Meet the Brain Banker Who Keeps Thousands of Brains In His Lab In the Bronx

Brain scans at a research facility. (Photo: Tushchakorn/shutterstock.com)

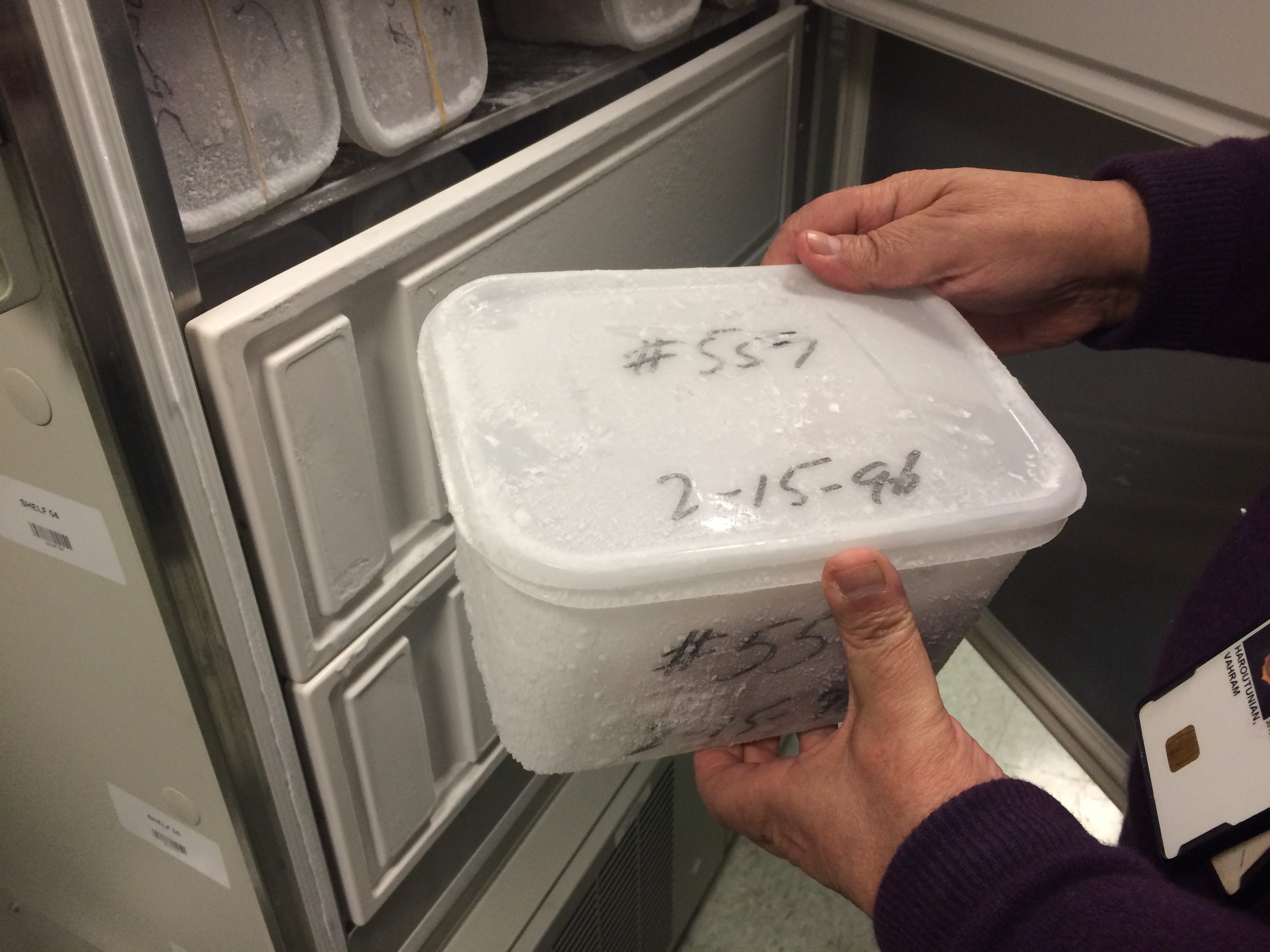

Dr. Vahram Haroutunian opened the plastic tupperware with a careful, rigid pop. Inside are over a dozen pink, carefully freeze-packed slices of a human brain. White clouds of cold air escaped from the door, where dozens of these containers were neatly stacked and stored.

“This is a case that we got in February of ’96,” Haroutunian says. The brain slices are individually sealed in thick, vacuum-sealed plastic, see-through like a frosty windowpane. When looking at them, it’s hard not to think of frozen pork chops at the grocery store. Each freezer holds about 100 donations, and there are over a dozen freezers here. I am standing in a room with the brains of over a thousand people.

Haroutunian is the director of the Mount Sinai NIH Brain and Tissue Repository at the James J. Peters VA Medical Center, in the Bronx. Known as a brain bank, this lab is one of five in a multi-state consortium called the NeuroBioBank that stores donated brains for neuroscientists to study brain function, mental illness and degenerative disease.

A single brain can, over the course of decades, reach laboratories all over the world. “We have five requests pending at any point and time—it’s a continuous thing,” says Haroutunian. “It’s kind of like going in and asking for a mortgage. We negotiate, and what happens is all the NeuroBio banks look at the request that has come in, and they chime in if they have the specific cases or brain areas that are of interest.”

The idea is to pool the efforts of each bank to maximize the brain tissue available for worldwide research. A scientist in France might ask for 15,000 samples of a specific part of the brain, for instance, and then the request is forwarded to the member banks, who will work together to contribute as many of the total number of samples needed as they can.

Dr. Vahram Haroutunian in front of fixed brain specimens at the brain bank. (Photo: Natalie Zarrelli)

Haroutunian has been working at his brain bank for 34 years, since its previous incarnation as an Alzheimer’s research center in the ‘80s. At the time, Haroutunian treated and studied patients who exhibited Alzheimer’s symptoms, but couldn’t officially diagnose the disease without looking at the brain tissue itself. After a visiting NIH official asked about this problem, Haroutunian’s research center was inspired to store and collect brains, eventually growing to incorporate those of several other degenerative diseases, and even brains of completely healthy individuals.

“We and everyone else who came after us realized that there was a lot more,” says Haroutunian. And there is more. He takes me into the next room, which looks like a classic sci-fi movie scene—it is lined with brains preserved in jars.

Up close, I can see the small curves and wrinkles that used to hold worries and memories. Haroutunian explains that preserving the brain in formalin, a formaldehyde product, helps protect the structure of soft brain tissue, so its anatomy and cell structure are easily seen.

The freezer where specimens are kept, labeled by serial number. (Photo: Natalie Zarrelli)

In the freezers and jars, the brains are labeled by serial number. As with many professions that involve human organs, the bank’s staff keep the brains separate from their former human identities while dissecting and studying them—a necessary combination of respect and anonymity that helps them perform their work. There is no mention of the donor’s name, though the brain bank knows it from medical records; Haroutunian refers to the brains only as “specimens.” A red sticker on a freezer door reminds, a bit ominously, that it is not a place to store food or drink.

All this is not to say that the donor and donor’s family aren’t treated with empathy; in fact, an enormous amount of time is spent assuring consent from the donor, and after the donor’s death, from their next of kin. This presents brain banks with a challenge when asking for organs from grieving families. The brain is an organ that is particularly human and impossible to replace–it shapes both our personalities and identities—but researchers sorely need them.

Brain banks do what they can to make their good intentions known: pamphlets emphasize the potential of saving lives, and show happy, brain-having families. The Columbia University Brain Bank allays fears with their FAQ, assuring potential donors and their families that open casket funerals are possible after donating a brain. Haroutunian’s lab employs a donation coordinator, Maxwell Bustamante, who is the first contact for a donor’s family, and answers questions day and night.

These days, most donations are made courtesy of people that Haroutunian has never met, generally after a call comes in from New York’s optimistically-named organ donation center, LiveOnNY. Once consent is given, brain banks act fast. Brain tissue degrades quickly after death, which limits what they can be used for. Haroutunian says that while a 48-hour-old brain can be studied for anatomy, you probably can’t observe a specific protein in its cells, for example. If the donor’s death happens far away, they pack the brain in a box of ice, and ship it over to the lab for deeper freezing and processing.

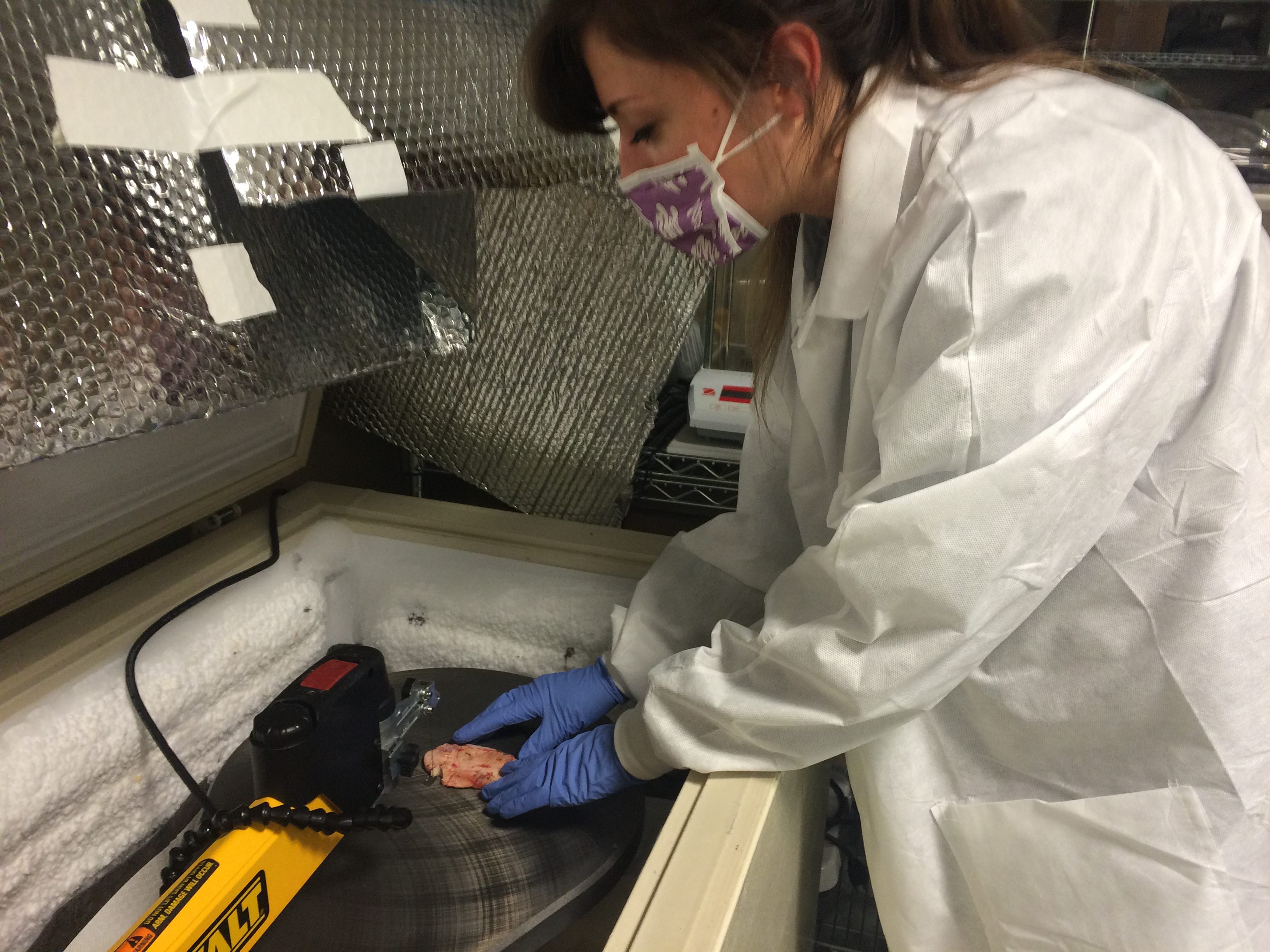

Lab technician Christine processes a brain at the Mount Sinai NIH Brain and Tissue Repository. (Photo: Natalie Zarrelli)

In Haroutunian’s lab, technicians separate the brain into its left and right hemispheres. The right half is cut into pieces and fixed in jars for anatomical studies, and the left is sliced and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and can later be ground into smaller pieces using a nitrogen-cooled mortar and pestle. “The idea is preserving the tissue and the biochemistry of the specimen as permanently as we can, and the best we can do with modern technology is to keep it as cold as is practically feasible,” Haroutunian explains.

Lab technicians note the brain sections–like the hippocampus or prefrontal cortex–wrap the pieces in plastic, and store them away.“At that point, everything comes almost to a standstill, while we go on an information gathering mission,” Haroutunian says. He and his staff investigate the donor, through hospital records and the family, to fill the gaps of the donor’s medical history.

“As a brain banker, I have to be thinking 10, 15, 20 years ahead. I’m not arrogant enough to think that what medical features I think are important today are going to be important 30 years from now,” he says, noting that the oldest brain stored at the bank was donated in 1983, and they’re still using it. “Did they take a multivitamin? I don’t think that’s going to be important—but what do I know?” Haroutunian laughs. “Was there toenail fungus that was diagnosed during the last year? Maybe 50 years from now, that will be important.”

New discoveries involving brain donations are happening all the time. Just this year, Haroutunian’s lab continued research that ties a gene to an anomaly in the brain nerve coating of schizophrenic patients. This is significant —at first glance, schizophrenic brains are not physically different from one without the disease. “We can almost diagnose schizophrenia by looking at how these genes are behaving…to the point of creating transgenic animal models,” says Haroutunian. Now, they are activating a portion of these genes in rats, to see if this results in the same nerve characteristics present in schizophrenic humans. Discoveries like these can only be found through brain and tissue donations.

Dr. Lawrence Honig, professor of clinical neurology at the Columbia University Medical Center, says that brain banks are vital to his work. “We can find out what molecules, what pathways are changed or altered; what make the disease progress,” says Honig. “You can’t find that from asking [the patient] questions.” Honig, who works on the clinical side of the brain bank world through his university, treats patients with neurodegenerative diseases during their life, but uses research from donated brains to understand how to best treat his patients.

That connection to the clinical side of the neuroscience world seems to be more relevant than ever. “As of now, what’s the fastest growing segment of the US population? People over the age of 85,” says Haroutunian. The longer people live, the more we need to understand degenerative diseases related to aging. With this comes new mysteries: older patients are often misdiagnosed with Alzheimer’s, and Haroutunian’s lab only learns the patients never had it when they examine their brains. “Maybe they have something else, and that whatever it is, is letting centenarians not die of cancer,” he offers. Brain banks and scientists the world over will be looking to find out.

You might be wondering if you can contribute to solving these new puzzles some day. Haroutunian says that you can—though he hopes your chance to donate your own brain doesn’t happen any time soon. If you do eventually want to donate a brain, you can start by filling out a form at your local tissue repository, or if you’re signed up as an organ donor, donation centers will likely give a call to the brain bankers near you.

This story appeared as part of Atlas Obscura’s Time Week, a week devoted to the perplexing particulars of keeping time throughout history. See more Time Week stories here.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook