Exit Interview: Scott Kelly, an Astronaut Who Spent a Year in Space

It’s very easy to lose things on the International Space Station.

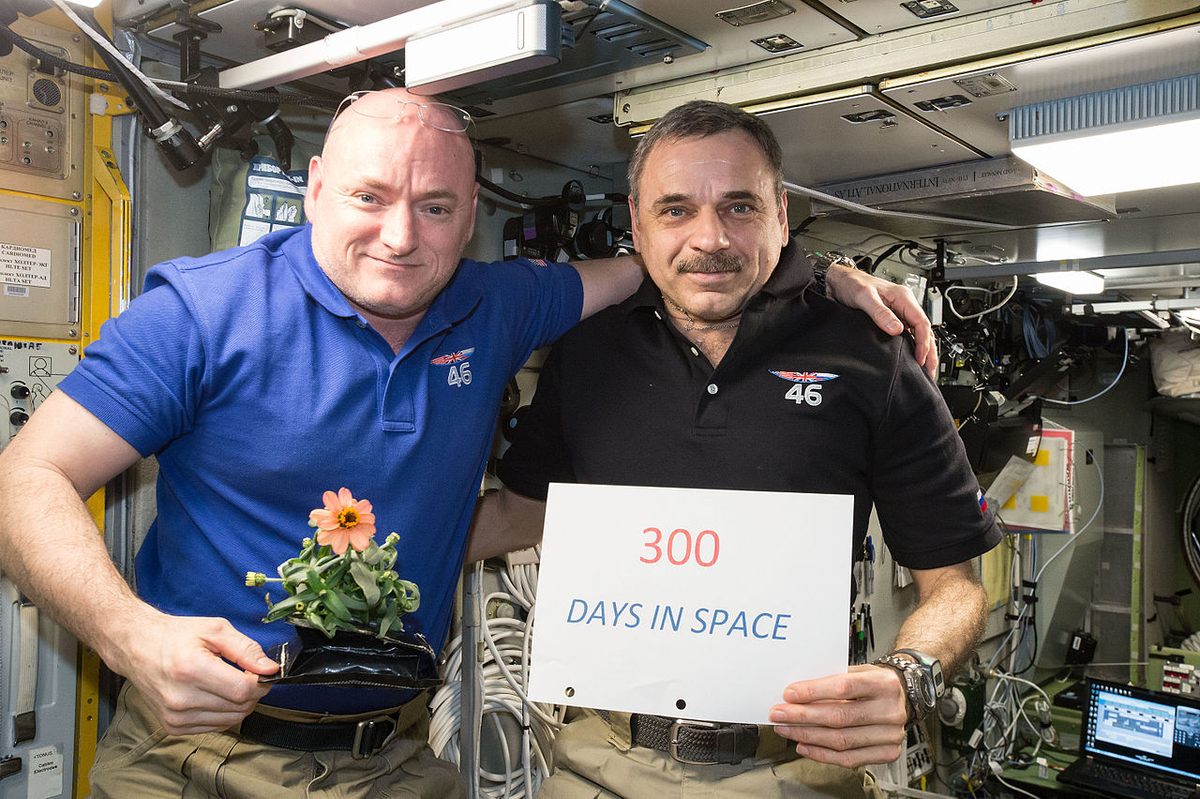

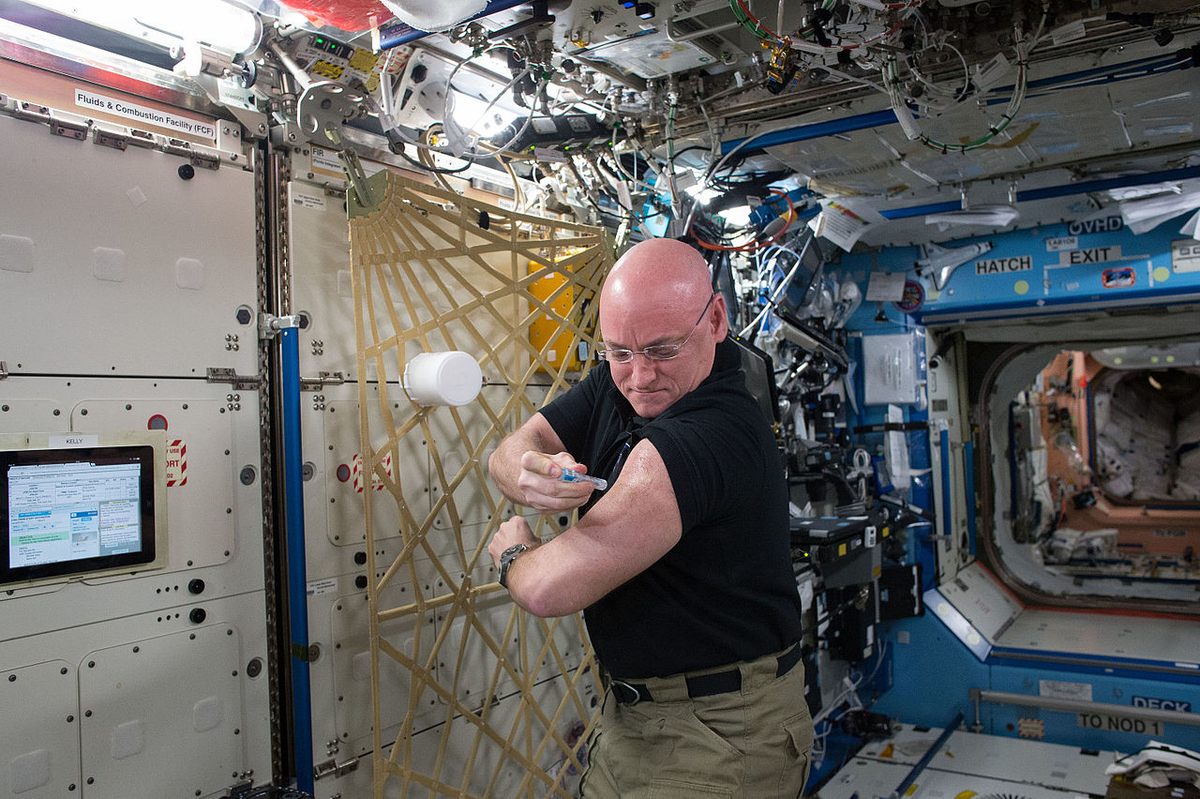

Being an astronaut is not all zero-gravity gymnastics and big blue marble flyovers. There’s also all the time spent repairing the urine collector and hunting for lost screws. Scott Kelly’s delightful new memoir, Endurance: A Year in Space, A Lifetime of Discovery, chronicles the mundane, frustrating, and surprisingly funny reality of life on the International Space Station (ISS). Endurance recounts his year up there—including the Sisyphean struggles to fix the urine collector—his unlikely career as an astronaut, and his partnership with identical twin brother and fellow astronaut Mark Kelly. Kelly retired as an astronaut in 2016, shortly after the end of his year-long mission, but NASA continues to monitor his health. They’re examining specifically how his year in space affected Scott compared to his ground-bound twin, Mark. Atlas Obscura CEO David Plotz interviewed Kelly on his book tour in Washington, D.C. He was accompanied by his fiancée Amiko Kauderer, who makes a cameo.

What does space smell like?

It smells different to different people. Some people say it smells sweet. To me it smells like burnt metal, like if you took a blowtorch to some steel or something. Maybe like welding or sparklers? On like the Fourth of July? A very distinct smell. We need to get some sparklers to check it out because I haven’t smelled a sparkler in a while.

I need to do research a little bit on it, but clearly it’s not the smell of nothing, because nothing wouldn’t have a smell. But it’s the smell of whatever the materials are on the outside of the space station that are in vacuum, exposed to the sun. Some people say it’s the smell of atomic oxygen, which is O instead of O2. I guess there’s atomic oxygen in small quantities outside the space station. I personally just think it’s off-gassing of the stuff that’s exposed to vacuum for long periods of time.

What’s the favorite thing that you’ve learned about how your year in space changed your health?

It made me smarter and more handsome than my brother Mark [laughs]. With the twin study, particularly, there was a bunch of experiments that were genetic-based. And there are these things called telomeres, which are the ends of our chromosomes, and the length and quality of them are indications of our physical age. The hypothesis was that with me being in space, and the radiation, and the microgravity, maybe the stress of living there for a long period of time, my telomeres would get shorter and basically older compared to Mark’s. What they found is that mine got better. So physically I got a little younger than he is, and then once I got back they kind of went back to their normal, preflight condition.

Is there any evidence that astronauts live longer?

Recently I was told by someone in our medical department at NASA that we went over the point of statistical significance for cancer in astronauts and people that have flown in space—so, more than average. But I think, subjectively speaking, just my observation, as these Apollo guys die—a lot of them are dying in their 80s. So that’s pretty good, if you’re making it to your mid-80s. I don’t know if anyone’s really looking at this in fine detail, but on one hand you’re told, “Yeah, we get cancer more,” on the other it seems to me like these guys are living pretty long lives, so …

When you’re up there on the ISS, arguably you’re the most expensive human being on the planet except the president. The amount of resources being spent to keep you alive are enormous. Did that weigh on you at all?

Never even thought about that. No. Never considered it. I appreciated the effort that people went through to make sure you’re safe, and are taken care of and supported while you’re there, but I never considered the cost of it.

Did it feel like, “Man, I gotta work all the time”?

I think some people feel that way. I kind of felt that way on my [first, six-month ISS mission]. But having flown for six months, and then a few years later flying for a year, I realized I couldn’t do that. So I definitely had to pace myself throughout the course of the year. I mean, my goal is to get to the end with as much energy and enthusiasm as I had at the beginning, and I think I succeeded. I mean, I wanted to come home, but I could have stayed if there was a valid reason. It wasn’t like I was climbing the walls to get out of there.

What were some of the tricks or mechanisms you used to make sure, “Oh, I’m going to maintain that energy”?

One is that you can’t do everything perfectly. I mean, the stuff that needs to be done perfectly you have to do perfectly, but everything else? Sometimes better is the enemy of good enough. And, having that kind of a mindset I think was helpful. In some ways I think that having some undiagnosed ADD can be helpful because it’s easy to ignore certain things that might not be as important, and then hyper-focus when it is. And I’ve seen some of my colleagues in the past get kind of spooled up around trying to make everything perfect, and you can’t do everything perfect for six months. Your timeline is so constrained that sometimes you have a choice—get through stuff quickly to then move on to the next thing, or not get half the stuff done you were supposed to do that day.

One of the things I loved in the book is the account of your repairs of various things. Is it maddening to think that these things, which would probably take you ten minutes on Earth, become an elaborate process when you’re in space?

I wouldn’t say it’s maddening because it is what it is, right? Everything floats, which makes everything, with the exception of two things, harder to do.

Those two things being …

Moving stuff that’s heavy.

And then getting behind your entertainment system to hook up the VCR is easier, because you don’t have to do it like this [sits up straight], you can float upside down and get into whatever body position is most efficient. Everything else is harder to do. The more time you spend in space, the better you get at it and you will operate more efficiently. But repairing hardware when you can’t put your tools down! Imagine working on your car if you’re an auto mechanic and you can’t put anything down! You can’t put a bolt down, a washer, a wrench. You gotta do something with it. Stick it in your pocket, stick it on a piece of tape, piece of Velcro. It makes stuff much more challenging.

And when you’re outside the station on your spacewalks, it’s like that times 10.

It’s even more significant because there, if you lose something not only do you not ever find it again, but it is a piece of orbital debris. So, an orbit later whatever you lost is potentially going to hit you.

Did you ever lose anything outside?

No. Nope. I never lost anything. I could’ve. I always say, never criticize somebody because as soon as you do that, that’s going to be you.

Did you lose anything in the station?

All kinds of stuff! One of the last things I remember losing was this fancy, 3-D printed cover for some experiment. It was for the camera and I turn around and the thing’s gone, and they didn’t have a spare. I’ve got to see if they’ve found that thing yet.

Oh, yeah. We lost a bag of screws and washers one time. We were getting ready to repair the $10,000,000 space suit. We’re getting all the stuff ready, and we’re like, “What happened to the big bag of screws and washers?” and it was gone. And I wasn’t even sure, I was almost certain that we never even had it because it was not there. And then I looked for days for it because we were going to work on the suit the next week, and then we needed to replace the pump separator, and it’s very, very detailed. It’s almost like doing heart surgery on a space suit. Little tiny screws and the stuff doesn’t fit together. It was never designed to be repaired in space.

We lost the screws and after looking for a few days we finally gave up, and I was almost convinced that we had never even had them. And then the ground was telling us, “Okay, well you might be able to find some similar screws here and washers here,” and kind of piecemeal it together. And we were able to sort of get the stuff we needed to work on the suit. The morning we were going to get started, the way it happened was the weirdest thing. I was in one module, and I look over, on the other side, over by the weightlifting machine, I just saw this little corner of tape that looked like it was attached to a plastic bag—just poking out. I floated over there and it was a big bag of screws. Right before we got started working on it! Crazy.

Usually if you lose something, the good way to find things—besides going to the vent that you think has the most suction—is turning upside down. It’s like a completely new perspective on your environment. Especially when you haven’t been in space for a very long time, if you turn upside down it’s almost like you’re in a different place.

When you’re on the U.S. side of the ISS and the Russians are on their side, how much interaction is there, day-to-day?

They work predominantly in the Russian segment and have their meals there, so during waking hours, they’re generally on their side, we’re generally on our side. You interact, you go down there, you chat with them, you come back, you might perform some kind of experiments, they might do a little thing in our space station, but it’s what we refer to as “segmented ops.” We do our own thing, come together in the evenings for social things. The Russians also used one of our exercise machine devices, the weightlifting thing. So we see them when they’re exercising. Sometimes a toilet breaks and you have to, you know, use the other guy’s toilet. But generally, yeah, U.S. and other partners on one side and the Russians on the other.

Does it feel like you’re all in it together?

Yes! Absolutely. We actually do some things to help each other that we don’t even share with the ground because then it creates like bureaucratic … issues for them to deal with. I’ve been asked to help fix some of their hardware, their treadmill one time. We help each other getting trash off the space station without telling the folks in Houston. I call it the “trash fairy.” One night on my previous flight, there was a Russian vehicle that was leaving the next day, and I wake up in the morning and 12 of our giant trash bags have just vanished. Without us even asking. The trash fairy must’ve come overnight!

Tell me about CO2 levels and how they affected you.

So when the CO2 is at our normal low levels on the space station, it’s 10 times what it is on Earth. And everyone is affected differently. Certain people react more to it than others. It made me really congested, it burned my eyes. I mean, I used Sudafed and Afrin almost for an entire year.

You’re not supposed to use Afrin for an entire year!

I know, right? I mean I wouldn’t use it every day, but I would use it when I had to. It’s not like I got addicted, but I would use a little bit of it here and there when the CO2 was high. It also causes kind of a fogginess of thought, and I think it affects your cognitive ability, your ability to focus. I don’t know if that’s because there’s some kind of physiological thing going on with your brain or because you don’t feel good, but it’s hard to focus. Like when you’re sick, it’s hard to pay attention.

Did your fellow astronauts and cosmonauts report similar feelings?

Yes and no. I think there are probably people who are less affected. There are probably also people that don’t want to acknowledge to the ground that it is bothering them, because they think they’ll be looked down upon. I was going to be there for so long that I felt like I wanted to elevate it as an issue. If there’s something we can do to make the situation better while I was there, I wanted to do that, and also for the people who will come after me. The Russians say that it should be high because it helps protect you from radiation, but I think they just want to stop people complaining.

What was the worst thing you ate in space?

Anything with the name teriyaki in it was bad. Something about teriyaki in space. Terrible.

The best?

There is a granola and milk thing I would eat here if I could have it. The irradiated barbecued beef was pretty good.

What bothered me more than the food was that you ate just floating there. You don’t have a chair to sit in. You don’t have a table. There’s no silverware and no plate. And maybe your spoon floats away and you lose it and you want to cry because that was your favorite spoon. And your backup spoon is half as long, so every time you dig it in, you get a little food on your hands.

What did you miss the least when you were in space?

Traffic on I-45 in Houston. I was hoping I would go to space and come back a year later and they would be done with all the repair work. But no.

What was your favorite place on Earth to fly over?

The Bahamas are pretty beautiful. It’s funny that the places where humans don’t live—water and deserts—are most beautiful. The colors where people live generally didn’t look all that appealing. Something about how the light reflects out to space is not that great. Aliens would definitely land in the Bahamas.

One of the cool places I want to go is—and this is from being in space and looking at it—is these little lakes north of the Himalayas. Little tiny lakes and they’re all different colors.

What can you see with your naked eye?

You can see runways. You can see big cities, and cities focus your attention to that area, and then you can see a runway. You can also see contrails from airplanes. That’s about it. You can’t see the Great Wall of China. You might be able to, but it’s made by the same material that’s around that area, so it blends in.

With a long lens, though, you can see a car. I was trying to get a picture of [my fiancée] Amiko. She was going to put a white sheet on our hot tub and lie there in black clothes, and I felt like I could possibly get a picture of her. But we never did it.

[Amiko Kauderer]: A couple times I was like, “Okay, I’m going to go take a lunch break right now!” and then I’d race home from work, and get out of my clothes, put all black on, and throw out the sheets. And I’m just lying out there with the phone, “Can you see me yet? Can you see me?” “No, I think I missed you.”

Always a cloud in the way or something.

Tell me about the gorilla suit.

My brother says to me, “I’m sending you a gorilla suit.” I’m like, “Why do I need a gorilla suit?” He’s like, “There’s never been a gorilla suit in space. Never been a gorilla in space. Everyone loves a gorilla.” Eventually I decided there was a good reason to have it up there. I was a kid who couldn’t pay attention in school, and even now as an astronaut I talk to kids sometimes and there’s always that kid like me—doesn’t matter if there’s an astronaut talking to your class—he’s looking out the window, just not paying attention. You throw a video of a gorilla floating around in space, you can’t not look at that.

Needed a little humor to lighten up a #YearInSpace. Go big, or go home. I think I’ll do both. #SpaceApehttps://t.co/Ift8VdDR4C

— Scott Kelly (@StationCDRKelly) February 23, 2016

Is there anything you left up in space that you’re like, “Damn, I wish I brought it back”?

No, no. My brother would send me stuff that would be so stupid, just to irritate me. If he was somewhere he would go into some gift shop and get a little palm tree with some seashells, “Welcome to Florida” or something. And then I’d have this thing I have to do something with for a while.

Was he just messing with you?

Yeah.

Is it true that being in space, and looking at the big blue marble, gives you a sense of perspective on the world?

Yeah. Astronauts who have seen Earth from space report about this orbital perspective. I’ve heard it called the “overview effect.” For me, it was a couple things. One is, the environment and atmosphere look very fragile, very thin. It’s like a contact lens over the surface of your eyeball, and you think, “Wow, that’s something that we need to take care of.” You see pollution over certain parts of the Earth. China and India are almost always covered in pollution. The United States is one of the biggest polluters in the world, but it’s not the kind you can see. So it makes you think that we need to do a better job taking care of our environment.

Rainforests—you see deforestation over long periods of time. I flew my first flight in 1999 … definitely a change when you look 17 years later. And when you look at the Earth, you don’t see political borders. Now, at night you do, but during the day you don’t.

The Earth, despite the pollution in some places, generally looks really beautiful and inviting, but when you hear the news it’s not that beautiful and that inviting. I remember there were days in the summer, when I first got up there, when we had some beautiful weather over the Mediterranean. It was just incredibly blue, and the contrast with the desert was amazing. Then you sit down and watch the news in the evening, and you see that, on those same shores, these little kids are washing up on the beaches dead. And you think, “You know, why can’t somebody do something about that?”

So it makes you think that we’re all in this together. We are all part of the same crew, spaceship Earth, flying through space.

Does that wear off when you’re back?

No, I don’t think so. I still kind of feel that way. The key is doing something about it, right? That’s always the hard part.

Space is a cold, inhospitable, radiation-infested, barren vacuum. Will there be space tourism? Will we be able to settle on the Moon or Mars, or is it just too inhospitable and too vicious?

I think for most people there will be some form of it. The hardcore person might be the one that moves to Mars someday. Some people say we need to make Mars like Earth because eventually we will have to leave Earth because we’re going to destroy it. I think it’s going to be a whole lot easier to make this planet continue to be habitable than it will be ever to make Mars like Earth. But as societies continue to expand, it’s important to move beyond where you are, grow the economy, grow civilization. At some point people will be moving to Mars to live in a habitat and, maybe a thousand years from now, there’ll be a way to create an atmosphere on Mars. I don’t know. But I think there’ll be experiences for everyone, from flying in space on a suborbital flight for seven minutes of microgravity, and looking out at the curvature of the Earth, all the way to living in space for long periods of time or going to Mars.

Does the astronaut selection committee ever make a mistake?

Oh yeah, absolutely. I went up on my STS-118 flight and I was a commander of the space station or Space Shuttle. I had to go up there and counsel one of the guys. I was directed to talk to him about, “Hey, this ain’t working out too well.” I don’t want to say who it was.

Okay, I’m going to ask you one more question. My colleagues forced me to say that I would ask it to you. I’m sure you’re not going answer it, but if you answer it, it’d be awesome.

Okay.

Do astronauts masturbate in space?

Ha! That’s funny [laughs]. I’ve never been asked that one. I’ve been asked if anyone has sex up there [laughs] …

Can I take the fifth? [laughs]

Yeah, you can take the fifth!

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook