The Curious Rise of Historic Trolley Tours

How did these nostalgic vehicles become fixtures in cities across America?

John Buchna, head of the Downtown Erie Business Improvement District in Pennsylvania, considers his city’s trolley service a huge success. Established in 2006, it runs in a loop downtown Thursday through Sunday, shuttling tourists and residents to Erie’s main attractions. The trolley, he says, is “a tremendous asset,” for drawing both tourists and suburbanites into the city.

By trolley, though, he doesn’t mean trolley exactly—at least not in the technical sense of the word. This trolley has rubber wheels and runs on pavement. Some might call it a bus. But with arched windows, brown, wood-like panelling, and a brightly painted body, it’s designed to emphatically reject that label.

Erie isn’t alone in its affinity for these types of vehicles; buses dressed-up as century-old trolley cars have become a staple of American cities. Whether exclusively serving tourists or functioning as part of a public transit system, they can be found in cities as geographically diverse as Miami, Florida and Juneau, Alaska.

Yet despite their prevalence, no cities or companies lay definitive claim to the trend. Some point to San Francisco’s iconic (real) trolley cars as inspiration; others just point to a neighboring city that got a trolley route a few years earlier.

So where did these “trolley-replica buses” (as they’re sometimes called) come from? I posed the question to an official at the American Public Transit Association.

“I’ve worked here 14 years,” she said. “You’re the only person who’s ever asked me about them.”

One of the earliest and most influential adopters of these vehicles was Chris Belland, CEO of multi-city sightseeing company Historic Tours of America. In the 1970s, before becoming “the king of trolley tours,” as one trolley-industry insider described him, Belland was living in Key West, the southernmost point of Florida, and a city that’s currently recovering from Hurricane Irma, which hit it in early September. There he was buying and restoring historic properties, and giving tours of the island’s downtown. And downtown Key West, it turns out, was a ripe breeding ground for trolley mania.

“In the 1970s Key West was a down-and-out city,” Belland says. A large portion of the Navy Base that anchored the island’s economy closed in 1974. After that, tourism was seen as crucial to the area’s survival.

One long-standing attraction on the island was the “Conch Tour Train.” This rubber-wheeled amusement-park-like ride that had been giving guided tours of Key West since 1958. The miniature train played into the provincial, far-from-the-mainland vibe that the Florida Keys had long cultivated and used to attract visitors.

And like any successful enterprise, it had a budget-friendly competitor: “The Conch Town Trolley.”

“[The Conch Town Trolley] used cut-down bread trucks that pulled a boat trailer, with plywood on the top and park benches bolted down for seats,” says Belland. “It was a very, uh, homemade type of tram.”

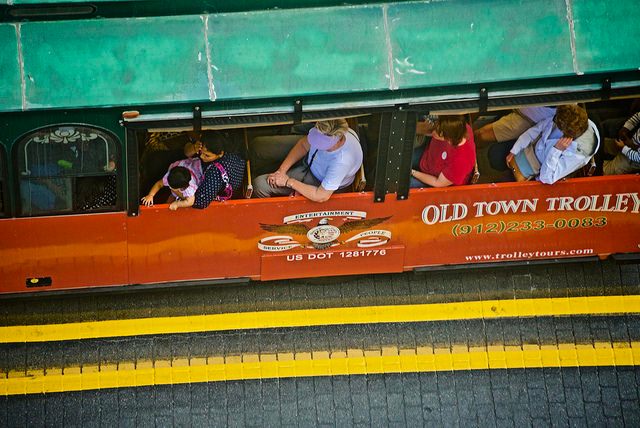

Belland and his business partners bought The Conch Town Trolley in the mid 1970s, which by then (after being sued by the Conch Tour Train for having too similar a name), was renamed the Old Town Trolley. They began to experiment with different types of vehicles and tours, looking for ways to stand out from their more popular and entrenched competitor.

One night in 1979, Belland found the vehicle he was looking for.

“I was up in Miami—I saw a [replica] trolley in the Orange Bowl Parade and I said, ‘Boy, that would be just the thing to compete with the Conch Tour Train!’ Because it has the same thematic value, and played into the town’s history.”

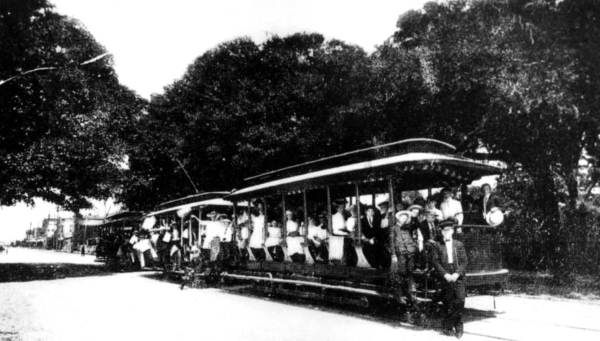

Key West—like so many other cities in America—once had streetcar lines. Streetcars were a defining piece of urban infrastructure in the pre-automobile era, and one that, by the 1970s, existed in only a handful of cities and towns. Trolley replica buses recalled those streetcars, and Belland had a hunch that evoking this history would work in their favor. They bought six “themed vehicle trolleys,” and started giving tours of Key West in 1980. That year they drew 77,000 riders.

The numbers only grew. And little did visitors on Old Town Trolley know, soon these vehicles would be coming to a city near them.

Today Belland’s idea to “play into the town’s history” as a way of drawing tourists may seem obvious. But when Old Town Trolley bought those vehicles in 1979, that idea was just entering the mainstream. In fact, it was almost a reversal of how many people viewed urban tourism in the decades prior.

“In the 1950s and 60s, you had urban renewal projects tearing down historic city centers, and urban disinvestment, with the thought that the city would be remade with a new image,” says Phil Gruen, Associate Professor of Architecture at Washington State University School of Design + Construction. In these decades older buildings and neighborhoods were often ignored and shunned by governments and developers. Large-scale projects like Government Center in Boston and Penn Center in Philadelphia came to epitomize dominant design trends of the era, wherein older buildings and neighborhoods were demolished and replaced with a Modernist-inspired combination of government buildings, high-rise housing, and office space. Highways were key to this strategy as well, as planners and designers sought to create a streamlined, car-centric city of the future.

Genuine trolleys and streetcars had no place in this brave new world.

But in the ‘60s and ‘70s, tastes in urban design and development began to shift. Developers started to find value in recalling the look and feel of cities of the 19th century. Urban forms that had been viewed as obsolete and inefficient in the ‘50s and ‘60s (crooked streets, cobblestones, pedestrian-centered neighborhoods) came to be viewed as quaint—nostalgic, even. Historic city centers were suddenly seen not as places to demolish or ignore, but to celebrate. And profit from.

Belland’s company, Old Town Trolley Tours, rode this wave of nostalgia—what better way to transport tourists through spiffed-up historic neighborhoods than in a modern recreation of a historic streetcar?

Throughout the ‘80s, demand for these anachronistic vehicles grew across the country. Companies like Chance Manufacturing, an amusement ride manufacturer based in Kansas, expanded their operations to include building high-quality bus/trolley hybrids.

But it wasn’t just the streetcars that made Belland’s tours stand out.

“We made a ‘continuous loop tour’ [in Key West]—now known as a ‘hop-on-hop-off’ trolley concept.” Belland says. “Everybody’s doing ‘hop-on-hop-off’ now—I’m pretty sure we were the first.”

Kitschy-looking trolley replicas shuttling tourists on a hop-on, hop-off tour route proved a winning model. Old Town Trolley spread. First to Boston, where they bought up a similar trolley tour company, and then onto cities across the country. Today the company—now called Historic Tours of America—operates in six cities around the United States, and carries about 3 million passengers annually. Belland even trademarked a word to describe the experience the company provides: “transportainment.”

“If you see anybody using it, let me know,” he says with a laugh.

In the last few decades, these vehicles have further embedded themselves in American urban life, as municipal governments hopped on board the trend, too.

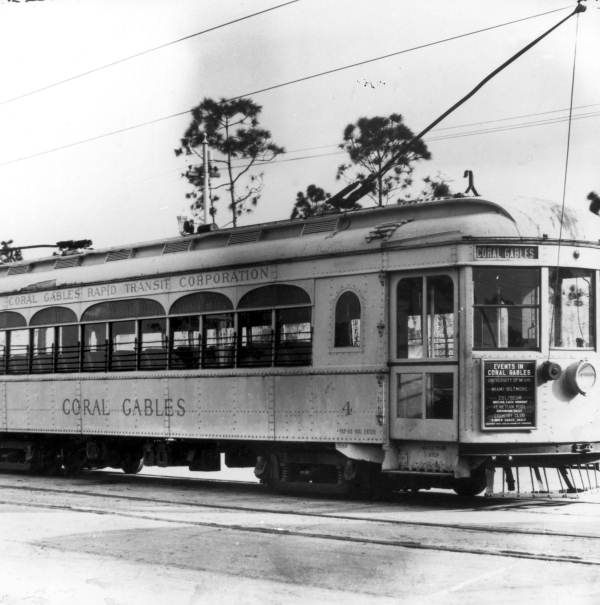

William Kyrdeck Jr., former vice-mayor of Coral Gables, Florida, described how his city came to include trolley replica buses in its public transit system. In the late ‘90s Coral Gables—an affluent city right next to Miami—began exploring new transit options to help connect its historic center to Miami Dade’s mass transit system. After hiring consultants and surveying residents, they decided on a slightly unorthodox option.

“We like the small-town feel [of Coral Gables], and the trolley kind of helps support that,” he says. It’s not like getting on a big bus, it’s like getting on a…little trolley.”

The “little trolleys” were a big hit—they surpassed all their ridership expectations the first year of operation, and currently serve around 1.25 million riders per year.

Erie, Pennsylvania launched its weekend downtown loop trolley service in 2006. It’s a “great visual tool,” says John Buchna. “By giving a more historical look to it, it’s more approachable to tourists. [You] step onto it knowing you’re going to be taken on a tour. You know you aren’t going to get on the wrong route.”

Asked about the origins of these trolleys, Buchna summed up the feelings of many: “I don’t know who invented them, but I’m sure glad they did.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook