Need a Last-Minute Mariachi Band in L.A.? Go to This Plaza

Boyle Heights has long been a gathering place for gig-ready Mexican musicians.

“Are you going to turn us into immigration?”

The man asking this has been in California since 1969. Originally from Mexico, he is a mariachi. He has spent his life playing traditional Mexican music all over Southern California. We are standing in Mariachi Plaza, in the predominately Latino neighborhood of Boyle Heights, just east of downtown Los Angeles.

This unassuming plaza, with its coffee shop, metro station, gazebo, AA meeting room, and faded murals, is the epicenter of mariachi music in America. In the world, it is only topped by Mexico City’s famed Plaza Garibaldi, the historic square that mariachis have called home for decades.

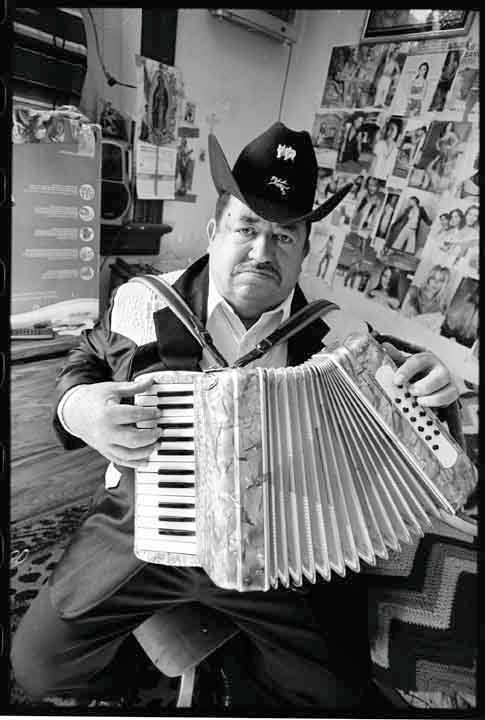

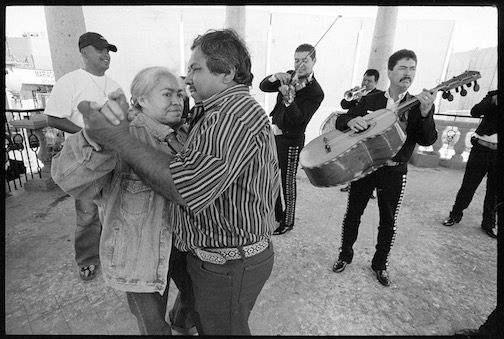

Men in charro jackets sit with battered instruments, chatting and laughing, waiting for a gig to appear. Every now and then a car drives up. Someone is looking for a group of mariachis to play for a wedding, quinceañera, funeral, or even a divorce. A cluster of men pile into a van, and off they go to their next gig.

Mariachi music, with its stories of love and loss and joy, is considered essential at any major Mexican event in Los Angeles. “For every Mexican, and I mean every Mexican, whether you live in Mexico or not, mariachi music is no less than the cry of your soul,” Boyle Heights native Evangeline Ordaz-Molina wrote in the book Hotel Mariachi: Urban Space and Cultural Heritage in Los Angeles. “When we hear that first strum of the mariachi guitar, our hearts literally flutter, and when the violins and trumpets come in, our lungs fill.”

The men (and a few women) who populate Mariachi Plaza are understandably suspicious of outsiders, but speak of a life filled with waiting, interspersed with moments of artistic fulfillment. They stand around a van, out of which an older mariachi—unable to perform anymore due to the long hours of standing during a gig—sells mariachi boots and belts, and water for the hot days in the unshaded plaza. He also sells CDs, so mariachis can teach themselves new popular songs that they may be asked to perform.

Many of them are in the plaza almost every day, year-round. Some only come up to Los Angeles from Easter to Christmas—when there is the most work. There is competition among the mariachis, and many of the old timers believe that there has recently been an infusion of less skilled performers, who simply dress the part and attempt to undercut them. Left to their druthers, the mariachis would play the old songs, but the newest trend is banda music, and big bands featuring 20 or so wind instruments. Bands are often fluid, and leaders search the plaza and the area around it for the musicians they need for a given gig.

Saturday is a day of celebration in the plaza. Groups of celebrants, be they weddings or birthday or anniversary parties, come to the plaza to be serenaded by the mariachis.

Most mariachis have been playing since they were children. Like many artists, they work other jobs to support themselves, often avoiding heavy manual labor that could affect their hands. “The business of selling mariachi music is conducted much like other day labor is transacted in Los Angeles,” Ordaz-Molina wrote. “Mariachis wait for customers at the donut shop, turned plaza, turned metro station, on the corner of First and Boyle in Boyle Heights, and when the customers arrive they negotiate a price, get an address, and four or five musicians get into a car and go.”

According to longtime residents, mariachis have called this intersection home since as far back as the 1930s. Originally it was just a traffic triangle in a quiet middle-class suburb of Los Angeles. By the 1960s, it featured a donut shop that was the mariachis’ unofficial headquarters. In the 1990s, the triangle was turned into a plaza dedicated to the mariachis, complete with a performance kiosk and a statue of their patron saint, Saint Cecilia. In 2009, the L.A. metro’s gold line extension opened at Mariachi Plaza, sparking well-founded fears of encroaching gentrification.

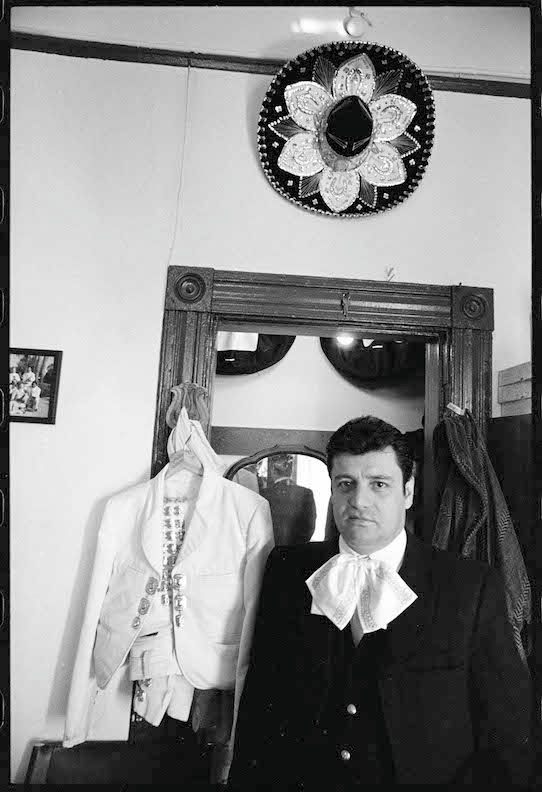

Throughout all this change, the mariachis have remained a constant. Ordaz-Molina recalled coming back to Boyle Heights after law school and being comforted by their continued presence. “I would drive by the hotel and donut shop (the plaza was still just a traffic triangle with a donut shop sitting on it),” she wrote, “just to catch a glimpse of the romantic figures in their tight black suits with silver buttons running up the sides of their pants and white embroidery decorating their short black jackets.”

Over the decades, commercial enterprises catering to mariachis have sprung up all around the plaza. There are instrument stores, performance spaces, and restaurants. At dinner theaters like the legendary El Mercadito Mariachi Restaurant, mariachis play nightly, whether to a table of one or a packed house.

Tailor Jorge Tello, known as “el maestro,” is a friendly man with a large smile, who has dressed the mariachis of Boyle Heights for over 30 years. In his tailoring shop La Casa del Mariachi, just across the street from the plaza, he shows off beautiful custom-made suits, some as expensive as $4000. “They are all handmade,” he says cheerfully.

Many mariachis also live in the neighborhood directly surrounding the plaza. Since the 1960s, the most famous of these residences was the Boyle Hotel (also known as the Cummings Block), often called the “Hotel Mariachi.” This beautiful Queen Anne Italianate building was originally built in 1889, by L.A. businessman George Cummings and his wife, Sacramenta Lopez, on land she had inherited from her family. The hotel had fallen into disrepair by the second World War and became a place where mostly single mariachis could live inexpensively. “They could be right there, at the Plaza,” Catherine Kurland, author of Hotel Mariachi, says, “so that if one of the mariachis got a gig he could just call up to the rest of the musicians and say, ‘Come on down, let’s go!’”

Kurland, a direct descendant of Sacramenta Lopez, rediscovered her family’s old hotel one day in 2003.She and her niece were having lunch in Boyle Heights when they decided to look for the Boyle Hotel. They saw that a door to the dilapidated building was open. “My niece and I sort of impulsively ran up the stairs and the door opened and we found ourselves on this landing,” she says, “and we looked around and were surrounded by men, in these black suits, or some states of undress, and we realized, it dawned on us that these are mariachis!”

She soon became immersed in the living history of her family’s former hotel. “When I first saw it, about 80 percent of the residents—there were maybe 110 residents- in about 60 units, were mariachi,” she says. “Two of them could live cheaply in a little room with a little hot plate and a bathroom down the hall.” She worked to have the building declared a Los Angeles Cultural Historic Landmark, partially to save it from being torn down by developers. She also produced the book Hotel Mariachi, along with Enrique R. Lamadrid, Evangeline Ordaz-Molina and photographer Miguel Gandert, her professor at the University of New Mexico. They spent hours speaking with and documenting the lives of the mariachis, including men like Luisiito García, called Don Luis, who had lived in the hotel since the 1960s.

In 2007, the East L.A. Community Corporation, a non-profit organization dedicated to providing affordable, up-to-code residences in Boyle Heights, bought the hotel for around $3.1 million. The group, headed by Maria Cabildo and Evangeline Ordaz-Molina, consulted the mariachis to ascertain what they needed—a place to store instruments, a computer room, and rehearsal space were at the top of their list.

By the time the hotel was renovated to the tune of $24.6 million in 2012, many of the mariachis who had lived there had already found other housing or had been priced out of the hotel by rising costs.

As Boyle Heights becomes trendier, mariachis continue to be priced out of their homes neighboring Mariachi Plaza. In April of 2017, LA Weekly writer Jason McGahan reported that many mariachis were in danger of being forced out of their apartments, with some of their rents being raised this year by as much as 80 percent.

Despite the continuing threats to their way of life, the mariachis of Mariachi Plaza endure. “I enjoy it,” one man says. “It’s my culture. It’s…” He puts his hands to his heart and smiles.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook