Is There Such a Thing as Too Many Blueberries?

The blueberry industry has gotten so big there’s now a glut.

Cultivated blueberries. (Photo: Steven DePolo/CC BY 2.0)

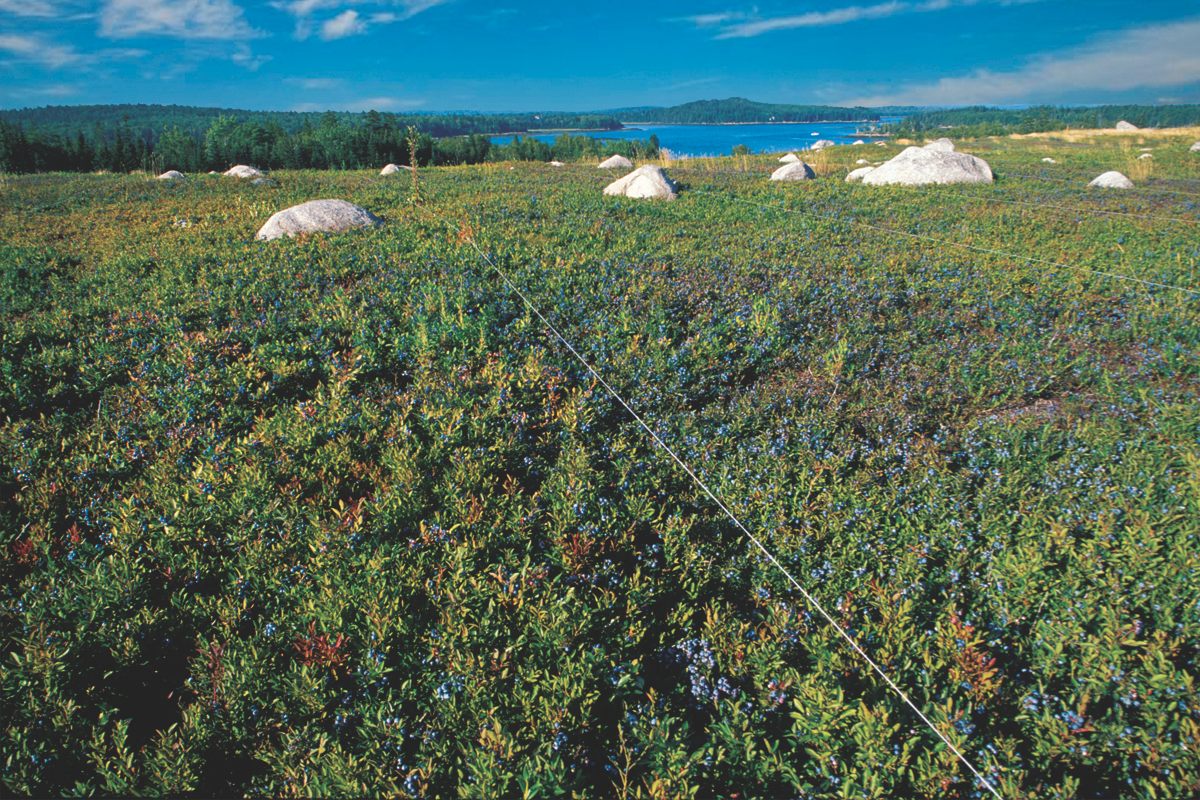

The wild blueberry harvest, up in the blueberry barrens of Maine, starts in July and goes to early September. In these parts of the state, north past Acadia and the touristed summer haunts, there are stretches of land where all you can see are blueberry bushes, low to the ground, for hundreds and hundreds of acres.

Blueberries grow naturally here, in the acidic soil, and for decades growers have been working to better understand them, in order to coax the bushes into producing more fruit. In the past 30 years, they’ve succeeded more than ever before, so that yields have almost doubled since the 1980s.

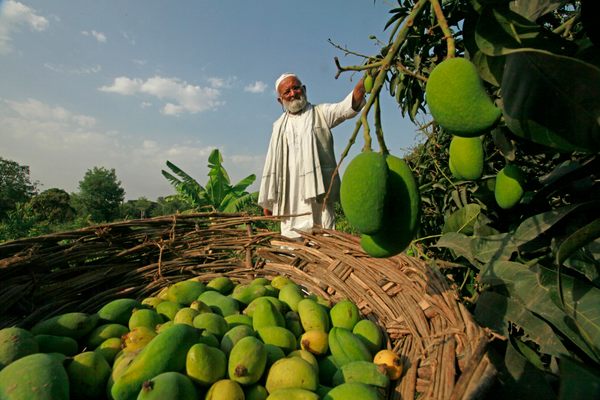

But as the supply of wild blueberries has increased, so has the production of their fatter, cultivated cousins, which in America is three times as large as of wild blueberries. At the same time, blueberry cultivation has spread around the world, to Mexico, Chile, New Zealand, Spain, Poland, South Africa, and China. There are more blueberries being harvested now than at any other point in history—so many that despite the industry’s best efforts to market them, there are more blueberries than people are ready to eat.

The blueberry industry is nowhere near the scale of Big Corn, but blueberries are now big enough business that when supply is high and prices drop low, the government considers stepping in. There may not be Big Blueberry yet, but the industry has enough economic heft and political clout that in the past few years the USDA has increased its spending on blueberries. The danger is that, like Violet Beauregarde, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory’s famous girl-turned-overstuffed-blueberry, the industry will get so large and plump it will be helpless without assistance.

Wild blueberries, ready to be picked. (Photo: Allagash Brewing/CC BY 2.0)

Most of the fruits and vegetables we eat were tamed long ago, but the blueberry is relatively recent acquisition. The first cultivated crop of blueberries was harvested just a century back, in 1916, and it created a split in the blueberry world.

Today, two main types of blueberries are sold in North America. The fat, farmed blueberries, the ones you’ll usually find fresh at grocery stores, likely come from New Jersey, Michigan, Washington, and Georgia, and in the winter are imported from further south. The smaller, wild ones, from Maine and Canada, are more likely to show up in the frozen food section or in packaged or prepared food.

The wild relatives of most fruits and vegetables are no longer of much interest to us as foodstuff, but these northern, wild blueberries are unusual. They remain tasty little balls of sweet-tart fruit, and while they’re not domesticated, they are under the influence of humans.

Blueberry barrens in Maine. (Photo: Wild Blueberry Association of North America)

Wild blueberry bushes are survivors. They thrive in Maine and Canada along glaciated plains that are inhospitable to many plants. Unlike cultivated blueberries, wild blueberries can’t be planted—and when they do spread, they grow slowly, so that a new stand can take a decade to become productive. But they do well in disturbed places: when a fire sweeps through, they’re the type of plants that jump right back and start working as fast as they can.

“If you get a blow down in the forest, they respond rapidly and produce fruit so that birds and bears eat and distribute it,” says David Yarborough, a wild blueberry specialist at the University of Maine Cooperative Extension. “We’re taking advantage of that adaptive strategy to produce a wild crop in a commercial manner.”

In other words, wild blueberry farmers try to create conditions for blueberry bushes to produce as much fruit as possible and swoop in to collect it. In practice, that means controlling weeds, maintaining a regular cycle of burns, and bringing in extra bees to help with pollination. These strategies have dramatically increased the Maine harvest from an annual average yield of 55 millions of pounds from 1985 to 1995 to an annual average of 93.5 million in the past decade.

At the same time, though, cultivated blueberries were going through their own boom. In 2014, world production hit one billion pounds, and one industry group estimated production in North America alone could hit one billion pounds by 2020.

Blueberry barrens turn bright red in the fall. (Photo: Wild Blueberry Association of North America )

Despite the antioxidants, despite the smoothie trend, despite blueberry industry efforts to find new ways to use blueberries, that is too many blueberries. Prices have dropped; for U.S. wild blueberries, which compete with Canadian crops, the exchange rate, which means Canadian farmers can offer an even lower price, is hurting too.

This summer, the USDA chose to support both the cultivated and wild blueberry industry by buying up a portion of those massive piles of blueberries. These buys are part of a food assistance program, funded by taxes on imports, and every year the USDA has some discretion on what it purchases. One of the aims of the program is to support farmers by keeping prices from bouncing around too much, but the industry has to make a case to the agency that it should be included.

In 2013, for instance, wild and cultivated blueberries ranked fourth and fifth, by dollar amount, in the program’s contingency purchases (after turkey, chicken products and potatoes, but ahead of cranberries, grapefruit juice and catfish products). When the wild blueberry industry asked for the USDA to buy blueberries in 2015, though, the agency declined.

The wild blueberry industry has found new ways to take advantage of government purchasing, too, by making the case for including frozen blueberries in a fresh fruit program for school lunches. But these sorts of strategies have become more necessary as overall blueberry production has grown. “We as a commodity group have received bonus buys off and on since the mid-2000s,” says Nancy McBrady, the executive director of the Wild Blueberry Commission of Maine. “It’s taken on a different color and a sense of urgency these last couple of years.”

Has the world reached its capacity for blueberries? The industry doesn’t think so, of course. The cultivated industry talks about introducing new markets to blueberries. (An industry report notes, “Ten years ago, we were told that Latin Americans did not like blueberries. Today Mexico is one of our leading markets for frozen blueberries. Now the rest of the Americas—the area from the Panama Canal to the Arctic—are turning on to blueberries!”)

The wild blueberry industry likes to talk about how wild blueberries have an extra-high wallop of antioxidants, and in our health-obsessed age, it looks like that’s paying off: as Eater reported in July, they’re showing up everywhere from lobster salad to Panera scones and Clif bars. Perhaps the world’s fruit fans just don’t realize yet how many blueberries they want.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook