Seeking the Last Remnants of South Dakota’s ‘Divorce Colony’

How Sioux Falls became a controversial Gilded Age “Mecca for the mismated.”

The stone clock tower of the old Minnehaha County courthouse looms over the low-slung landscape of Sioux Falls. It’s no longer the tallest building in South Dakota’s largest city, but it remains the most recognizable one, and there are still some people who recall when it was the administrative hub of the region, from the 1890s through the 1950s. “A lot of people remember coming here when it was still a functioning courthouse,” says local historian Shelly Sjovold, “but most of the time it was when they were very young, and they first got their drivers’ licenses. That’s where you did things like that.”

I visited the old courthouse on a very different errand: to research my new book The Divorce Colony: How Women Revolutionized Marriage and Found Freedom on the American Frontier. I was looking for any evidence that still remains in the city from the time when Sioux Falls was home to scores of unhappy spouses, many of whom had traveled more than a thousand miles to end their marriages. I was looking for the remnants of what 19th-century journalists came to call the “divorce colony.”

Divorce was the culture war of turn-of-the-century United States, and laws varied wildly from state to state. In South Carolina, there were no provisions for divorce at all. In New York, adultery was the only legal justification. South Dakota, on the other hand, had some of the most lenient laws in the country and one of the shortest residency requirements. In 1891, when prominent East Coast socialites began to arrive, one had to live in the young state for just three months to fall under the jurisdiction of its courts—a holdover from territorial days when the government was eager to welcome arriving white settlers. Sioux Falls, served by five railway lines and the Cataract House, the nicest hotel for hundreds of miles, became a “Mecca for the mismated,” according to the Pittsburgh Daily Post. It was the setting for soap opera–worthy plots that played out on the nation’s front pages—and a flashpoint in the country’s fiery debate over who should be allowed to end a marriage and why.

The Sioux Falls divorce colony marked a real and important turning point in the country’s social history, but, “I’m not going to say it’s viewed as folklore, but it is sort of treated like that, a little bit,” says Sjovold, collections assistant at the Siouxland Heritage Museums. “A lot of people know we were called that, but they don’t really know the whole story.”

Part of that story took place in the old courthouse, a beautiful building of locally quarried quartzite designed by famed local architect W.L. Dow. Many landmarks from the era of the divorce colony have been erased—the Cataract House hotel where the most notable divorce colonists lived was demolished in the 1970s and the Edmison-Jameson Block, home to many of the city’s lawyers, met the same fate—but preservationists rescued the old courthouse from the wrecking ball and a future as a parking lot. Today it is a museum, filled with photographs and artifacts of life in the region. My destination was the second-floor courtroom, a towering space with a mezzanine outfitted with theater-style seating. This, in the early 1890s, was where you would have come to watch the latest scandalous public divorce trial—and the chairs are original, with wire racks under each seat for a spectator to place his hat or her parasol.

In the winter of 1892 this room was packed with townspeople—equal parts disdainful of and fascinated by the divorce seekers—reporters, and other divorce colonists. Maggie De Stuers took the stand to plead for freedom from her husband, a titled Dutch diplomat whom she claimed had tried to institutionalize her and take control of her fortune. Maggie was a niece of the wealthy and powerful Astor family, and the attention her presence brought to the city sparked a nearly two-decade effort to restrict access to divorce.

That campaign was led by Episcopal bishop William Hobart Hare. His home church still stands in Sioux Falls, about a mile south of the courthouse. Another quartzite building, it was constructed in 1889 thanks to a sizable donation from Maggie De Stuers’s uncle, John Jacob Astor III. He built the church in memory of his late wife Charlotte Augusta, who had supported the bishop’s missionary work; her name is still engraved on its walls, and during the era of the divorce colony, it was known as St. Augusta Cathedral.

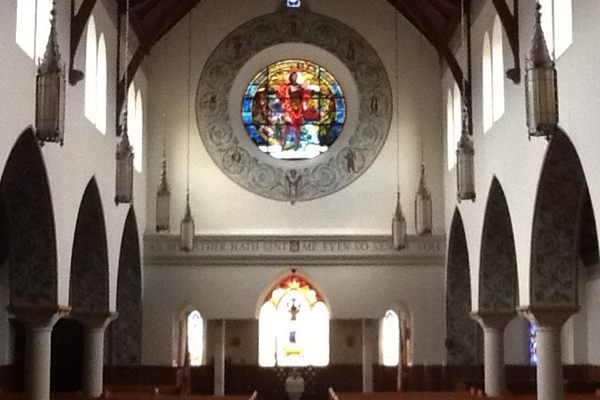

Today it is called Calvary Cathedral, and though the space has grown and modernized with the congregation over the last 130 years, much of the original building remains. “It’s the hub from which we do everything else,” says cathedral dean Father Ward Simpson. “All of the ministry revolves around that hub, all of that history, all of the people who worshiped there.” Parishioners can walk through the same massive wooden doors Maggie did during her stay in Sioux Falls (though they have been relocated) and from the pews, they can see a surprising artifact of the divorce colony above the altar: three stained glass windows depicting the crucifixion, resurrection, and benediction. The memorial panes at the bottom of two of them, however, have been laboriously scratched out.

These colorful windows are evidence of the personal feud that fueled the fight over divorce in Sioux Falls. Hare had long been outspoken against what he saw as the evils of divorce, but because of his close connection to the Astor family, he was particularly incensed by Maggie’s divorce—and her rapid remarriage. Maggie was a devoted member of the parish during her time in Sioux Falls, and she donated $1,000 (about $33,000 today) to the church for these works of art. “I won’t have them,” Hare insisted. “I’d as lief”—gladly—“paste up the flaming placards of a low circus.”

Though one window was hung in the 1890s with Hare’s blessing—its memorial pane replaced with one honoring Charles Smith Cook, a man of Sioux heritage who had been ordained by the Episcopal Church—the other two were hidden away for years. Eventually, they, too, were placed in the sanctuary, but with their dedications obliterated. But if you look closely enough below the image of Jesus blessing a child, you can just make out the outlines of a name: Mary Alida, the daughter Maggie lost at the age of eight.

“The controversy has faded completely,” Simpson says. He’s talking about both the fight over windows and over divorce. Since the era of the divorce colony, when the Episcopal Church was a leading advocate of limiting divorce access, “the church has come a long way on the issue,” he says. “Divorce is never a good thing, but we recognize there are times when it’s the lesser evil, and just because you divorce doesn’t make you an outsider.”

As for the windows, the congregation has decided that when it comes time to do repair work on the stained glass, the original names will be restored to the defaced memorial plates. “[Our predecessors] tried to eliminate these people from the history,” Simpson says, “and that shouldn’t be.”

The divorce colony was shuttered in 1908 when South Dakota’s citizens voted to extend the residency requirement to one year, making it as long as that of many other states. But it was not the victory that Hare had imagined it would be. Divorce rates nationally continued to rise, and so did public acceptance of the choice to leave a bad marriage. The divorce colonists who had briefly called Sioux Falls home had proven that women would seek autonomy over their lives, despite the legislative, judicial, religious, and social obstacles placed in front of them.

![Anne Bonny and Mary Read were both "convicted of piracy at a Court of Vice Admiralty [and] held at St. Jago de la Vega on the Island of Jamaica, 28th November 1720," according to the inscription accompanying this 1724 Benjamin Cole engraving from <em>A General History of the Pyrates</em>, by Daniel Defoe and Charles Johnson.](https://img.atlasobscura.com/5_kDHgENxQkc0QzZuPs_kICvmEP5JNCV8bcXDI7m5Do/rs:fill:600:400:1/g:ce/q:81/sm:1/scp:1/ar:1/aHR0cHM6Ly9hdGxh/cy1kZXYuczMuYW1h/em9uYXdzLmNvbS91/cGxvYWRzL2Fzc2V0/cy81NDQ0ZGNiMi1m/YzRkLTQ4YjUtYTVh/MC0xYzU2ZDliOTY0/YjY1NGNkMWI4MWEw/OTExMDM5ZTZfQW5u/ZSBCb25ueSBhbmQg/TWFyeSBSZWFkIC0g/RmVtYWxlIFBpcmF0/ZXMgaW4gMTgwMHMu/anBn.jpg)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook