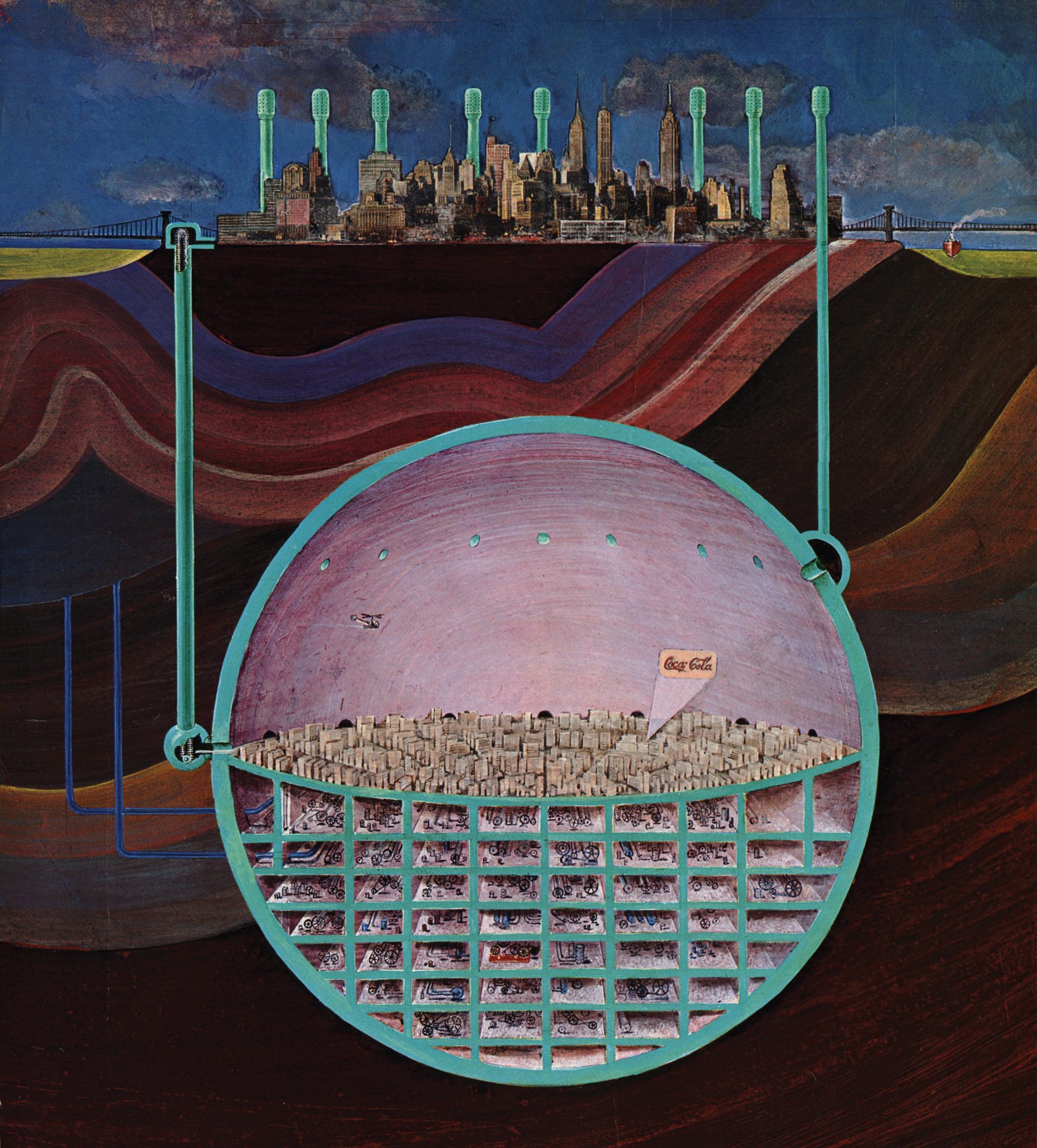

One Architect’s Spectacular Vision for a Spherical Subterranean City

New Yorkers would weather nuclear attack in an underground metropolis.

Imagine if underneath major metropolises there were spherical nuclear shelters that contained more cities—mini-Manhattans buried thousands of feet in the ground.

In the 1960s, architect and city planner Oscar Newman rendered what such a fantasy would look like beneath New York City.

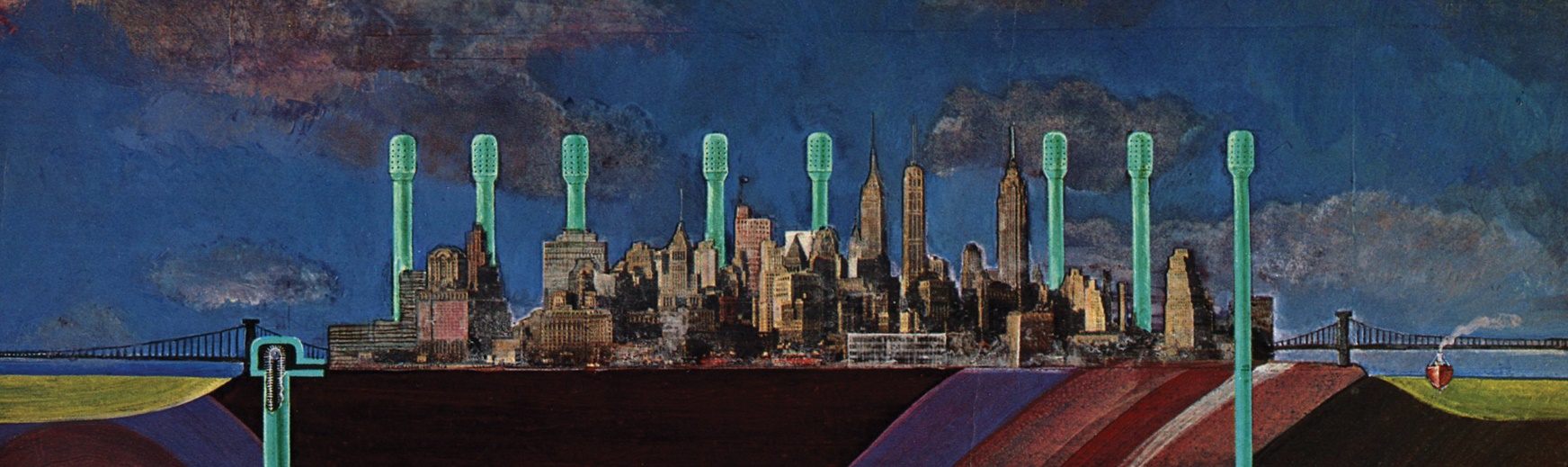

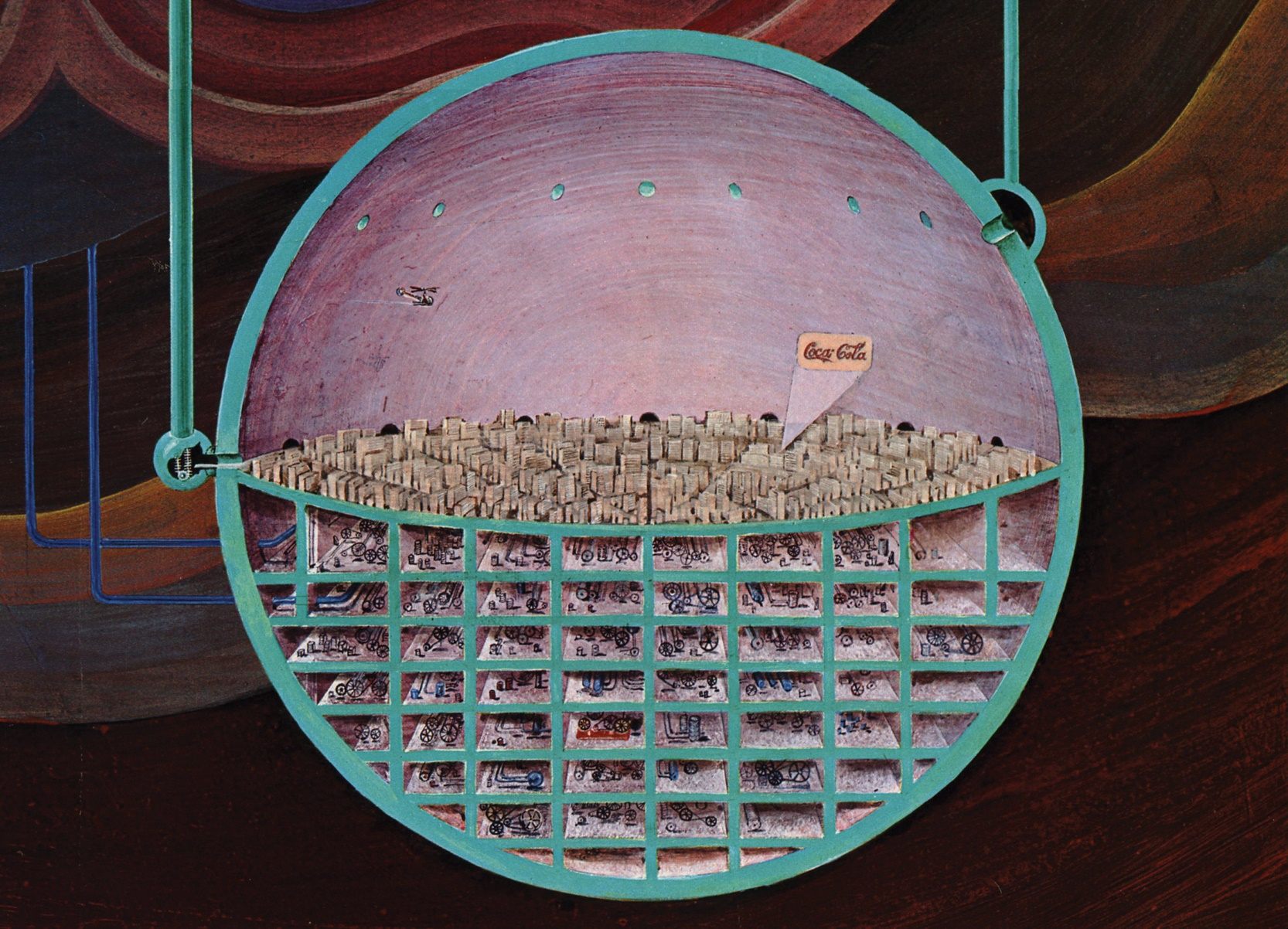

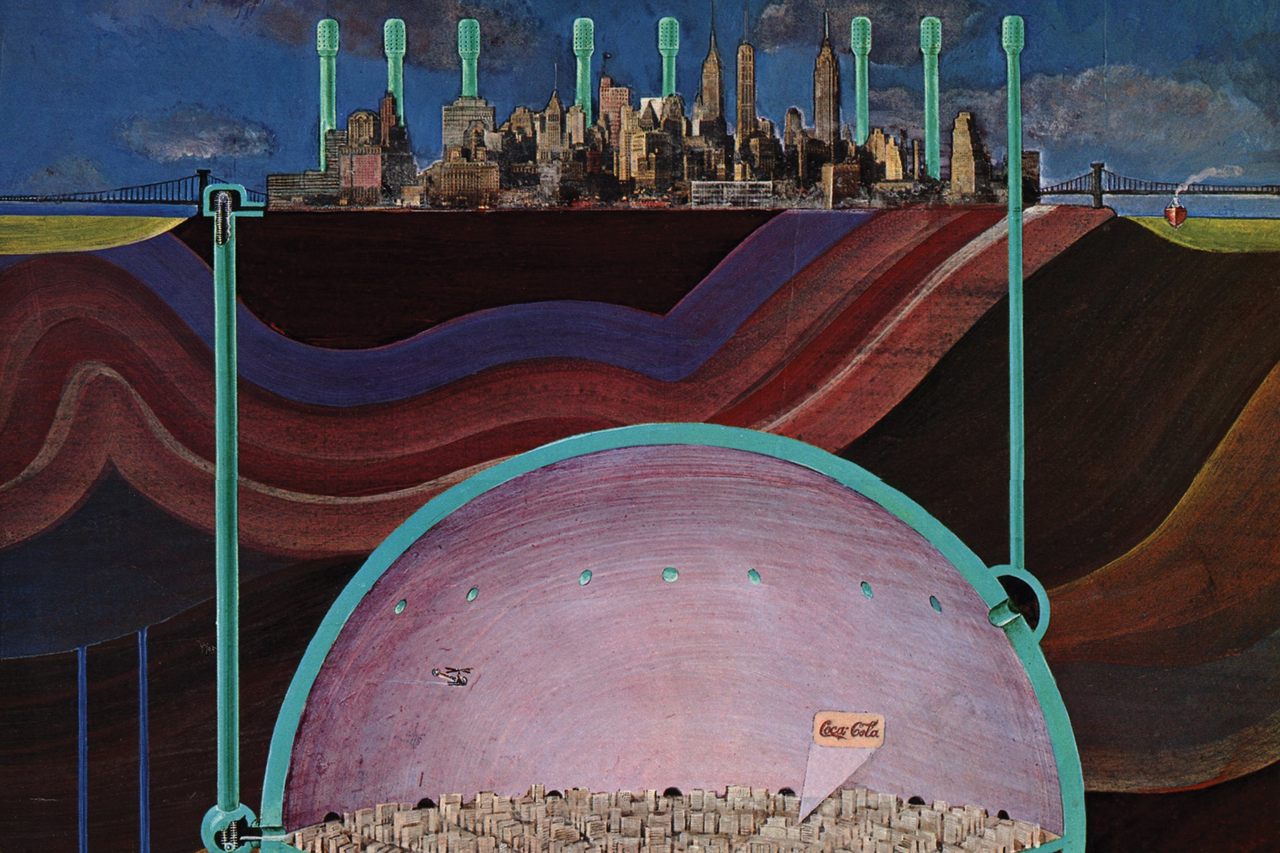

In the December 1969 issue of Esquire, Newman published a peculiar map of a colossal nuclear city deep below New York. The purely imaginary proposal, titled Plan for an underground nuclear shelter, was complete with an entire labyrinth of buildings encased in a metal sphere along with a helicopter, Coca-Cola ad, and air filters.

Newman’s take on the limited space of New York City and the atomic world of the 1960s gives “the opportunity to explore the notion of living in this entirely different environment,” says Katharine Harmon, author of You Are Here: NYC: Mapping the Soul of the City.

The vibrant, sci-fi city Newman depicted does not follow traditional cartographic conventions. Plan for an underground nuclear shelter falls under what Harmon calls “creative cartography.”

“This encompasses innovative mapping and mapping of the imagination, and includes ‘maps’ that can be called illustrations—any visual that navigates a place or idea or state of mind,” she says. “I would classify Newman’s map as pictorial, and illustrating a fantastical idea.”

During the 1960s, the Cold War and prospect of nuclear weapons being deployed served as alarming inspiration for artists and writers. Plots in science fiction and artistic renderings featured post-nuclear apocalyptic universes, emulating real fears within society. Newman was no different. The map was inspired after he had heard about the 1962 Storax Sedan nuclear test—a shallow underground mining test that created a massive crater in Nevada. The crater is the largest man-made crater in the United States.

Newman also had intimate knowledge of the layout and architectural facets of New York. In 1972, he published the book Defensible Space in which he used New York as a case study to examine crime rates in high-rise apartment buildings and housing projects. He imagined how a subterranean miniature city under New York might look and function if giant chunks of earth were cleared using advanced nuclear equipment.

The nuclear shelter is a miniature copy of the city above it. The top half of the sphere would be inhabitable, structured to support streets and buildings that appear to arranged radially. Beneath the mini-city is a grid network that provides energy and allows the city to function. A small helicopter can be seen hovering in the upper left corner of the sphere, perhaps monitoring the city from above.

Harmon appreciates the “wackiness” of the nuanced details in the map, such as the lone projected Coca-Cola ad on the ceiling of the sphere and the Q-tip-shaped air filters. The dome has a series of connected tubes that project the filters above ground so that people below can get fresh air—the blue-green structures new additions to Manhattan’s original skyline.

Circulating fresh air into the underground city was one of Newman’s primary concerns, as he wrote: “The real problem … in an underground city would be lack of view and fresh air, but consider its easy access to the surface and the fact that, even as things are, our air should be filtered and what most of us see from our windows is someone else’s wall.”

It’s clear that such a proposal is implausible, and it’s likely that Newman drew the map for Esquire as a riff or joke on his urban planning, says Harmon. John Ptak, blogger of JF Ptak Science Books, calls it “a terrifically bad idea.” On his blog, Ptak reviewed the impracticalities of pursuing Newman’s plan:

“The author of this plan speculated on building this spherical city in Manhattan bedrock—a structure which so far as I can determine would have a volume of 1.2 cubic miles (5 km3) with its top beginning some 1,200 feet under Times Square. It’s an impressive hole “just” to dig—it would be a goodly chunk of the volume of Lake Mead. And it would make the world’s largest man-made hole—the Bingham Copper Mine in Utah—seem like the very beginning efforts to digging this beast out to begin with.”

Newman did not detail what exactly the cities would be used for: alleviating overcrowding; alternative space in the event of nuclear war; or luxury futuristic get-away. While Newman’s atomic city map may be categorized as sci-fi fantasy, it does inform us of 1960s nuclear culture.

“Maps enable us to explore other territories, including products of other imaginations,” says Harmon. “Newman uses illustration skills to illuminate a concept both ‘practical’ (a solution for protecting a large population from nuclear war) and wildly impractical (nuclear detonations as the means for creating the cavity), serious and whimsical.”

Map Monday highlights interesting and unusual cartographic pursuits from around the world and through time. Read more Map Monday posts.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook