How the Oxford English Dictionary Went from Murderer’s Pet Project to Internet Lexicon

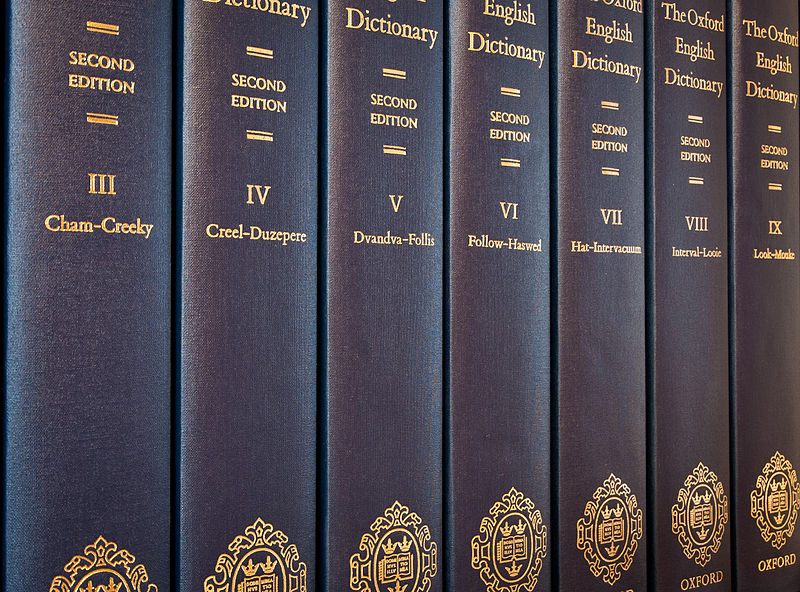

A 1989 edition of the Oxford English Dictionary, which contains 59 million words. (Photo: Cofrin Library/flickr)

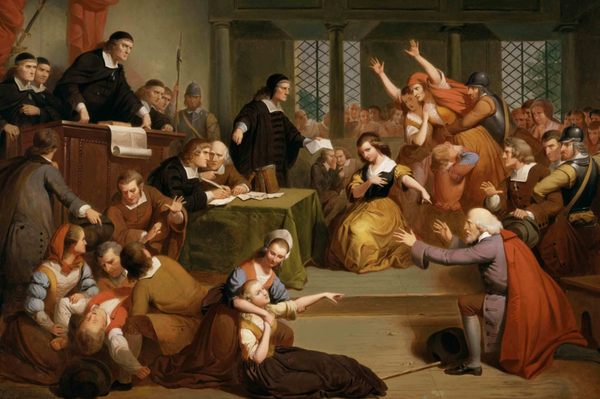

A shot rang out into the cold night air in Lambeth Marsh, a notorious London slum. Police officers rushed to the scene. There, they found a well-dressed surgeon, Dr. William Chester Minor, who quickly admitted to committing a murder. While the body of a local man named George Merrit lay lifelessly on the ground, the doctor attempted to explain his motives.

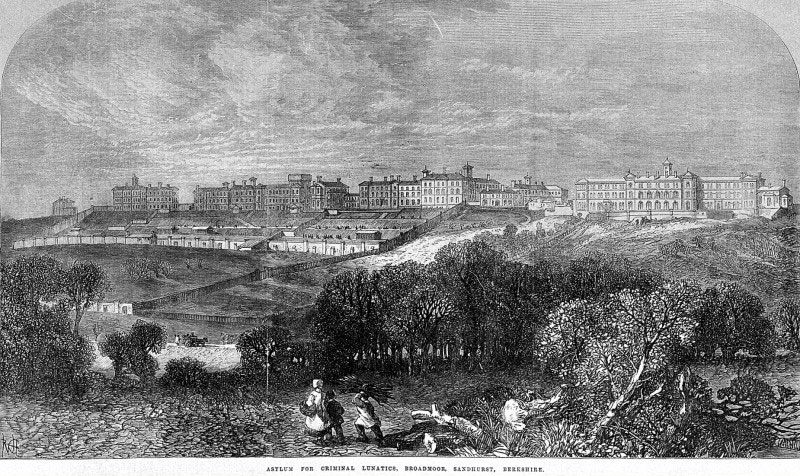

He claimed he meant to shoot somebody else—who was part of a broad network of Irish avengers that were out to get him. After his unhinged confession, Minor was admitted to the Broadmoor Insane Asylum in 1872. He lived there for decades, reading books, painting watercolors, and contributing to the most comprehensive English language dictionary in existence, the Oxford English Dictionary (OED).

Broadmoor Asylum in 1867. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

It seems unlikely that a murder in the slums of London would be connected to the preeminent English dictionary of our time, but it is. And perhaps just as amazing is the continued life and evolution of the dictionary itself. This month, the first batches of new words selected for OED inclusion in 2016 will come out, and will no doubt be the source of much conversation, online and off.

“The internet has simply accelerated, and globalized, a dynamic that was almost exactly the same in Shakespeare’s day,” says Robert McCrum, co-author of the book and TV series, The Story of English.

Just as it was in the beginning, choosing the “official” definitions of a living language is a fraught, confusing, and incredibly human process.

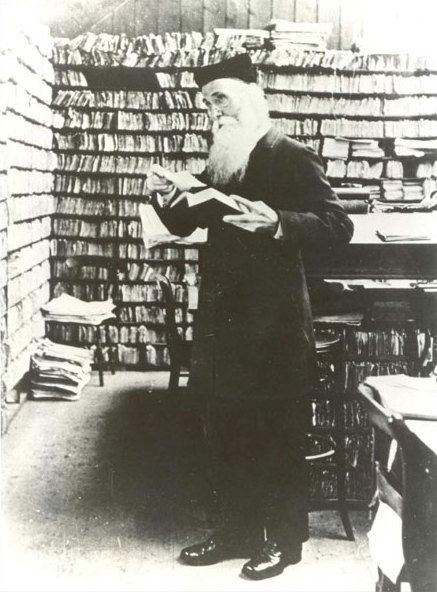

In 1879, Minor began to submit thousands of words to the Oxford English Dictionary via a mail-in volunteer system to the dictionary’s editor, Dr. James Murray. Each day, Murray sifted through thousands of paper slips, which volunteers mailed in after reading books he sent them, analyzing specific words and providing quotations for each.

Minor was a valuable asset to the dictionary’s progress: he meticulously outlined each entry he submitted and didn’t need numerous explanations about the particulars of what he was doing, like some other volunteers. (In his book The Professor and the Madman, Simon Winchester explains that Murray wrote many politely annoyed letters, explaining that there was no need to provide a definition for every occurrence of the word “the”.)

Murray and Minor wrote each other often, but Murray didn’t learn that his most prolific contributor lived in a psychiatric hospital until he traveled 50 miles to see him in 1896, nearly two decades after they first got in touch. This fact helped to explain why Minor had been strangely absent from society parties and talks, despite seeming so engaged with the literary scene of the day.

James Murray, editor and philologist, c. 1910. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Their meeting is described in The Professor and the Madman: Murray arrives at Broadmoor full of excitement and speeches for his unsung hero, and mistakes the governor of the asylum for Minor. “There was a brief pause, a momentary air of mutual embarrassment,” Winchester writes.

Minor was far from stable at the time of the meeting with Murray; in fact his mental state had deteriorated even further since the time of the murder. Haunted by a branding he was forced to give an Irish deserter in the American Civil War, he suffered from paranoid schizophrenia, and had believed he was being molested and poisoned as revenge by Irish men, nightly, for years.

Through the years, the OED’s editor had enlisted hundreds of volunteers around the English-speaking world, and probably took for granted that a mysterious stranger was happy to cite word usage for him all day, because he was editing the most ambitious lexicographical project in the English language to date. Two prior editors had already worked on the dictionary for over 20 years, far past its original two-year prediction of its completion.

This publication goal seems naive in hindsight: the entire project took 70 years. Winchester describes the men who originally proposed the project as “moving blindfolded through molasses;” no one had ever compiled a comprehensive dictionary like this before.

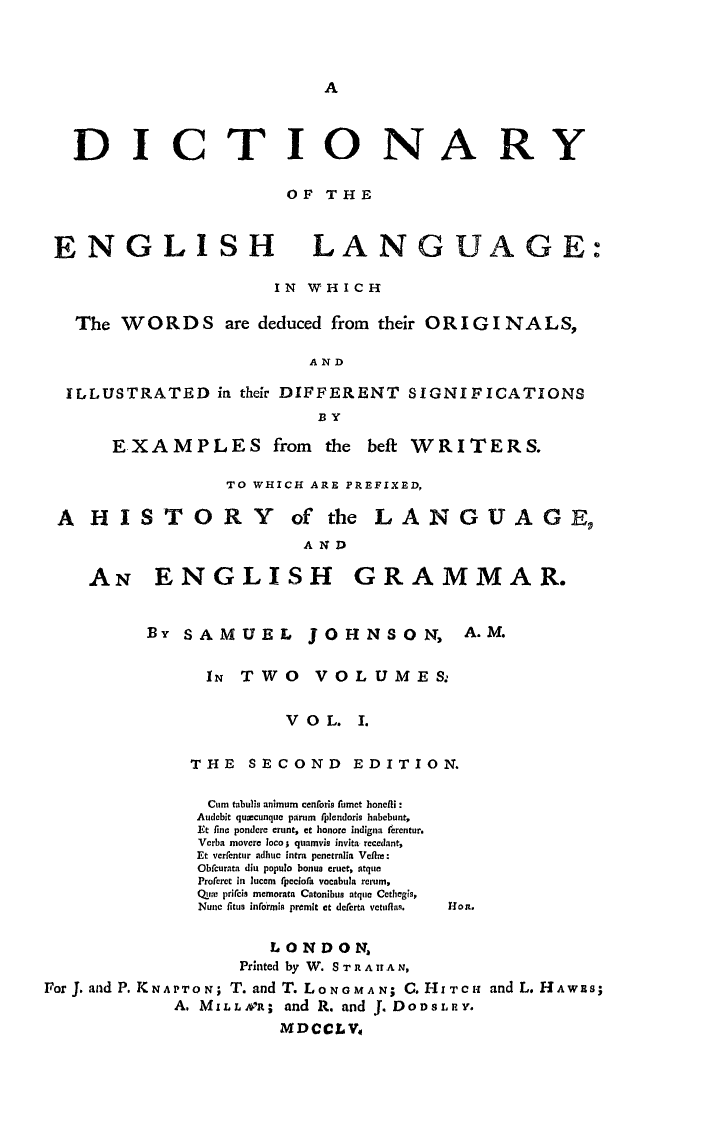

There had been a few earlier attempts at dictionaries, but none of them were entirely useful. Thomas Cooper’s Thesaurus was possibly used by Shakespeare, but was more of a Latin-based guide. Robert Cawdry’s Table Alphabeticall of 1604 was full of single-word definitions, requiring the reader to already grasp another word’s meaning. It wasn’t until Samuel Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language was published in 1755 that anyone came close, but Winchester points out it had more than a few cute personal touches, including the passive aggressive definition of “patron” as “a wretch who supports with indolence, and is paid with flattery.” It was hardly the impartial, scholarly work that the Philological Society, which Murray represented, desired to see.

The title page from the second edition of Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language. Johnson took nearly nine years to complete his dictionary. (Photo; Public Domain/WikiCommons)

English has always been influenced by the cultures that use it–starting from its earliest developments linking the tongues of Anglo-Saxon invaders and their Norse neighbors on the British moors. Mexican Spanish contributed “macho,” “tornado,” and “alligator”, and words that the OED cites from Hindi include “bungalow,” “cot,” and “shampoo,” the last of which first showed up in 1762.

The inclusion of new words has always been controversial. As soon as the first edition was printed in 1928, OED editors Onions and Craige were defending the use of “Americanisms,” telling the New York Times that, “No doubt many of these might be described as slang, but they have a way of rising out of this character and taking their place in serious discourse and writing.”

In 2015, the addition of the word “awesomesauce” on OED’s sister site oxforddictionaries.com led to a few word-snob freak outs on NPR’s comment section. Farmers in the UK wanted the phrase “couch potato” removed from the dictionary in 2005, because they felt potatoes had suffered a bad rap. Of course, language doesn’t work that way; it grows, like a plant with a far-expanding root system, and it doesn’t stop. People will keep hearing new words from internet or text speech, no matter how surprised they may be at the addition of “manspreading.”

“The OED does not aim to add ephemeral words, but that’s in the eye of the beholder,” says Katherine Connor Martin, Head of US Dictionaries at the OED. “Any word can achieve that currency, but we won’t add it if it hasn’t achieved that yet. We are very strict that a number of criteria must be fulfilled.”

Seven of the twenty volumes of the OED second edition. (Photo: Dan/WikiCommons CC BY 2.0)

Everything that is added to or changed in the OED goes through a rigorous process: OED staff mill through traditional printed texts and enormous electronic databases of publications and books for proof of a word’s longevity, popularity and distribution before it is added to the dictionary.

Of course, in a world where crowdsourced guides like Wikipedia and Genius have upended the authority of publishers, the OED faces a struggle to stay relevant. It recently added new features, like audio files of word pronunciation, and a timeline that shows the peaks and valleys of a word’s use. It’s now going through its first massive rewrite, which the OED website says could lend answers to why certain words fell out of popularity, and whether Shakespeare actually invented as many words as people give him credit for.

“We’re going through every entry, reconsidering every aspect of what’s already there,” says Martin, who acknowledges that while there have been many additions to the OED over the years, the dictionary does still contain information that hasn’t been updated since the 19th century.

The third edition of the OED is already more than a third finished—a process that has sped up thanks to current technology. Unlike lexicographers of the 1800s, the OED’s editors can now use a search function to explore old books and articles that were previously impossible to review. With this technology comes the ability to add words more quickly, plus revelations about how long a word has been in use: it was recently discovered that ‘OMG,’ for example, first appeared in 1917, in a letter to Winston Churchill.

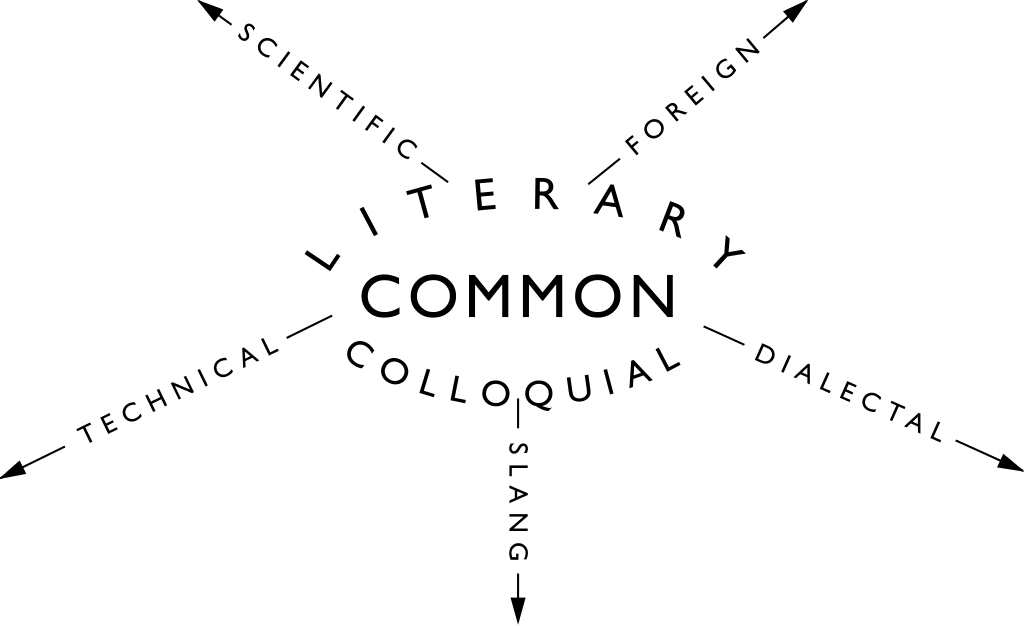

Diagram of the types of English vocabulary included in the OED, devised by James Murray. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

“The language never stops changing–people invent new words at least as fast, if not faster than we are able to record them.” Martin says. “We’ll never have a ‘well, we got it all down now’, because then someone will start saying ‘lumbersexual.’ The task of updating the English language will never be done.”

Of course, new words are the lifeblood of the OED, which still prides itself on being a thorough historical document with contributions from the public. If you want to add to the legacy, you can always send in submissions for consideration, just like Minor did in the old days.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook