The Almost Perfect World War II Plot To Bomb Japan With Bats

Mexican Free-tailed bats spill out of Bracken Cave in Texas. (Photo: US Fish and Wildlife Service)

Mexican Free-tailed bats spill out of Bracken Cave in Texas. (Photo: US Fish and Wildlife Service)

Imagine: a quiet, tense night in the middle of wartime. A plane rips through the air above your city, rupturing the stillness. The bay doors open, and out whistles a bomb. It drops and drops. Everyone braces. But when it explodes, the city is filled not with the flash of impact, but with hundreds and hundreds of tiny, whirling bats.

This ridiculous vision—in which Japanese cities were destroyed by a giant bomb full of bats that were themselves carrying tinier bombs—was called Project X-Ray, and it was but a claw’s breadth from becoming a reality.

It took a dentist to come up with such a nightmarish plan. Like many Americans, Dr. Lytle S. Adams was incensed by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, enough to turn his mind towards the war effort. Adams had just returned to his Pennsylvania home from a vacation in New Mexico, where, he remembered years later, he had been “tremendously impressed” by the Mexican Free-Tailed Bats that migrate through the state and roost by the millions in Carlsbad Caverns.

Adams read up on bats. He returned to Carlsbad Caverns and captured some of his own (it was a different time). Through study and observation, he realized that the little critters are war machines, perfectly calibrated for withstanding high altitudes, flying long distances, and carrying heavy loads—for example, timed bombs.

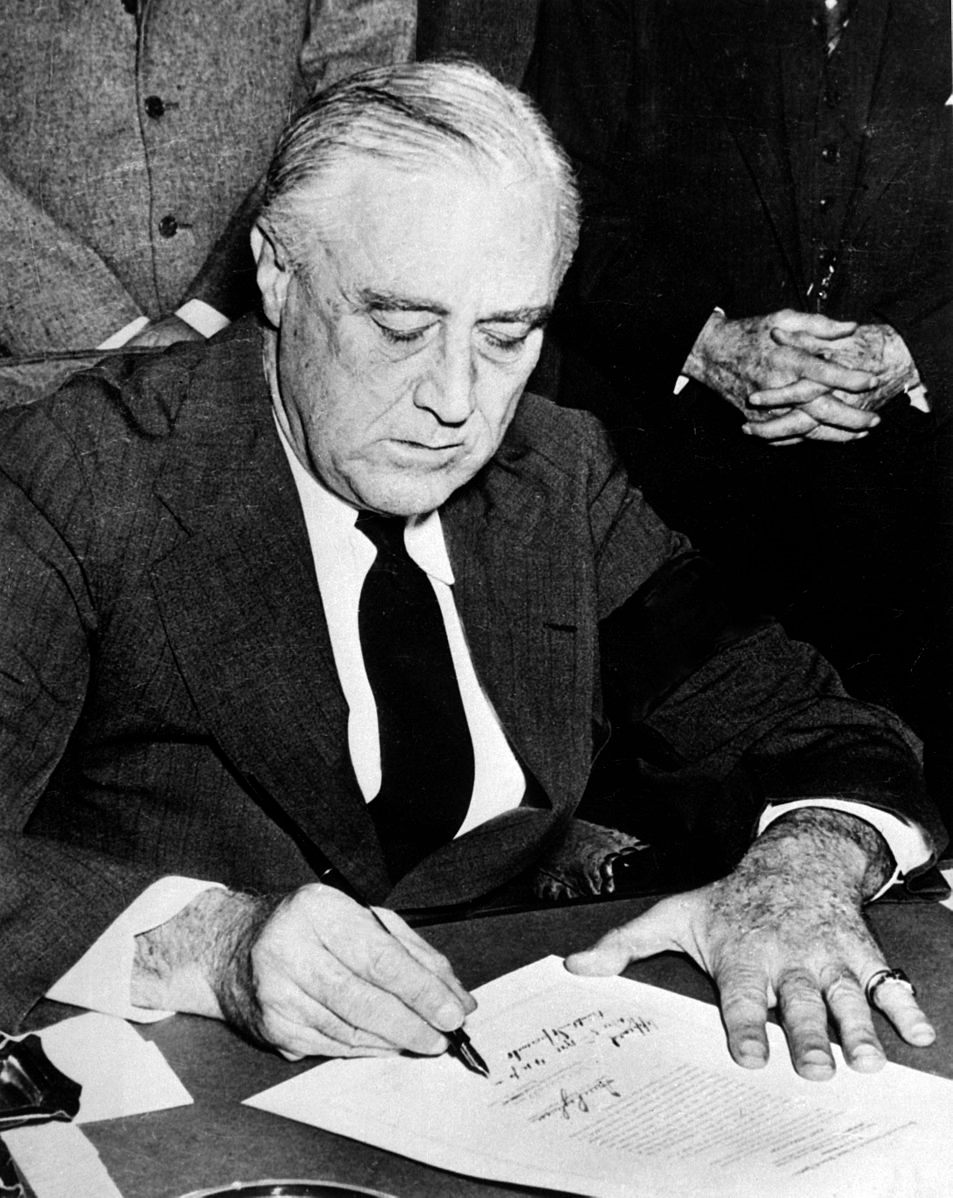

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signs a declaration of war against Japan on December 7th, 1941. (Photo: National Archives and Records Administration)

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signs a declaration of war against Japan on December 7th, 1941. (Photo: National Archives and Records Administration)

At the time, “Americans’ image of Japan was of crowded cities filled with paper-and-wood houses and factories,” C.V. Glines writes in Air Force Magazine—in other words, the kind of metropolis that could be wiped out with a struck match. Enough bats, Adams thought, could incinerate such a city just by doing what bats do best—spreading out and hiding in eaves and attics. Of course, first the bats would have to be outfitted with tiny bombs and delivered to Japan. But, provided he figured this part out, “what could be more devastating than such a firebomb attack?”

Adams was convinced. So on January 12th, 1942, barely a month after the Pearl Harbor attack, he drew up a proposal and sent it to the White House.

Adams’s letter had all the hallmarks of a crackpot scheme. It was bombastic: it promised a plan that would “frighten, demoralize, and excite the prejudices of the Japanese Empire,” and ventured that “the millions of bats that have for ages inhabited our belfries, tunnels and caverns were placed there by God to await this hour.” It was paranoid, and warned that the plan “might easily be used against us if the secret is not carefully guarded.” Most of all, it was confident: “As fantastic as you may regard the idea,” Adams wrote, “I am convinced it will work.”

The Mexican free-tailed bat, pictured on the right, is smaller and more common than other species such as the Western Mastiff, on the left. (Photo: Daniel Neal/Flickr)

The Mexican free-tailed bat, pictured on the right, is smaller and more common than other species such as the Western Mastiff, on the left. (Photo: Daniel Neal/Flickr)

Whether because of Adams’s rhetorical skills (or, more likely, because of his friendship with First Lady Eleanor), the proposal made it to President Roosevelt’s desk. Roosevelt sent Adams to see Colonel William J. Donovan, the head of wartime intelligence, along with a letter of his own. “This man is not a nut,” it read. “It sounds like a perfectly wild idea but is worth looking into.”

So Adams set about looking into it. He built up a coterie of supportive scientists, including Donald R. Griffin, the discoverer of echolocation, who called the plan “bizarre and visionary” and said that, if done correctly, it was “likely to cause severe damage to property and morale.” Adams took a team of University of California field naturalists on a bat-collecting trip (“we visited a thousand caves and three thousand mines,” he later recalled), and, after more testing and observation, settled on a species—the Mexican Free-Tailed bat, the very type that had originally inspired the plan. Free-tails are strong, hardy, and, most importantly, plentiful. Adams and his crew netted hundreds of them outside of one Texas cave, and sent them back to Washington in refrigerated trucks.

Two major tasks remained: designing the mini-bombs that each bat would carry, and the larger bomb that would house the whole shebang. The first problem was given to Dr. Louis Fieser, best known as the inventor of military napalm. It was a tricky project—the bombs had to be light enough for the bats to carry, and they couldn’t contain reagents, like phosphorus, that reacted with oxygen, because their bat carriers had to be able to breathe. Fieser settled on a light pill-shaped case made out of nitrocellulose, or guncotton, and filled with kerosene. A capsule on the side of the bomb held a firing pin, which was separated from the cartridge by a thin steel wire. The whole thing weighed seventeen grams (or about as much as three American quarters), and dangled from a string.

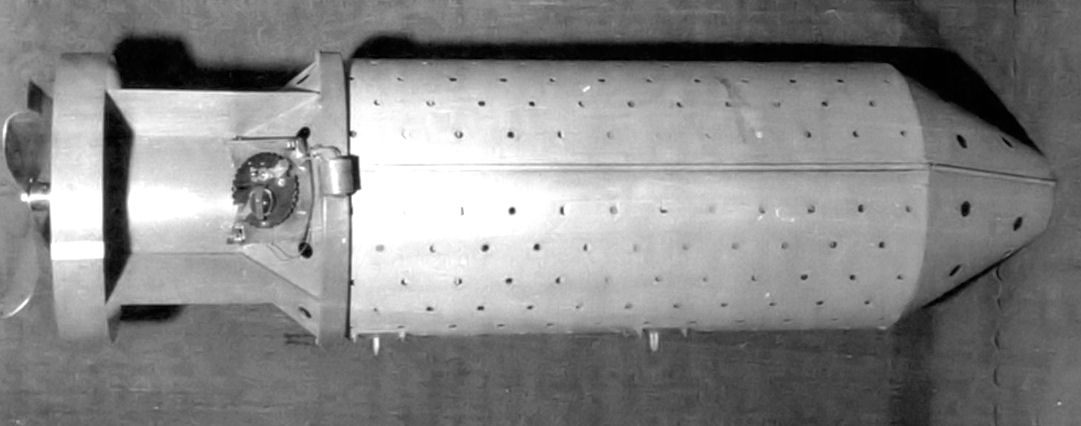

The bomb canister, built to hold over a thousand bats. (Photo: United States Army Air Forces)

The bomb canister, built to hold over a thousand bats. (Photo: United States Army Air Forces)

The larger, housing bomb was entrusted to the Crosby Research Foundation, a joint venture of famous crooner Bing Crosby and his brothers Bob and Larry. Based on a design by Adams, it looked, from the outside, like a normal bomb, a cigar of sheet metal with a tapered nose and fins. But on the inside, it was outfitted with a parachute and heating and cooling controls, and stacked with enough cardboard trays to hold one thousand and forty bats.

The whole thing was meant to work like this: To start the clock ticking, technicians would inject a corrosive solution, copper chloride, into the side cartridge, and then clip the bomb to the bat’s chest. They would then load the bats into the trays and the trays into the bomb, cool it down enough that the bats would think it was hibernation time, fly the whole thing to Japan in the belly of a plane, and release the bomb over the target city. In midair, the bomb would set free the trays, which would stay attached to the parachute. The bats would thaw out, wake up, and disperse, settling into nooks and crannies all over the city.

Then, each bat would gnaw through its string and take flight again, leaving the structures riddled with mini-bombs. When the copper chloride within each bomb finally dissolved the steel wire, the firing pin would snap, igniting the capsule and, soon after, the whole building. In this way, the industrial cities of Japan would be burned to the ground, bat by bat.

The Carlsbad, New Mexico Army Air Base, post bat bomb test. (Photo: United States Army Air Forces)

The Carlsbad, New Mexico Army Air Base, post bat bomb test. (Photo: United States Army Air Forces)

The military renamed the idea “Project X-Ray,” and began tests. Some went well: a trial run at Utah’s Dugway Proving Grounds resulted in the partial destruction of the “Japanese Village,” a mockup settlement. “The regular bombs would give probably 167 to 400 fires per bomb load where X-Ray would give 3,625 to 4,748 fires,” concluded the Chief Chemist. Others were less successful: perhaps excited to be home, bats participating in a test at the Carlsbad Army Airfield escaped with their explosives and incinerated the whole test range before roosting calmly beneath a fuel tank.

More tests were scheduled, but they were pushed off. In 1944, Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King canceled Project X-Ray, not for ineffectiveness or sheer lunacy, but because all resources were being redirected to that great destroyer, the atomic bomb. For the remainder of his life, Dr. Adams dedicated his powers of invention and persistence to smaller ideas, including prairie seed bombs and a fried chicken vending machine. But he maintained the bat bomb’s legitimacy until his death. Unlike the atom bomb, he says, his method would have caused the devastation of Japan, “but with small loss of life.” We’ll never know.

A bat bomb recruit, holding a mini-bomb prototype. (Photo: United States Army Air Forces)

A bat bomb recruit, holding a mini-bomb prototype. (Photo: United States Army Air Forces)

Naturecultures is a weekly column that explores the changing relationships between humanity and wilder things. Have something you want covered (or uncovered)? Send tips to [email protected].

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook