Ngonnso Will Finally Come Home to Cameroon

The only known depiction of the queen mother of the Nso people was taken to Germany 120 years ago.

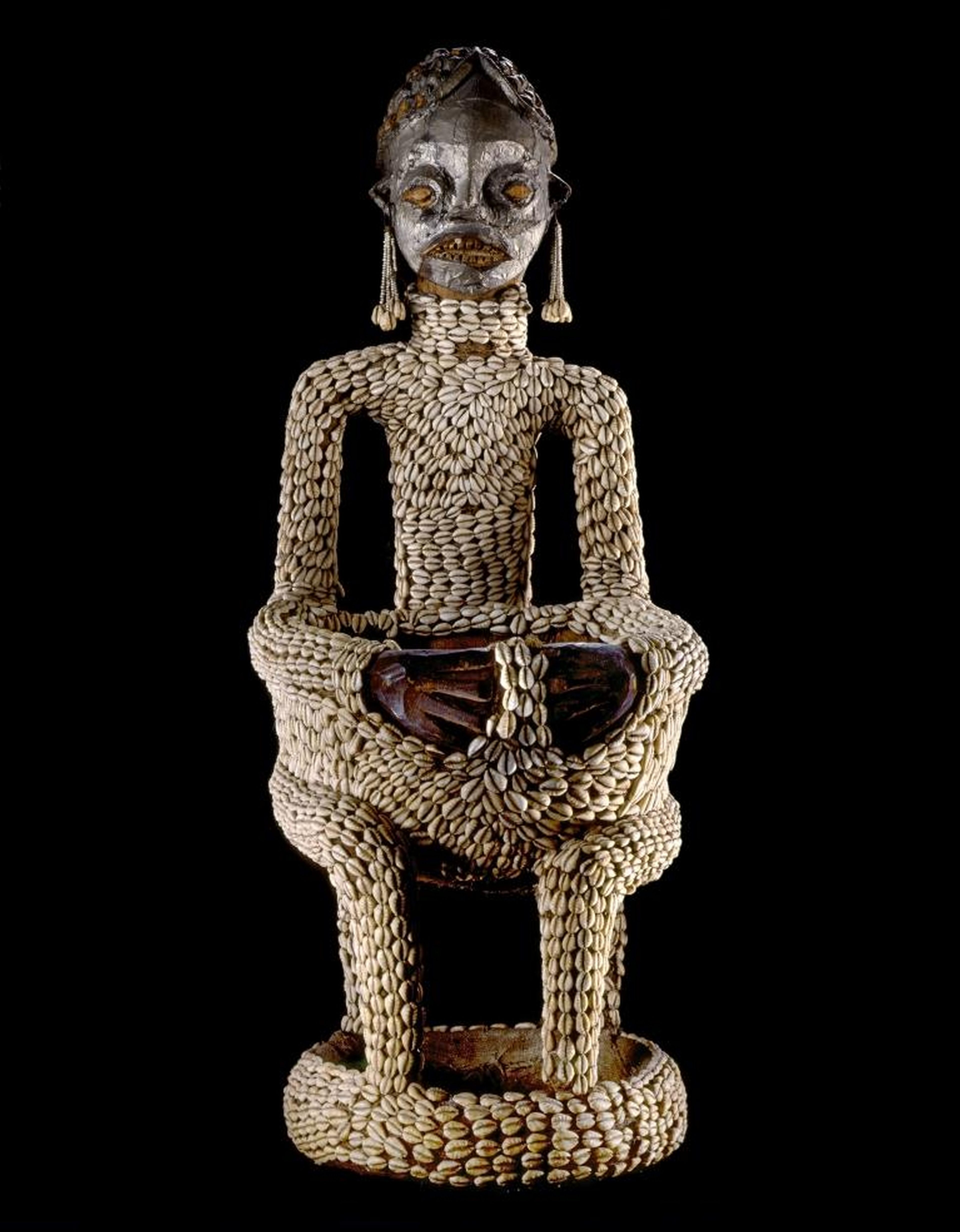

For years, Sylvie Njobati would walk by a life-size statue of a woman in Kumbo, in the northwest region of Cameroon. Meticulously outlined with hundreds of seashells, the statue depicts Ngonnso, the queen mother of Nso people, a cultural group in the region whose origin can be traced to the 14th century.

According to Nso oral history, Ngonnso founded the Nso kingdom after a brutal conflict with her two brothers. “She was able to conquer, to defeat, to ensure that all of Nso people stayed together,” said Njobati, 30-year-old Nso activist and arts manager. For them, Ngonnso embodies their history and identity.

But the Ngonnso statue sitting at the center of the Nso palace compound in Kumbo is only a replica made in 2008. The real one, which dates back hundreds of years, is 3,000 miles away in Germany in a glass box at Berlin’s Humboldt Forum, a new museum which has been mired in controversies for its connection to German colonial past.

“The [original] statue is the only thing we have of her in image,” said Njobati, who founded the Bring Back Ngonnso campaign in 2018. The replica, created for an annual cultural festival that celebrates Ngonnso, is “to keep the memory alive, to remind the people that we have a bigger battle.”

The statue was taken by Kurt Pavel, a German colonial commander during his first visit to the Nso Kingdom in 1902. There is no written record of how he acquired the statue exactly, but one fact is certain—Pavel’s visit was a “punitive expedition” accompanied by soldiers and armed porters aimed to intimidate Nso people into submitting to German colonial rule, according to Anne Splettstößer, an ethnologist who detailed the historical context in which Ngonnso was taken in her publication Contested Collections.

In 1903, Pavel gave the statue to the Ethnological Museum in Berlin. Today, the museum is overseen by the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation, also known as the SPK, which long claimed to be the statue’s legitimate owner. The Nso community, on the other hand, argued that the statue could not have been willingly offered to the Germans because of its historical and spiritual significance. In June 2022, the museum reconsidered its position and pledged to work with Cameroonian officials to return the statue.

Before the Ngonnso statue was taken to Germany, generations of Nso chiefs stored the statue in a sacred chamber and only used it in celebrations and rituals, Njobati said. “These are royal objects and cannot be sold.”

For years, the Ngonnso statue stayed in the basement of the Ethnological Museum in southwestern Berlin. When the museum reopened its exhibition in the Humboldt Forum in the city center in September 2021, Ngonnso went on display with hundreds of other objects —including sculptures, masks, and drums—from various Cameroonian kingdoms and cultural groups that Germany took under its colonial rule there between 1884 to 1916.

It’s estimated that more than 40,000 Cameroonian objects are currently held in German museums, said Richard Tsogang Fossi, a postdoctoral researcher on Cameroonian cultural heritage at the Technische Universität Berlin. “Punitive expeditions are one of the biggest ways in which the objects were removed,” he said. Fossi is part of a Cameroonian-German research effort tracing lost Cameroonian objects in German collections. The staggering number excludes those objects in private homes and institutions not known to the researchers, he said.

The legacy of colonialism can still be felt in Cameroon today. After the German Empire was defeated in World War I, Cameroon was carved up by France and Great Britain. In 1960, the country became independent by merging the French- and English-speaking territories. Today, there are not only two official languages but also two legal and educational systems, under which the Anglophone minority often feel marginalized and suppressed. The discontentment has spiraled into a violent conflict between the Cameroonian military and Anglophone separatists since 2016.

Njobati grew up in the Anglophone region with her mother and grandfather, a Presbyterian pastor. “I would go to church with him, we’d worship together, and I did a lot of Christian activities.” She felt her Christian upbringing had disconnected her from her Nso roots. “I didn’t even know [Ngonnso] was the founder.”

When Njobati went to university in Yaounde, the capital of Cameroon located in the Francophone region, she felt her Anglophone background had made her unwelcomed. The experience prompted an identity crisis. She began to question — who am I without the cultures and systems left by European colonialism?

It turned out that her grandfather had similar regrets. As an only son, he was in succession to become a traditional leader tasked to govern the village compound, a collection of houses that serve as a community center but chose instead to answer his calling in Christianity. In his absence, the compound, where children were born and death were mourned, has fallen into disarray.

When Njobati told her grandfather about her plans to bring Ngonnso back, he was elated. “He would really like to see Ngonnso before he goes to eternity,” Njobati recalled him saying. She hopes that returning Ngonnso will also help bring unity for the Nso, which is one of the many communities in the Anglophone region suffering from the conflict.

For decades after the Ngonnso statue was taken, Nso people didn’t know where in Germany it was held. In the 1970s, a Nso scholar studying in that country chanced upon it in an exhibition at the Ethnological Museum, sparking the decades-long effort for its return. Nso people wrote letters to the German embassy, politicians, and the SPK, which refused restitution previously but said they were willing to lend the statue as a loan.

In March 2020, Njobati decided to go on offense. She launched the @BringBackNgonnso Twitter account, tweeting demands for Ngonnso’s restitution and tagging the German museum and its leaders. In September last year, she flew to Berlin to join other activists in protesting the Humboldt Forum’s opening, marching in front of the institute waving a handmade placard.

Then, she went inside the museum and saw Ngonnso for the first time.

“It was more of a spiritual encounter,” she said. “It was like I’m looking at my mother being helpless.”

Although the exhibition acknowledges that many objects were obtained under an unequal power relationship between Germany and Cameroon in the colonial period, Njobati found the label of the Ngonnso statue degrading.

“This sculpture may represent queen Ngonso’, who founded the Banso’ Kingdom,” the text says, using an alternative spelling of Ngonnso. “Kurt Pavel collected it when Germans first arrived in the kingdom’s capital, Kumbo. A few months later, when Pavel was on his way back to Berlin, another group of German soldiers provoked a war with the Banso’ kingdom.”

Though the museum questions Ngonnso’s role as founder and queen, citing a lack of historical documentation, for the Nso community, her status is indisputable, Njobati says. In addition, “Banso” is a term the German colonizers came up with to describe the Nso, and the word “collected” omits the contested history of how Pavel acquired the object. The text also does not inform visitors about Nso people’s decades-long quest to reclaim Ngonnso, which Njobati believes shows her people’s agency.

“It doesn’t give a true representation of history,” Njobati says. “It’s important for us as people to be able to tell our history in its entirety, with dignity and respect.”

Njobati’s campaign caught people’s attention. The famed Nigerian novelist, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, known for her writings on politics, race, and the African diaspora, mentioned the plight of Nso people when delivering a keynote speech at the Humboldt Forum’s opening ceremony.

“Ngonnso could not possibly have been obtained under benign circumstances, because why would you willingly give up your guidance spirit?” she said to a room of German politicians and cultural leaders. “A nation that believes in the rule of law cannot possibly be debating whether to return stolen goods. It just returns them.”

Njobati’s activism won Nso people a seat at the negotiation table in Berlin. Hermann Parzinger, the president of the SPK agreed to a dialogue, and Njobati was able to deliver an official restitution request signed by Fon Sehm Mbinglo I, the king of the Nso Kingdom. Parzinger’s reply: “Your letter is in good hands.”

Under pressure, the museum’s position began shifting. Three months after Njobati’s visit, the museum invited her for a workshop. It deepened the German side’s understanding of the statue’s importance to the Nso community, and the two sides exchanged knowledge of its acquisition history, said Verena Rodatus, a curator at the museum and contact person for the restitution negotiation.

The museum acknowledged there was a clear power imbalance between Pavel and the Nso community but added that the statue was not taken in violent injustice similar to the looting of the Benin Bronzes. When considering the restitution claim, Rodatus said the museum was also taking into account the object’s importance to the Nso community.

In the museum’s press release announcing its decision to return the statue, SPK president Hermann Parzinger said, “The decision makes it clear that the question of returning collection items from colonial contexts is not just a question of a context of injustice. The special—especially spiritual—significance of an object for its society of origin can also justify its return.”

The decision did not come soon enough for some. On the day of the Humboldt Forum opening, Njobati’s grandfather passed away. “He was the one person so deserving to see Ngonnso in his lifetime,” Njobati said. But she has no regrets about having stayed in Berlin to continue her activism.

“There are other people [who] have dedicated more than half of their lives fighting for the restitution of Ngonnso and ensuring that the people have a history that is befitting, decent, and a true representation of Nso land,” Njobati said. “These people also deserve to see Ngonnso before they die.”

This story has been updated to include information about SPK’s June 2022 decision to return Ngonnso to Cameroon.

This story originally ran in 2022; it has been updated for 2022.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook