What Were 29 Exotic Snakes Doing in a U.K. Trash Bin?

Wriggling in pillowcases, trying to stay warm after being illegally abandoned.

Desperate people have long used fire and police stations as safe places to leave infants they can’t care for. Unwanted animals more often are either dropped at animal-rescue facilities or, unfortunately, set free outdoors.

But last week, 29 snakes were left at a fire station in the northeast of England—in the trash.

In the wee hours of February 14, a passerby walking behind the Farringdon Community Fire Station, in a quiet suburb of Sunderland, noticed a pair of tied-off pillowcases (one of them with a colorful Toy Story theme), partly full, slumped against the fire station’s trash bin. And the sacks were moving.

Because they were full of snakes.

Thirteen royal pythons (aka ball pythons)—in a variety of colors, each about three feet long—were split between the two bags.

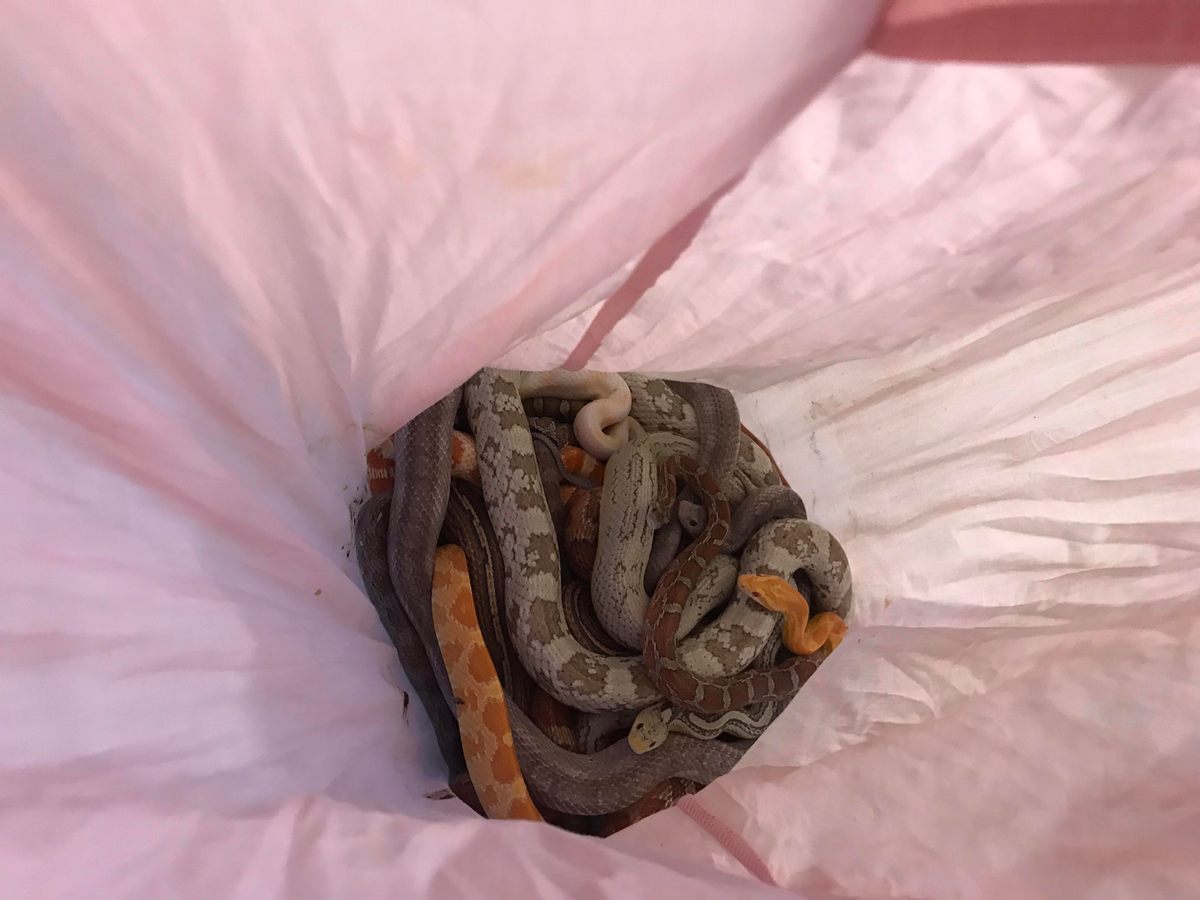

The next day, firehouse staff discovered two more wriggling pillowcases—pink ones—left inside the bin. One was stuffed with 15 corn snakes, the other with a male carpet python (the latter can reach nine feet in length, though this particular one was much smaller).

An inspector from the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) secured the snakes and took them for a veterinary check-up. Twenty-eight of them are now warm and safe, though the 29th has died. But if they hadn’t been found, all 29 snakes would have ended up dumped at the nearest landfill.

Meanwhile, the mystery of who bagged them up and abandoned them in the cold remains unsolved. And authorities are scratching their heads.

Despite firehouses’ reputation as safe havens, the location may have been incidental. “If someone had wanted the snakes to be found, we would expect them to have used the front steps of the station,” says Trevor Walker, an RSPCA inspector involved in the case. “Whoever did this discarded them without any concern for the animals, and they went around back to avoid being found out.”

None of the found snakes is venomous. And all are exotic: Royal pythons come from West and Central Africa, carpet pythons are from Australia and nearby islands, and corn snakes are North American. The rescued animals appear to have come from a collector or breeder.

Abandoning snakes in this way isn’t just cruel, says Evangeline Button, the RSPCA’s wildlife and exotics expert. It’s also against the law.

“It is illegal under the (amended) Wildlife and Countryside Act of 1981 to release, or to allow to escape, any species that are not native to the U.K.,” she says. If caught, an offender could face a 20,000-pound (about $26,000*) fine and up to six months in jail. “Non-native species could pose a serious threat to our native wildlife.”

Case in point: Consider the devastation in the Florida Everglades caused by escaped Burmese pythons—aggressive, sometimes 20-foot-long snakes that are eating their way through the native wildlife and outcompeting native species for food and other resources.

The United Kingdom has just four native snakes: two species of grass snake, the smooth snake, and a venomous adder. Already, invasive species—perhaps liberated pets—have introduced a deadly snake fungal disease that now threatens these native animals, which are already declining due to habitat loss and other factors.

Even if they’d managed to escape their sacks, “none of the snakes dropped off in those two incidents would be able to survive long in the U.K. winter,” says Terry Phillip, a herpetologist at Reptile Gardens in South Dakota. Native snakes only get through Britain’s coldest months—when temperatures can hover around 35 degrees Fahrenheit—by hibernating, and these exotic species are built for warmer conditions. Still, even if the invaders were short lived, “disease from captive animals can easily be spread to wild populations this way.”

Phillip notes that the pythons, while not rare, would be worth as much as 1,500 pounds (about $2,000) on the collectors’ market. Indeed, reptile ownership has grown significantly here in the past decade; conservatively, U.K. citizens today own more than two million pet snakes, with royal pythons and corn snakes two of the most popular species. (Some ownership estimates are much higher.)

The rescued animals, minus the one “emaciated” python that died, were deemed healthy by the veterinarian. Walker then volunteered to transport them “in the warm boot of my car—please don’t tell my wife”—100 miles to a reptile specialist in Yorkshire, where they’re now getting the care they need. “Hopefully, some of them can be re-homed,” he says.

He says that it’s unusual for the RSPCA to deal with such a high volume of reptiles. “We’ll occasionally pick up, say, a lizard walking up the high street of the village,” he says. “But that’s a one off—an animal that escaped its tank and walked out the door.”

“Then again,” he adds, “tomorrow we might find 29 bearded dragons abandoned.”

Since the snake rescue, there have been no more scaly surprises behind the Farringdon station, and the case is still under investigation.

“If we learn who committed the crime, we’d certainly want them disqualified from having animals in the future,” says Walker. And to anyone else wanting to rid themselves of a reptile collection? “Contact the RSPCA, or a reptile center or pet shop that has snakes,” he says. “Please don’t just dump them in the bin.”

* Correction: This story was updated to fix an incorrect currency conversion from pounds to dollars.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook