The Lost Newspaper Archives of Black Chicago Are Now at Your Fingertips

The Obsidian Collection and Google are bringing historic African-American media outlets online.

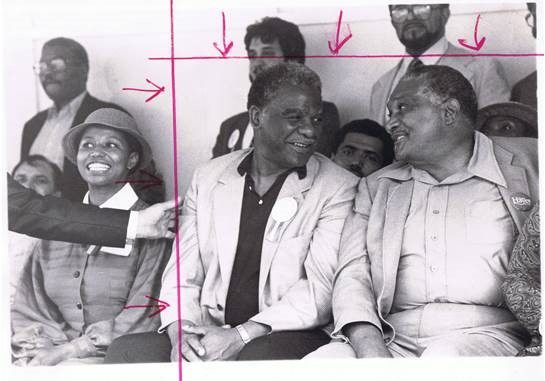

In 1983, Harold Washington, Chicago’s first black mayor, spotted Congressional candidate Charles Hayes at a city event. When the two sat down to talk political strategy, a photographer from the Chicago Defender was on hand to capture the moment.

Later, when an editor cropped the photo for the paper, they cut out a smiling young woman sitting to Washington’s right. About 16 years later, the editor probably regretted it: That woman was Carol Moseley Braun, who in 1992 became the first African-American woman ever elected to the U.S. Senate.

This is just one of the many surprising stories hidden in the photo archives of the Defender, the pioneering newspaper that has been covering black life in America since 1905. Thanks to a new collaboration between the Obsidian Collection and Google Arts & Culture, you can now get an inside look at everything from the heavyweight champ Joe Louis’s signature milk brand to the Defender’s own printing presses—and, in certain cases, their editing processes, too.

The Obsidian Collection is an archival project focused on digitizing African-American newspapers. Angela Ford, the Collection’s founder and director, originally started it for personal reasons. Her grandmother moved to Chicago from Oklahoma during the Great Migration. “She had a charm school and a line of cosmetics in the ’50s,” Ford says, and was often written about in the Defender.

When her grandmother passed away, Ford started looking for copies of some of those articles, and learned that the paper’s archives were in bad shape. To make matters worse, when she told her son about newsworthy things that had happened when she was growing up, he often found there was no record of those, either. “He’d go to Google it, and it wasn’t there,” she says. “I thought, ‘Wait, what?… My past was disintegrating. That’s how I got involved: to save black history and to save myself.”

Ford managed to stabilize the Defender’s archives, which contained 250,000 photos—more than twice as many as anyone expected. After that, she says, “I learned a lot of the black newspapers were in a similar position.” Encouraged by her son, she started to digitize them, too. Last year, she started speaking with Google Arts & Culture, and the platform posted eight sets of Obsidian Collection Archives photographs earlier this week. Many more will follow, Ford says, from all different newspapers and regions.

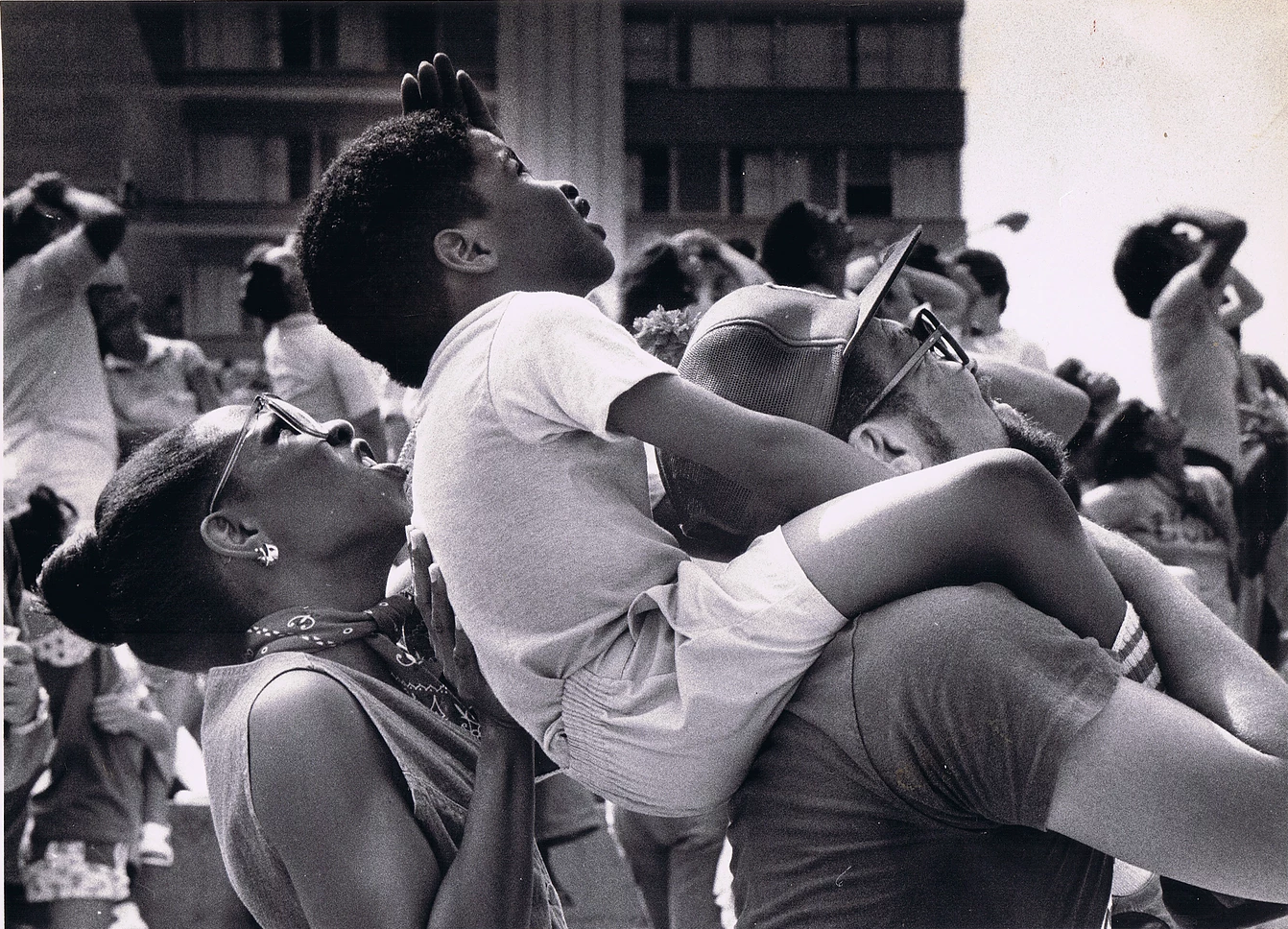

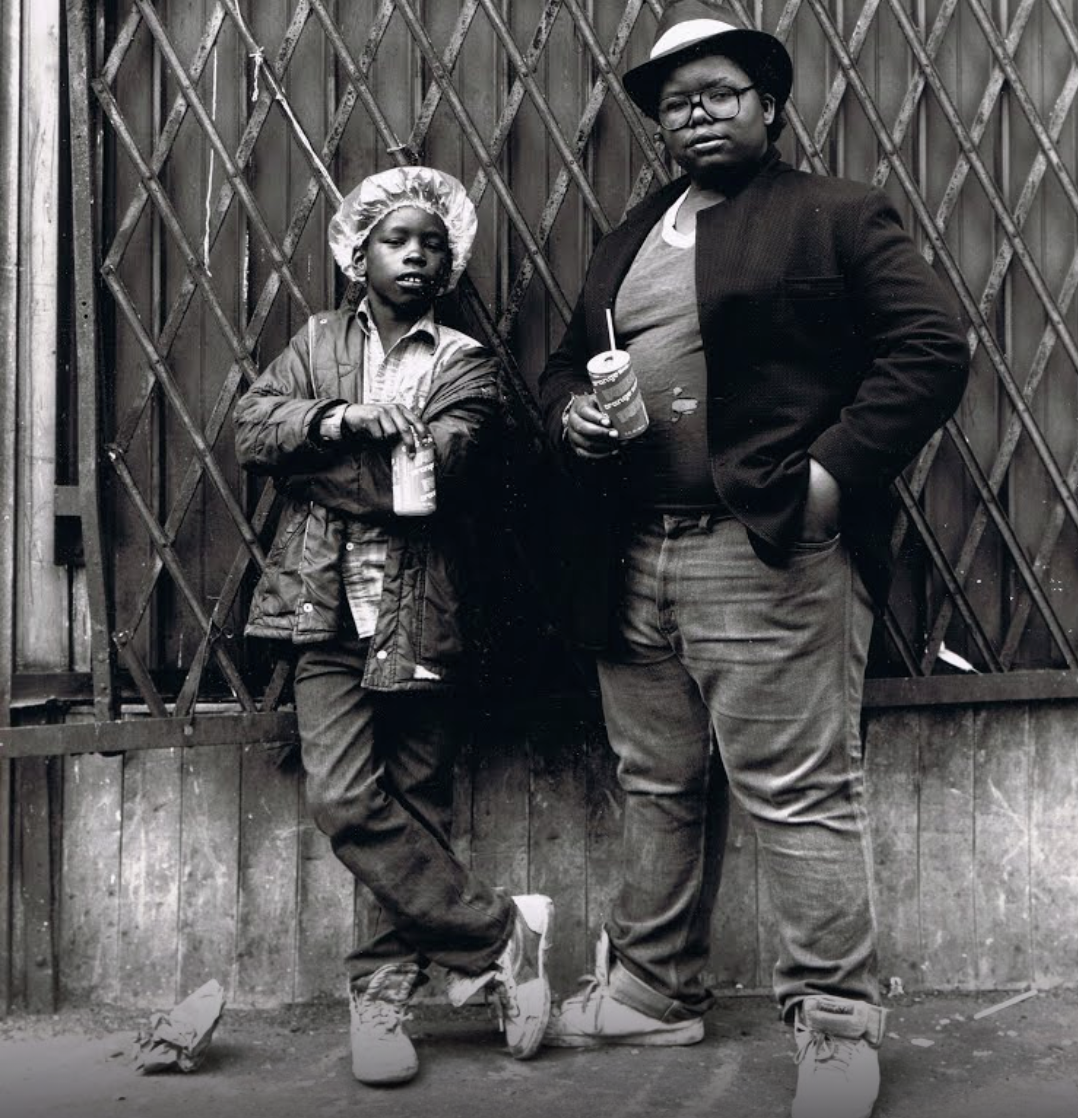

The current sets run the gamut, from a photoessay about the pioneeering aviator Fred Hutcherson, Jr. to an inside look at the Chicago Housewares Show of 1959, hosted by the Defender. One of Ford’s favorites is “Outdoors in Chicago,” a set of photographs from the late 1970s and early 1980s that she says remind her of summer days with her son and his friends.

“It really does speak to the black boy joy that I see every day,” she says. “That narrative has not been illustrated in today’s mainstream media at all… The mainstream narrative is that we’re either victims, or we’re violent. So we’re not doing that. We’re doing everything else.”

Ford hopes that digitizing these images will encourage people to make the stories a part of their everyday lives. “It’s the new way to visit a museum,” she says. “You will visit the Google Arts & Culture Obsidian Collection when you’re waiting for the doctor’s office or in line at the grocery store. It can take the edge off.”

“If it does just that—and expands your mind past what you thought you knew—I consider that a victory.”

To see more photos from the Defender’s archive, visit the Google Arts & Culture Obsidian Collection homepage.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook