts may not be absolutely authentic, but they’re almost always delicious.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook