The Impossible Task of Reconstructing the Rules to an Ancient Board Game

How would you figure out Monopoly with no instructions and half the pieces missing?

For hundreds of years, the two-chambered tomb of a fourth-century Germanic chieftain lay undisturbed in Poprad, Slovakia’s 10th largest city. Then, in 2005, construction began on a new industrial park and the grave was revealed. Archaeologists found a wealth of treasures, including wooden furniture, pottery, an ancient bucket, and half of the skeleton of its occupant. It was an interesting find, if not too unusual, bar a mysterious wooden playing board. It was carved with a chess-like grid—17 by 18 squares—and came with a handful of black and white counters in different sizes.

Ulrich Schädler is a German games historian at the Swiss University of Freiburg and editor of the journal Board Games Studies. He also heads the Swiss Museum of Games, a curious collection of indoor and outdoor pastimes housed a castle on the banks of Lake Geneva. Schädler has been working on the Poprad game for some time. Is it a complete set? What are the rules or object of the game? Despite his expertise—and Germans are known for their board game savvy—the sparse components remain a mystery to him.

“Imagine you find a Monopoly board and a handful of street cards plus one little tin hat and a little tin shoe, nothing else, and no trace of something similar in the written sources,” he says. “It is absurd to think one might ever be able to reconstruct the Monopoly rules in all their details.” The rules to any game—chess, rummy, Ticket to Ride—are rife with details that might not be apparent from looking at the pieces, cards, or boards themselves. After all, there’s only so much one can surmise from a little tin hat, a tiny rampart, or an ace of spades.

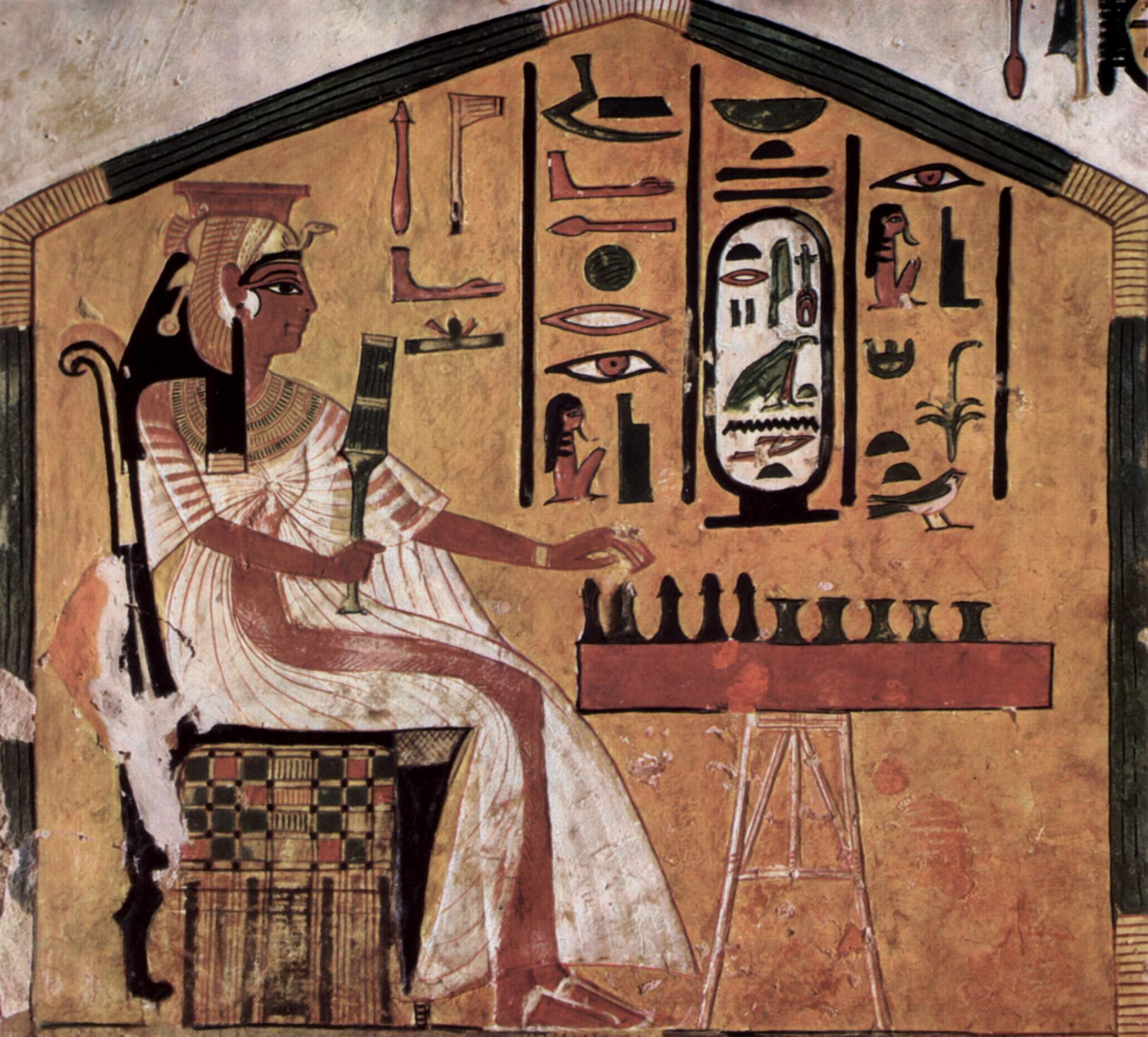

Take latrunculi. This two-player strategy game was played throughout the Roman Empire, and seems to have been a spin-off of a Greek predecessor, petteia. People played it on boards etched into the floors of temples—grids of seven by eight, eight by eight, or sometimes even eight by 12. We know it was a militaristic strategy game, but beyond that the rules and goals begin to get a little murky. Another complicating factor, writes Walter Crist, who studies ancient games at Arizona State University, is that the rules to these very popular ancient games may have changed over the millennia they were played, with subtle variations in house rules.

To solve such puzzles, scholars often turn to literary references, where ancient authors sometimes offer details in poetry or opinion. But, in the same way that someone might make an offhand reference to “Monopoly money,” a mere mention of a game might mean little to a reader unfamiliar with it. (Imagine trying to reconstruct how chess is played from the works of Vladimir Nabokov.) Ancient writers have plenty to say about latrunculi, but it’s not always all that helpful. Plato describes Socrates’s opponents as being like “unskillful [latrunculi] players [with] nothing to say in this new game of which words are the counters; and yet all the time they are in the right.” Ovid, in his Art of Love, says that the lover must be like the latrunculi player, playing with “skill and caution.”

Comments like these suggest that the game is one of strategy and planning, but tell us little more than that. Other references are a little clearer. The epigrammist Martial writes, “If you play the war-game of robbers in ambush these [latrunculi] glass pieces will be your soldiers and their enemies.” From such explanations, scholars have attempted to reconstruct the rules of the game, though absolute accuracy is impossible. “The only thing one can do is to grasp some idea about the principles,” Schädler says.

Then, of course, there’s the fact that there is likely no one set of rules. The idea that there was one “official” way to play latrunculi—common to Rome, Egypt, Britain, Tunisia, and Germany—is absurd, Schädler says. A game as simple as hide-and-seek has regional variations (How long do you count? When do you stop looking?), and while FIFA has rules for soccer, they’re hardly followed in backyards and on beaches around the world. Even chess was played for well over 1,000 years before its rules were standardized.

Schädler’s 2001 reconstruction of the rules of latrunculi draws from poetry and epigrams alike, as well as the game boards scratched into ancient roof tiles or the steps of the Parthenon. His version, though playable, is still a little vague, with the exact number of pieces to be decided on by the players. (He knows there must have been a lot—perhaps between 16 and 24—because one reference describes how the board “rattles with the crowd of pieces.”) Were suicide moves, in which players can take their own pieces, allowed? Maybe, maybe not—but they’re part of Schädler’s take anyway. Try it at home—all it take is a checkers board and up to 24 counters per player.

For now, Schädler has no such plans for the board found in Poprad—there are still far too many questions. The board may resemble a latrunculi board, but it’s far larger than any seen before, he says, and the different-sized pieces raise more uncertainties. On top of that, it comes from a time 300 years after the last known reference to latrunculi. In the absence of textual references or a suite of additional evidence, this game is likely to remain a mystery. Spare a thought, however, for those who may one day be tasked with figuring out our modern board games, hundreds of years from now, trying to work out why there is a candlestick but no other home furnishings in the Clue box.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook