In June 1950, protesting bartenders descended on New York’s Fifth Avenue and called for an end to the Moscow Mule. That, at least, was the story the late drinks salesman John Martin told the Hartford Times in 1964. “They had a big banner that read, ‘Down with the Moscow Mule—We Don’t Need Smirnoff Vodka,’” Martin said. “It made page one of the New York Daily News, the whole page. Our people came rushing in to me. ‘What are we going to do about this,’ they wanted to know. Do! It was great. All the people who saw the sign were rushing into the bars to try the drink.”

At the time of the march, vodka was increasingly popular. Until the 1930s and 40s, it had been strange, foreign, and little known. Gin was the white spirit of choice for Americans, and vodka was a foreign interloper. But by 1950, the drink was trending, and front-page news of a vodka cocktail would have been a coup.

There’s likely only a grain of truth to Martin’s tale, though. There were anti-Russia protests in New York in 1950, but there aren’t records of any in June. And a search through the New York Daily News archives reveals no such front page. But this kind of narrative—highly repeatable, memorable, sellable—was characteristic of Martin, a canny salesperson without whom vodka would likely never have conquered the American market.

But it started long before that—a first falling domino, some 20 years before American drinkers embraced the spirit, was the Russian Revolution. Before it, Smirnoff vodka, known locally as Smirnov, was among the uppermost of top-shelf brands, and the preferred drink of the court of Czar Alexander III. But it was a poor credential for a socialist revolution, and the only member of the Smirnov family to escape Moscow was Vladimir Smirnov. In France, he struggled to sell vodka in a land of wine and cognac. Then, in 1925, the destitute Smirnov met Rudolph P. Kunett, born Kunettchenskiy, a young distiller who fled the revolution to America. For 54,000 francs—around $50,000 in today’s money—he sold Kunett the exclusive rights to make and sell Smirnoff vodka in the United States and Canada.

Perhaps Kunett believed that Prohibition was on its way out, and this investment was therefore a foolproof plan. Instead, it continued for another nine years, putting the kibosh on any swift financial gains. In March 1934, after the ban on booze had been lifted, Kunett opened the country’s first domestic vodka distillery, in Bethel, Connecticut, and waited for the cash to roll in as the bottles rolled out. He would be waiting a while. Americans did not drink vodka, and the ritzy Smirnoff name was meaningless to prospective drinkers. After a 13-year-ban, Americans seemed more interested in old favorites such as whiskey, gin, and beer. In his first year, Kunett sold just 1,200 cases, many of which went to Russian and Polish migrants living in the area.

Eventually, Kunett went bankrupt. In 1938, he attempted to sell the business for $50,000 to food and drinks distributor G. F. Heublein & Bros. They didn’t have $50,000—but they did have the $14,000 (around $250,000 in today’s money) to buy his equipment. John Martin offered him a deal: He would buy the rights and Kunett’s equipment, give him a job, and offer him and his stockholders five percent of royalties on every Smirnoff bottle sold for the next decade. (Kunett anticipated that these royalties would come to nothing.) Heublein was hardly thriving—only their A1 Steak Sauce had kept them running throughout Prohibition—but this was an investment they could afford.

At first, sales stayed flat. It’s not hard to imagine why. Vodka is pure grain alcohol mixed with water and filtered through charcoal. It is a literally a neutral spirit, with any character-giving oils or compounds stripped out. The resulting flavor may be sterile, even antiseptic, which is a tough sales pitch, especially if you’re encouraging people to drink it on its own. But if Heublein could make it work, the ease and relative inexpense of producing the spirit would spell healthy profit margins.

Then, Martin noticed an unusual uptick of sales in Columbia, South Carolina, where a distributor ordered 10 cases, then 50, and finally 500.

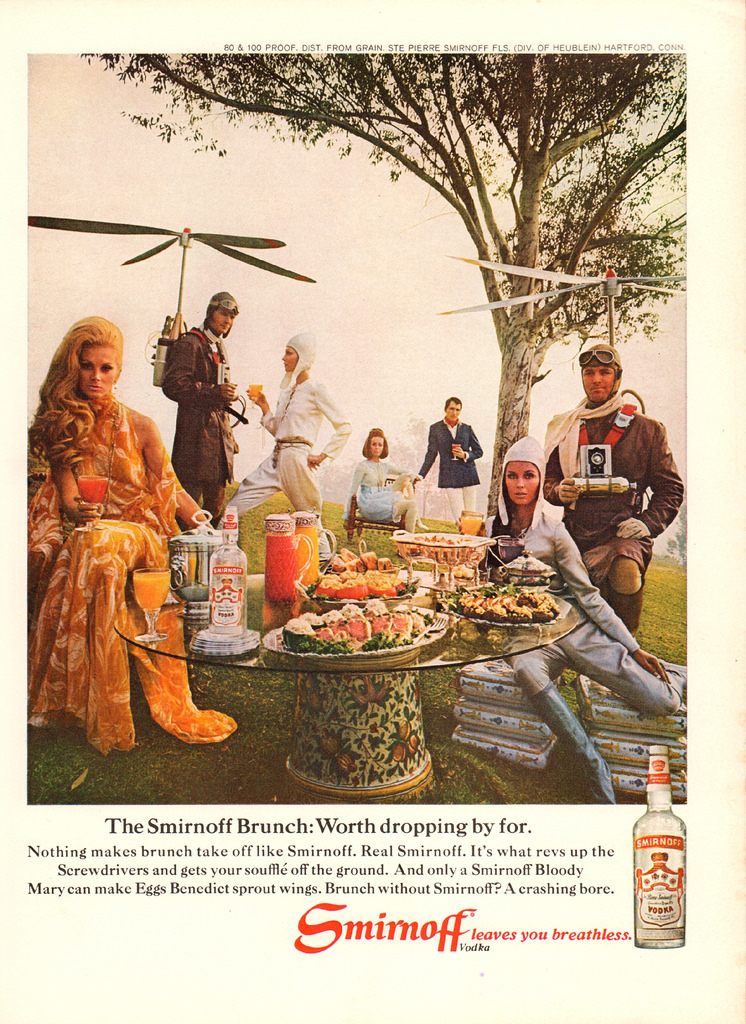

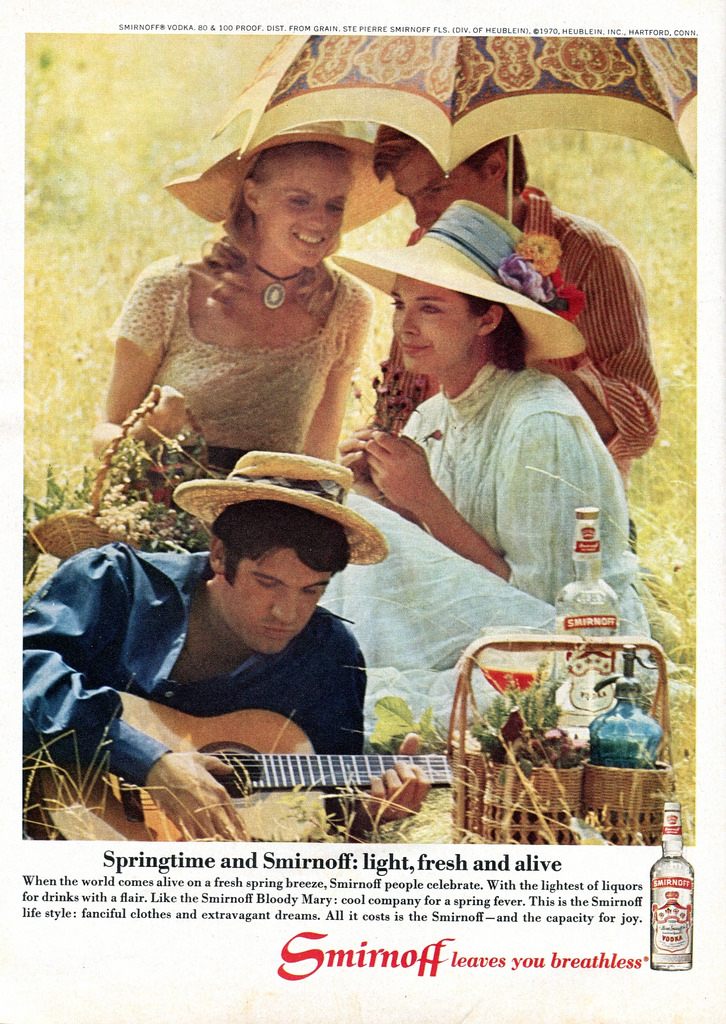

What had happened was a curious fusion of advertising savvy and plain luck. Heublein had, according to its own lore, bottled the vodka even before they had the right caps for it. Tops were labeled “whiskey” instead of “vodka.” The South Carolina distributor, Martin told the Hartford Times, had capitalized on this mix-up with a streamer that read: “Smirnoff White Whiskey—No Smell, No Taste.” “It was strictly illegal, of course, but it was going great,” he said. “People were mixing it with milk and orange juice and whatnot.” Perhaps Smirnoff couldn’t celebrate its flavor, but it could boast about its lack thereof. While whiskey hovered on your breath, vodka left no trace, which eventually inspired the “Smirnoff Leaves You Breathless” campaign.

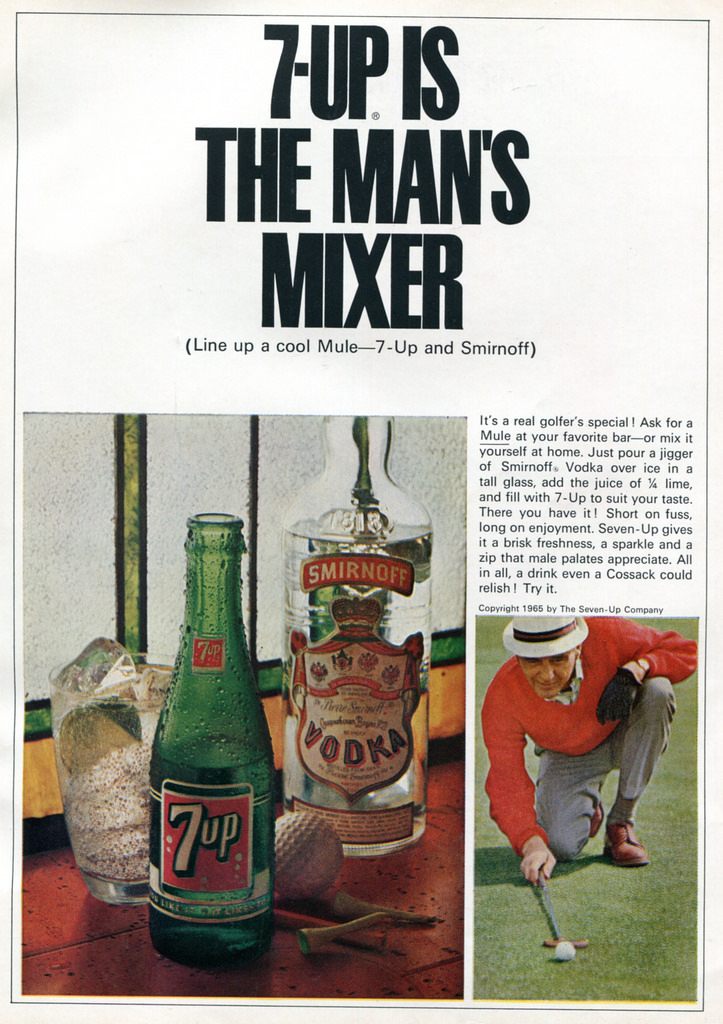

Americans liked to drink brown spirits straight, but thought of white ones, such as gin, primarily as drinks to be mixed. Cocktails were becoming popular, and vodka proved a useful inclusion. The Screwdriver mixed orange juice and vodka, the Bloody Mary tomato juice and vodka, the Ice Pick iced tea and vodka. The Bull Shot, now all but forgotten, involved warmed, spiced beef broth and vodka.

Most important of all was the Moscow Mule, which Martin and Kunett dreamed up. The drink first made an appearance in a Los Angeles restaurant called the Cock’n Bull in 1940. The owner, Jack Morgan, had a great deal of homemade ginger beer he was trying to shift (Americans preferred ginger ale). His girlfriend, Ozeline Schmidt, who Martin described as a “great, big, beautiful, buxom woman,” was the heiress of a copper factory struggling to sell its products. Kunett, now Smirnoff’s Advertising Manager, met with Morgan, Martin, and Schmidt to create a drink that combined ginger beer and Smirnoff vodka. In the Moscow Mule, a copyrighted drink, these were mixed together with lime juice and served with a squeeze of lime in a copper mug.

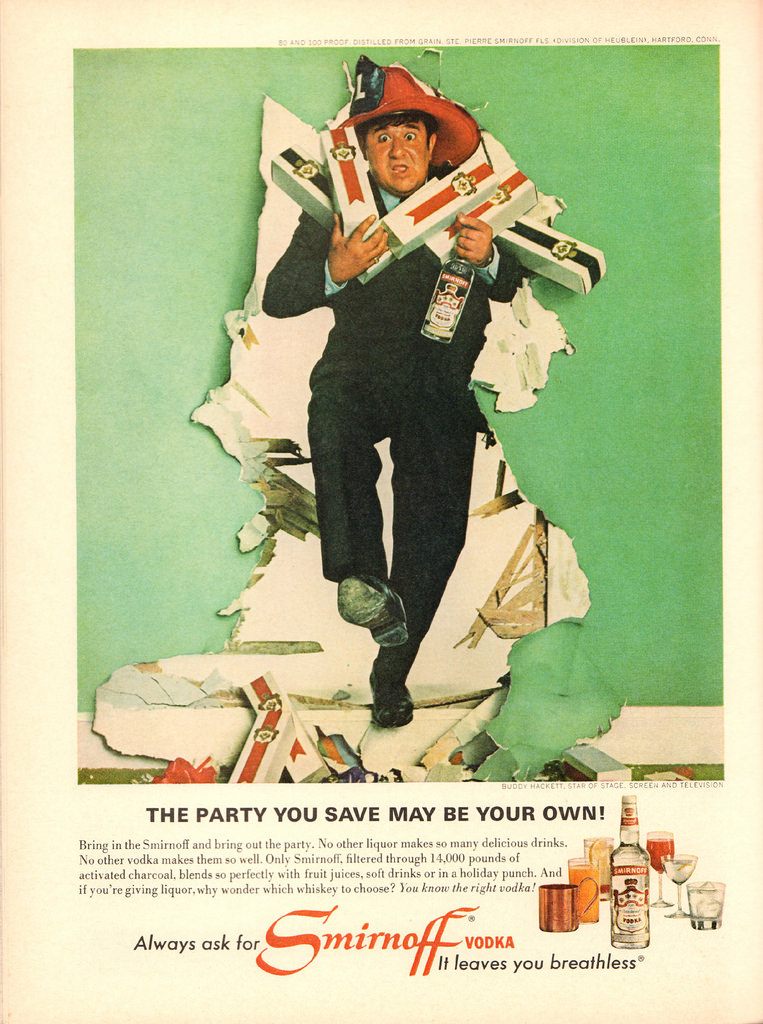

Throughout the Second World War, Heublein stopped producing Smirnoff. Then, in 1946, with Martin at the helm, they began aggressively promoting the cocktail, supplying bars across the country with Moscow Mule signage and instruction. At first, bartender after bartender refused to try it, Martin said. ‘“He’d say, “What, drink that stuff? Russian dynamite? And then drop dead? No, sir!’” So Martin concocted a scheme involving recently-invented Polaroid cameras.

He would make them a Moscow Mule, and then, if the barkeep tried it, take and print a photo of him drinking it out of a copper cup. “He would reluctantly sip a Moscow Mule, and he’d say, ‘Tastes pretty good.’” Martin would take two photos—one for the bartender’s wife, and the other to take to the bar across the street.

The cocktail became famous across America. “The drink has caught on rapidly,” the New York Times reported in 1954, “and is now firmly entrenched.” Americans weren’t drinking significantly more alcohol—national liquor consumption increased by about six percent in 1953—but they were drinking much, much more vodka. Production rose 47 percent, and the Moscow Mule was a major factor.

Vodka also benefited from its popularity in Hollywood, where, in an effort to maintain a squeaky-clean reputation, alcohol was banned in many contracts. An “It Takes Your Breath Away” slogan sold especially well to people who did not want to be caught drinking on or off the job. The connection helped glamorize vodka—at a party thrown by Joan Crawford, in 1947, only vodka and champagne were served. Smirnoff continued to dominate the market, making up 99.5 percent of domestic production until the 1970s. Given that only around half a percent of vodka drunk in the United States was imported, Smirnoff was the only vodka most Americans knew.

A potentially challenge, however, was the Cold War, which incited anti-Russian sentiment. Protests were common, and the New York Daily News, even if it didn’t have that fabled barman’s banner on the front page, often featured stories about teetotaling groups upset about Russian drinks. To counteract this, advertisers stressed the Imperial Russian connection over Red Russian connotations. Smirnoff’s advertising campaigns featured British or American celebrities—most James Bond films after 1962 showed the avowed enemy of Soviet Russia ordering vodka martinis. It was a global drink, not a Russian one, and even the most patriotic of Americans had nothing to worry about.

By the 1970s, vodka was entrenched in American drinking habits, selling 80.3 million gallons in 1975. Over the following decades, its popularity would rise (thanks to the famous Absolut advertising campaign designed by Andy Warhol) and fall (as craft cocktails became more popular) and rise once again (with club kids swigging vodka and Red Bulls). It’s now the highest-selling spirit in the United States.

Late in his life, Martin would say he had no idea precisely what had inspired him to invest in that tiny Connecticut distillery. But by doing so, he changed American drinking and nightlife. “It was all luck, or hunch, or whatever you want to call it. We owe it entirely to good fortune,” he said. “Not to any great genius.” The truth was likely a cocktail of the two.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook