What Do We Really Know About the History of the Printing Press?

To get the whole story, you’ll need a particle accelerator.

When Angelica Noh boarded a 12-hour flight from Seoul to San Francisco in July, she carried some unusual cargo. Traveling in business class with Noh, a program specialist at UNESCO whose focus is on endangered documentary heritage, was a locked carry-on bag containing 40 irreplaceable pages from historic Korean texts, some almost 900 years old.

From the outside, Noh’s bag was nondescript—she didn’t want to draw attention to herself—but inside, the leaves of mulberry paper were carefully packed. The team at UNESCO in South Korea had sandwiched each page between new blank sheets of mulberry paper and then put them in individual plastic folders before placing them in the suitcase. Making sure that these documents made it to California safely was key, as they could reveal previously unknown history about the evolution of the printing press.

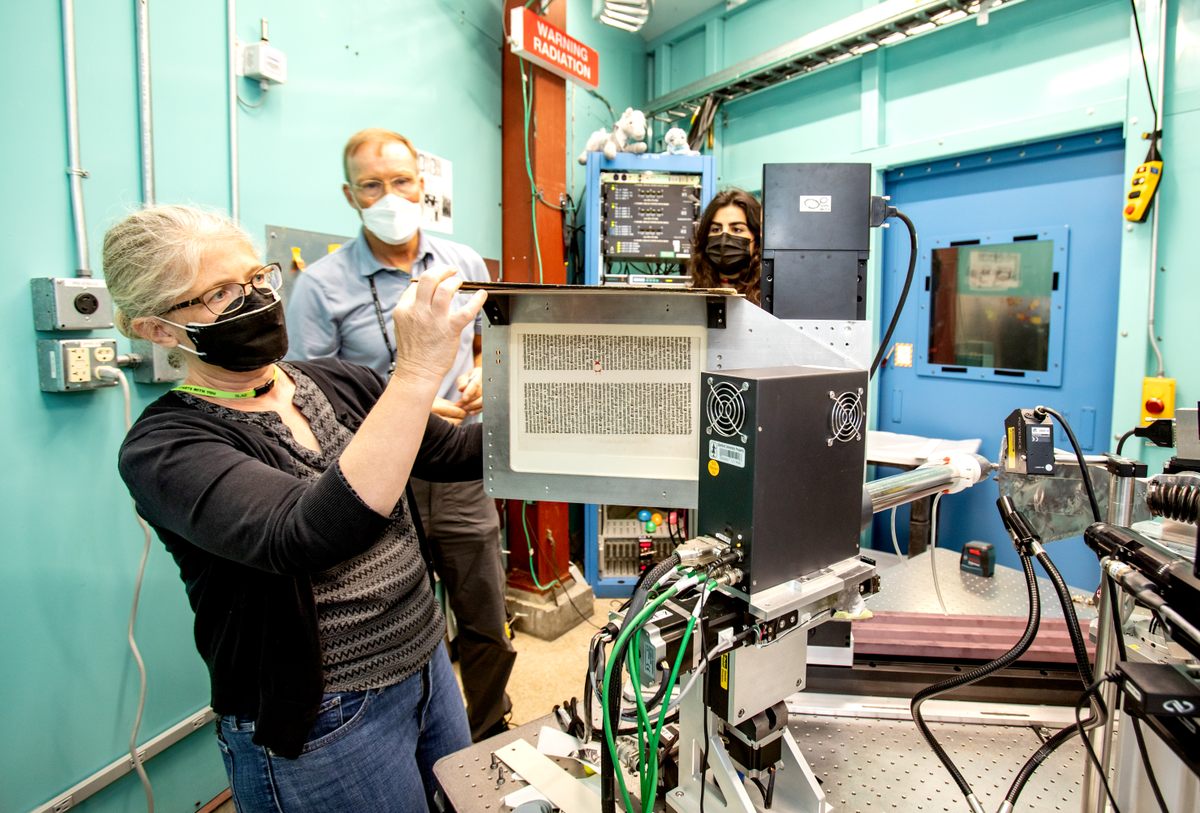

During the summer of 2021, UNESCO’s International Center for Documentary Heritage (ICDH) built a team of nearly 50 people, including Noh, spanning across time zones and academic fields from physics to bookbinding preservation to study these and other historic texts to expand our knowledge of the culture and history of printing technology in the Eastern and Western worlds.

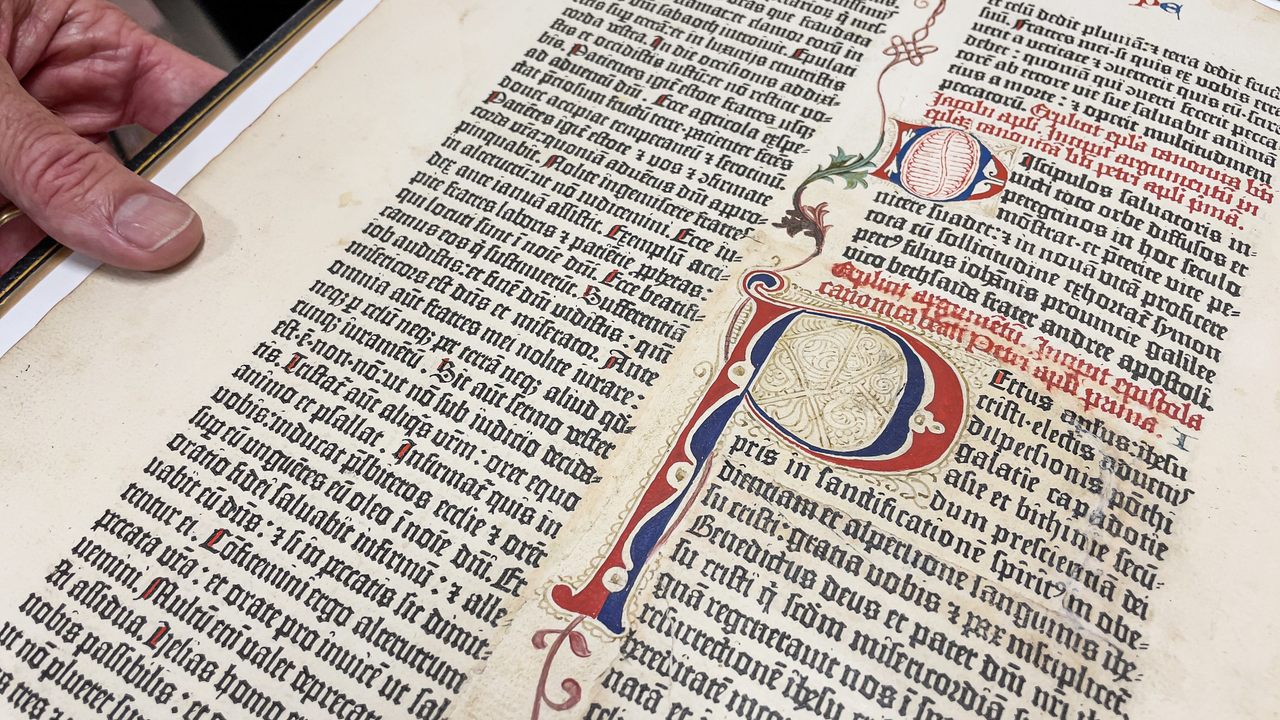

At Stanford University in California, where physicists at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory eagerly awaited Noh and her luggage, researchers are now in the process of analyzing these texts. They want to know what happened in the history of printing between the production of the Jikji, a Korean Buddhist document published in Heungdeok Temple in 1377, the earliest printed book on record, and the Gutenberg Bible, printed in Mainz, Germany in 1455.

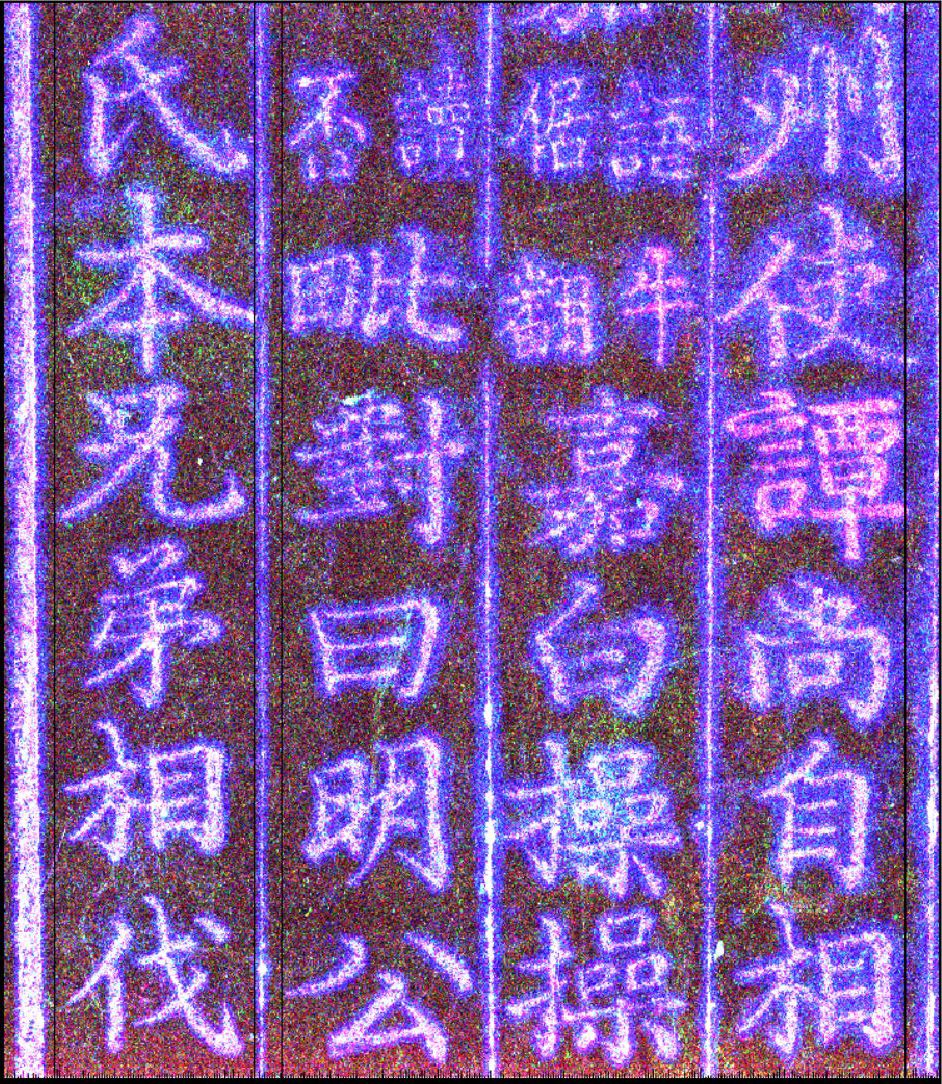

The 40 Korean pages as well as 20 Western pages—including an early printing of The Canterbury Tales— have been studied using a synchrotron, a type of particle accelerator, to take fluorescence scans. Think of it like the X-rays taken at a doctor’s visit. The radiation produced by the synchrotron takes a snapshot of the chemicals on the object that are invisible to the naked eye. These images will help scientists determine whether the moveable types used on each page left any residue, which would teach them more about the original printing process. Minhal Gardezi, a PhD student in physics at the University of Wisconsin Madison, says that the ultimate goal is to see if they can get traces of the printing press itself. “We can compare that against what the scholars know about what papers and inks were being used back then,” she says.

The process of understanding what these scanned images actually mean will take some time, but Gardezi is optimistic that the findings will be impactful. “Whether it proves a connection or disproves the connection, or does neither, we will learn a lot about these early printing presses that we didn’t know before,” she says.

If a connection between the two printing presses is revealed, it would introduce what Noh calls the Type Road, something like the transfer of culture that occurred along the Silk Road. “We could follow the trace of the Type Road not just to see Korean printing culture and German printing culture, but also other countries’ printing cultures,” she says.

But if scientists aren’t able to see a clear connection between early Eastern and Western texts, the project will still emphasize that our understanding of history is guided by who we tend to put at the center. “Oftentimes, history is Eurocentric, and even though we do learn about things that happened in Asia, or in other parts of the world, it’s sometimes hard to remember that that history is happening at the same time in both areas,” Gardezi explains.

What if Gutenberg was influenced by the printing press already existing in Korea? What if he actually did invent his press independently? So far, there is no strong evidence for either case but the possibilities are what makes this work exciting. “If there’s some sort of connection between East and West, it really puts a whole new light on the unification of these regions and how they’re organically impacting each other and how they may have been much more connected than we are inclined to believe,” Gardezi says.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook