Number One With A Bullet: The Rise of the Billboard Hot 100

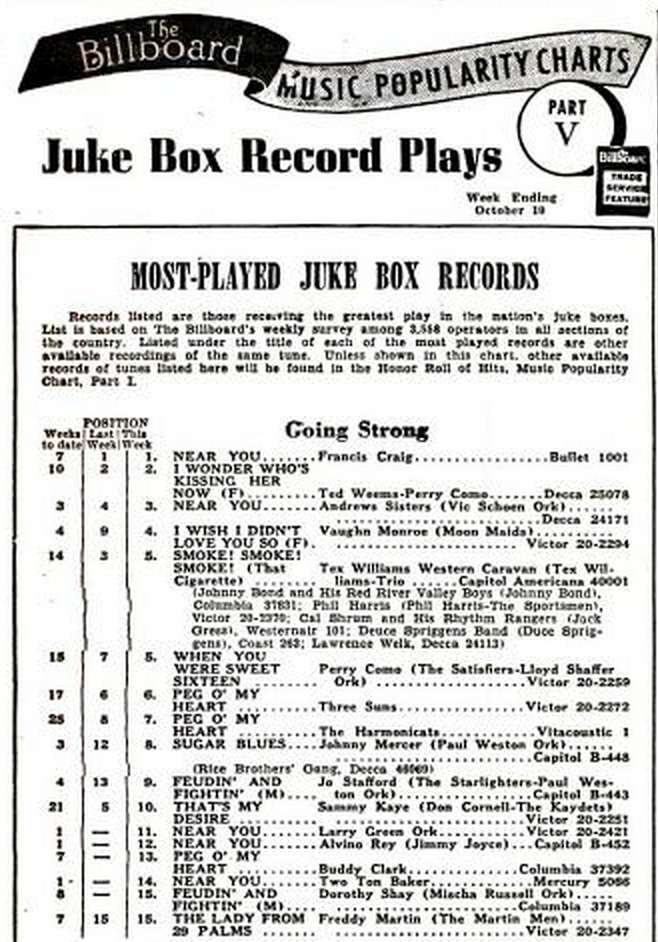

A 1947 Billboard Jukebox Chart—one step on the road to Hot 100 greatness. (Image: Billboard)

A 1947 Billboard Jukebox Chart—one step on the road to Hot 100 greatness. (Image: Billboard)

Say you want a three-minute break from work, something to help you kick back and forget about the world for two verses and three choruses. Alternatively, say you want a three-minute sum-up of the current zeitgeist, a way to figure out where our collective heads are at right now. Where do you go?

Why, the Billboard Hot 100, of course.

The Hot 100 serves many needs. Just as a Billboard-populated Top 40 is the easiest way to DJ a party with a variety of guests, a cheap jab at the moment’s #1 is the best way to criticize the entire United States at once. But how did the Hot 100, which turned 57 years old today, become America’s go-to weekly popularity contest?

Teen heartthrob Ricky Nelson, the first ever Hot 100 chart-topper. (Image: WikiCommons/Public Domain)

Teen heartthrob Ricky Nelson, the first ever Hot 100 chart-topper. (Image: WikiCommons/Public Domain)

As it turns out, the chart is just the most enduring of Billboard’s many attempts to bring information from one entertainment industry sector to the other. The magazine that now tells you that more people enjoyed Justin Bieber than Ed Sheeran that week started out as a circus trade rag in the 19th century, and spent the following decades undergoing more loop de loops and drops than a Skrillex song.

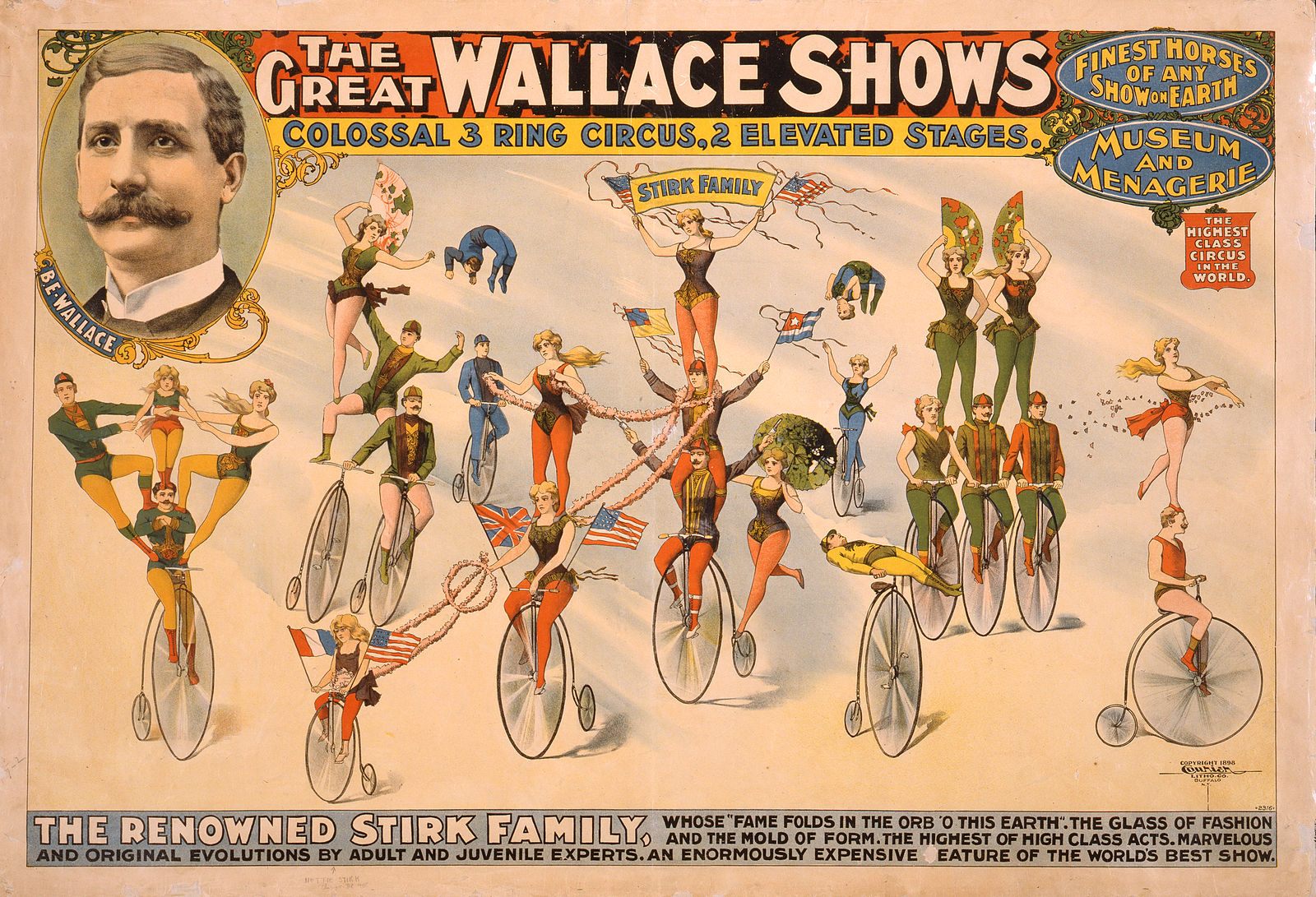

According to a history written by his grandson, Roger S. Littleford, Jr., the founder of Billboard, William H. “Bill” Donaldson, built the magazine to serve an entirely different need. Donaldson worked for the family business, a Newport, Kentucky-based lithography shop that churned out advertisements and posters for the circuses, fairs, and other traveling shows that criss-crossed the country. Donaldson realized that most of his clients—the managers and owners who ordered the posters, and, especially, the billstickers tasked with staying one step ahead of the shows and pasting the posters to every available surface—lacked permanent addresses, and thus were unable to communicate with each other.

A Donaldson Lithographing Co. circus advertisement, circa 1898. (Image: Library of Congress)

A Donaldson Lithographing Co. circus advertisement, circa 1898. (Image: Library of Congress)

In 1894, Donaldson started to spend his nights and weekends putting together Billboard Advertising, a trade publication dedicated to gathering all the news that might be relevant to his more itinerant peers. The first issue, published that November, had eight pages of relevant tidbits, laid out in columns like “Bill Room Gossip” and “The Indefatigable And Tireless Industry of the Bill Poster.” Now the “advertisers, poster printers, bill posters, advertising agents, and secretaries of fairs,” as the issue categorized them, could pick up a magazine at a newsstand anywhere in the country and know what to expect on the opposite coast.

Soon, thanks to a feature called the “Letter List,” readers could even use the magazine’s address as their own, and Billboard Advertising would forward them their mail or keep it for them at headquarters, free of charge, writes Ken Schlager in an official company history. Schlager describes the service as “a precursor of today’s E-mail,” and within 20 years, he says, “more than 42,000 performers, agents and other showmen” were taking advantage of the Letter List.

During this time, the magazine shortened its name to The Billboard, and lengthened itself to double its original eight pages. It now contained advertisements instead of advertising advice, and juicy show biz news instead of “poster-paste recipes,” Schlager writes. Donaldson also used his platform to advocate against both “filth” and censorship, hoping, presumably, that the entertainers would clean up their own acts.

The Billboard 1896 Christmas issue (left) and The Billboard’s Tenth Anniversary issue, from 1904 (right). (Photos: WikiCommons/Public Domain)

When Donaldson died in 1925—after a long retirement in a Florida home flanked by both Ringling Brothers—the magazine continued expanding along with the entertainment scene. At this point, concerts, movies and stage shows had largely outstripped circuses and whale shows in popularity and influence, and more and more of the magazine was dedicated to the exploits of singers and actors.

In January 1936, The Billboard published its first “Chart Line,” a tally of the songs played most often on three major radio networks. The first #1 was the jaunty “Stop, Look and Listen,” by Joe Venuti, the father of the jazz violin, featuring the prophetic lyrics “There’s no danger like the danger of a song and dance,” sung by Ruth Lee. By 1961, Billboard had dropped its carnival coverage entirely, fully seduced by the music business.

In the meantime, it was churning out chart after chart. The radio play list was soon joined by “Most Played in Juke Boxes,” “Harlem Hit Parade” (the first R&B chart), and “Hillbilly Records” (now called Country & Western). In July of 1940, Billboard added to their table stable with the intuitively named “List of Best Selling Retail Records,” considered the most direct ancestor of the Hot 100. The first retail champ was “I’ll Never Smile Again,” by Tommy Dorsey & His Orchestra and featuring Frank Sinatra and the Pied Pipers—the midcentury equivalent of that Calvin Harris/Taylor Swift collaboration we’re all waiting for.

Frank Sinatra in 1947, gearing up for a string of chart-toppers. (Photo: William P. Gottlieb/Library of Congress)

Frank Sinatra in 1947, gearing up for a string of chart-toppers. (Photo: William P. Gottlieb/Library of Congress)

After spending several decades compiling various one-variable charts, Billboard finally hit on their own #1 idea on August 4, 1958. They streamlined their most relevant lists—Best Sellers In Stores, Most Played By Jockeys, and Most Played In Jukeboxes—into one “main all-genre singles chart,” the Hot 100.

This was the “first true blend” of sales and plays, the secret sauce that reflected America’s actual favorites, says pop-chart columnist Chris Molanphy. The first song to be declared the official Hottest in the Nation was Ricky Nelson’s “Poor Little Fool,” the midtempo story of a heartbreaker who has the tables turned on him. (Crank that one up and imagine it wafting out of the open tops of countless Chevy Impalas.)

People loved having only one list to work with. Top 40 radio countdowns quickly aligned themselves with the first two-fifths of Billboard’s list (although some veered away again just as fast—the Hot 100 draws from a broad set of sounds, and some narrower radio stations got flack from rockist listeners who hated disco, or adults who hated 2 Live Crew).

The Hot 100 logo, blaring primary colors. (Image: WikiCommons/Public Domain)

The Hot 100 logo, blaring primary colors. (Image: WikiCommons/Public Domain)

The Hot 100’s ubiquity, simplicity, and constant shifting meant that people could talk about it with the excitement and savvy usually reserved for things like sports. It developed its own rituals—Casey Kasem’s smooth Sunday rundowns, the Year End charts and subcharts as the calendar turns. It has become immediate shorthand for success—no VH1 Behind the Music lacks a dramatic Hot 100 montage, and no diss track is complete without a swipe at the competition’s failure to chart.

It even launched a vocabulary: the phrase “number one with a bullet” refers to a Hot 100 innovation, a small symbol indicating that a song is on its way up. To be “number one with a bullet” means you’re at the top and still rising, thus not likely to vacate the penthouse anytime soon.

In the decades following its introduction, Billboard has tweaked the Hot 100’s formula continuously to keep up with the times. In 1959, jukebox plays were removed from the equation; in 2005, iTunes downloads were added to the fray, and streaming came on board in 2012. The biggest changes, such as the replacement of self-reported sales with more objective SoundScan data in 1991, caused seismic chart restructuring, catapulting acts as different as NWA and Garth Brooks to the top. These days, to reach #1 status, you have to perform well in three areas: sales, radio airplay, and online streaming. In other words, people have to like your stuff enough to want to hear it at home, in the car, and on the computer.

The once-mighty jukebox, no longer the arbiter of hotness. (Photo: Kenny Louie/Flickr)

The once-mighty jukebox, no longer the arbiter of hotness. (Photo: Kenny Louie/Flickr)

The latest song to hit this trifecta—the era-definer for this week—is “Cheerleader,” which uses smooth vocals and bubbly horns to convey the happiness of a man who has finally found the right woman. The song has been kicking around in one form or another since 2012, when singer OMI released it in his home country, Jamaica. After an American producer discovered the song in 2014, he commissioned a remix by German producer Felix Jaehn. This radio edit, itself an internationally tweaked supersong, hit all the right buttons and has been at the top for three weeks.

In the upcoming decades, when people look back and try to understand August 4, 2015, they’ll have “Cheerleader” to guide them. And in this way, Billboard continues its original mission—helping people keep track of the evolving American circus.\

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook