The Ice-Skating Dandies of 18th-Century Paris

The frozen fields were home to tight pants and graceful, showy moves.

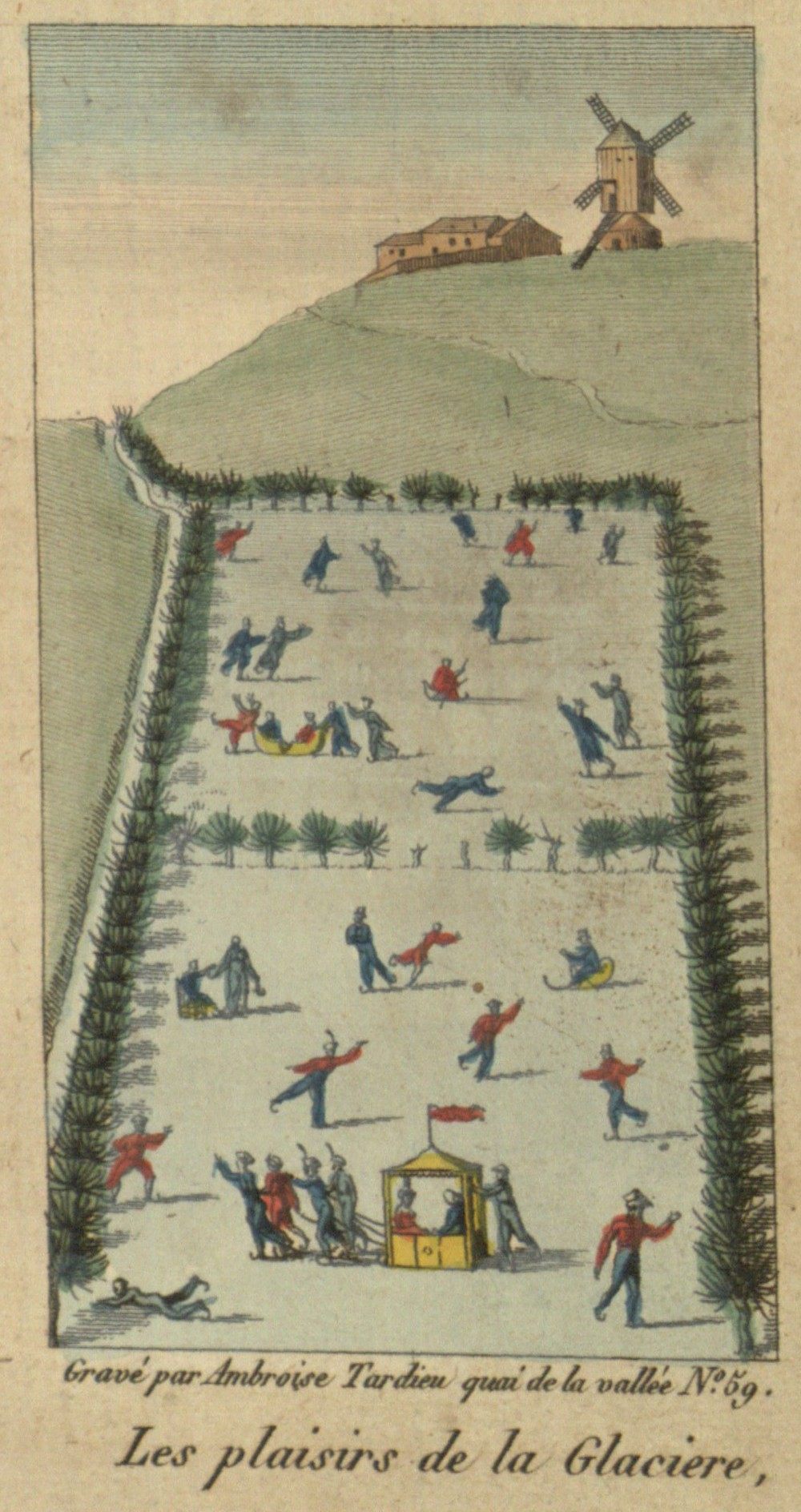

In the 18th century during the brisk winter months, Parisians flocked to the glistening frozen fields of La Glaciére, or the Glacier. The grassy terrain, flooded with water and frozen over, was an icy playground for upper-class citizens. And none were more showy than the male ice skaters dressed in bicep-revealing red jackets, tight pants, and graduation caps.

These fraternities of gentlemen showed off with challenging jumps and graceful arm movements—charms that could “seduce weak mortals,” according to the 19th-century French ice skater Jean Garcin. “There are no good skaters anywhere but in Paris,” he boasted.

Ice skating is a centuries-old pastime. Before bladed skates were invented around the 14th century, people tied bones to their feet and pushed themselves along the ice with poles. It was primarily used as a mode of transportation, but became a popular leisure activity reserved for aristocratic men in France during the late-18th-century reign of Louis XVI. They formed skating clubs or fraternities to practice together, shovel snow off the ice, and protect rinks from hooligans. Women wouldn’t be allowed into clubs until 1833, writes James Hines in Figure Skating in the Formative Years.

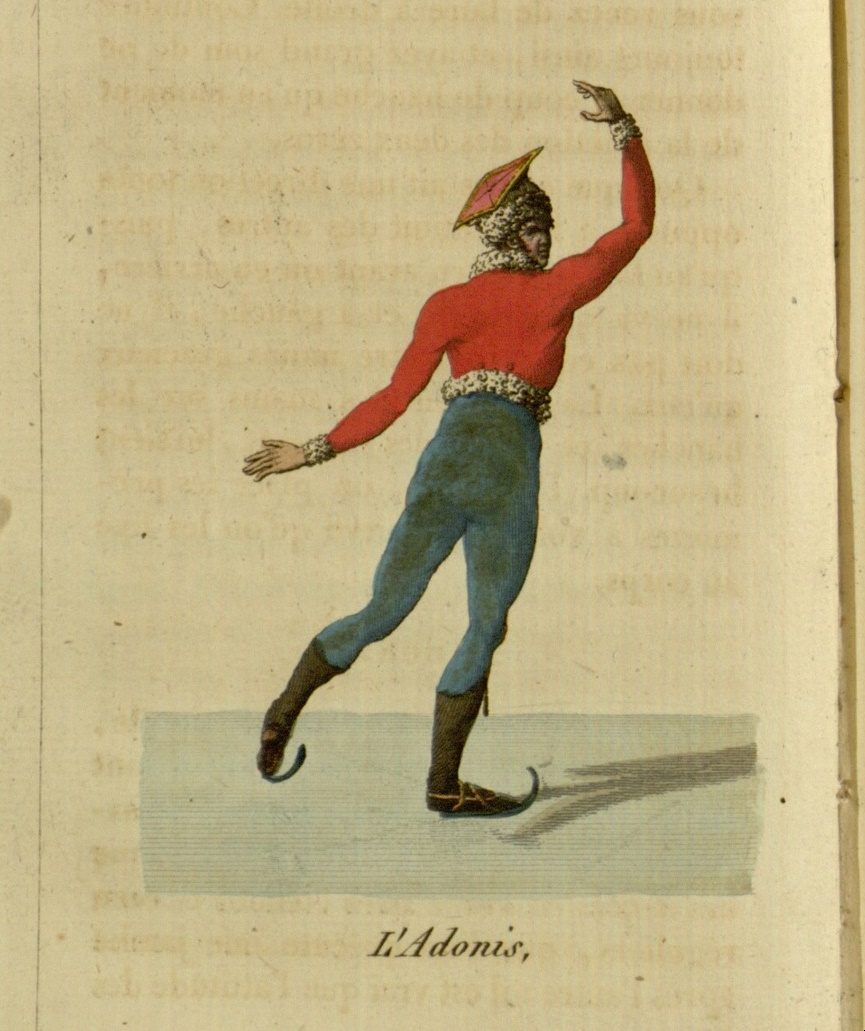

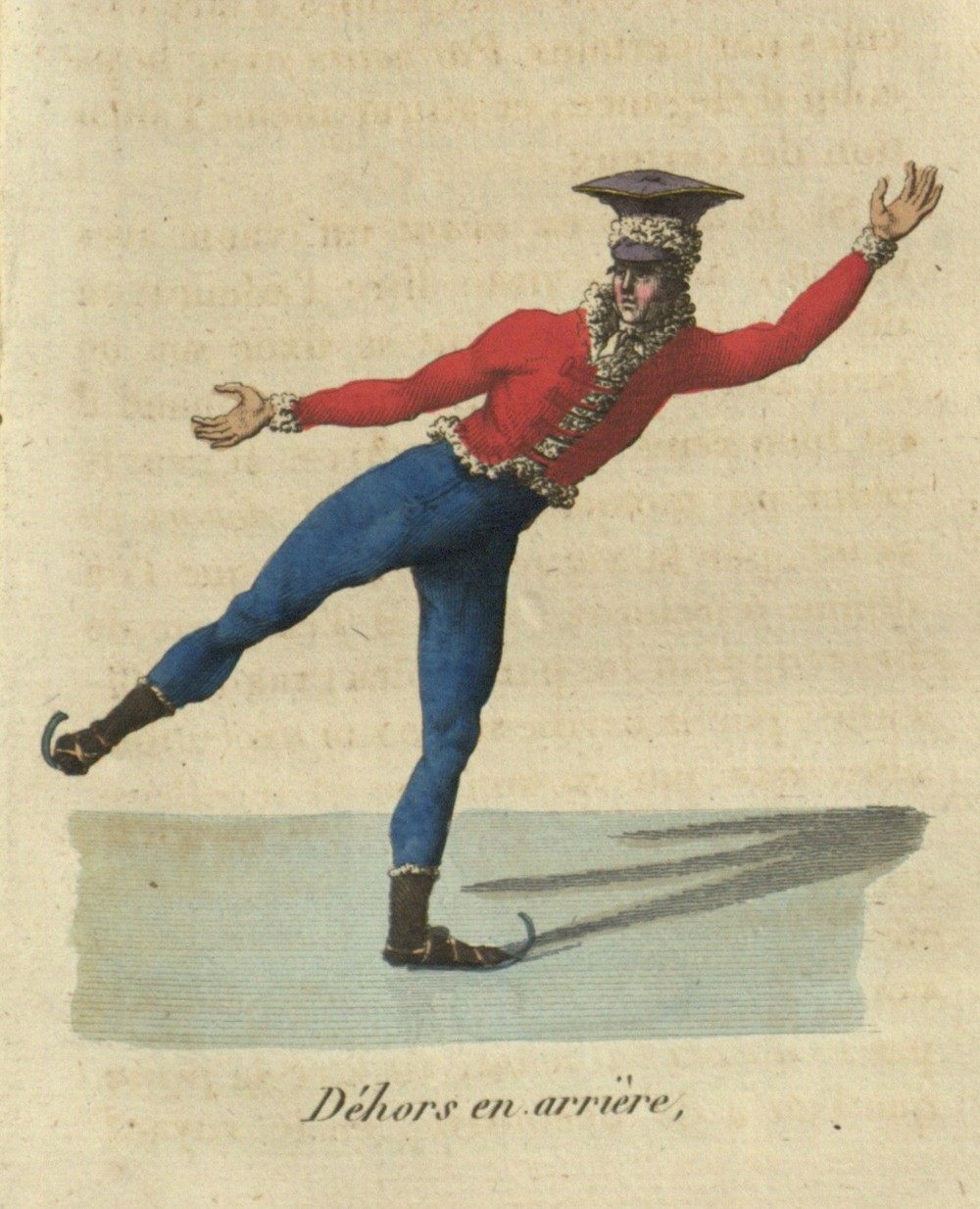

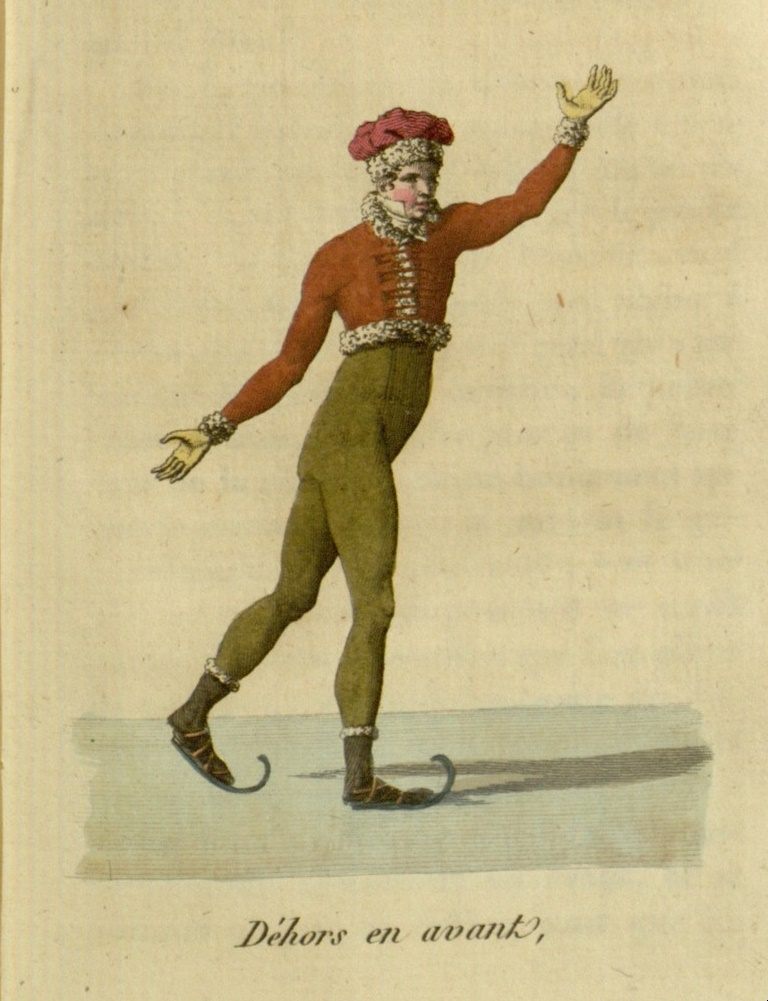

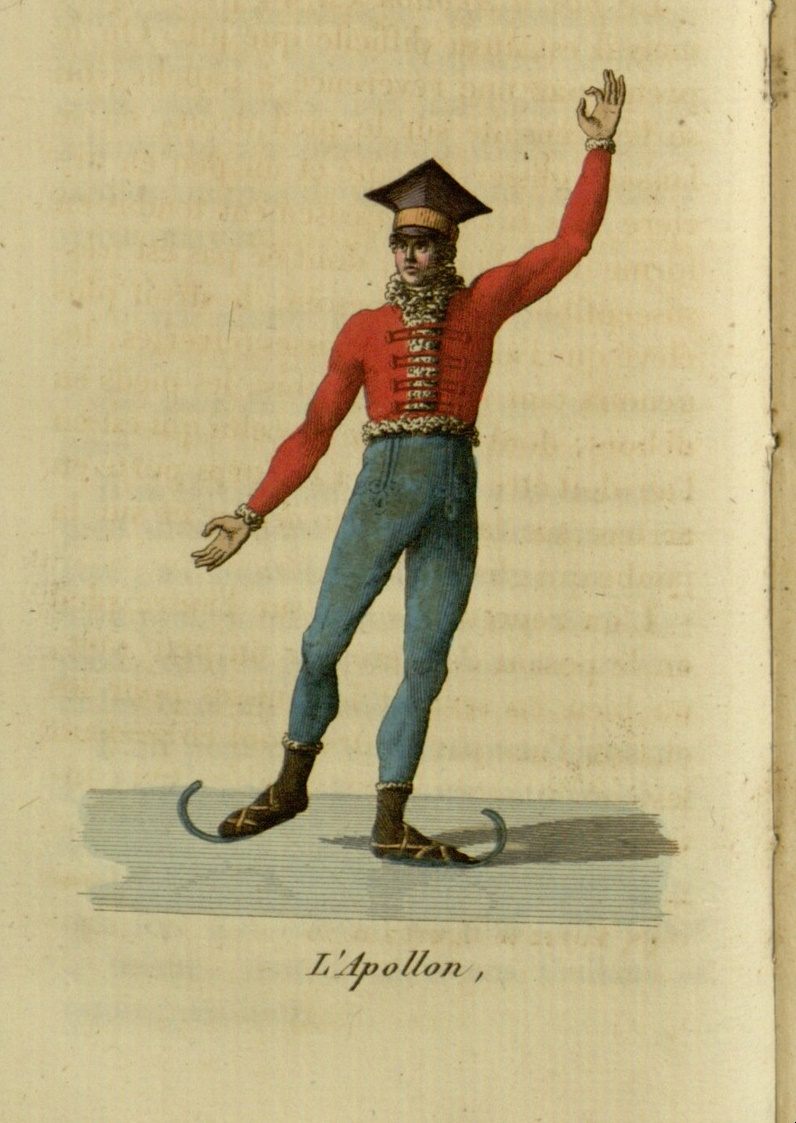

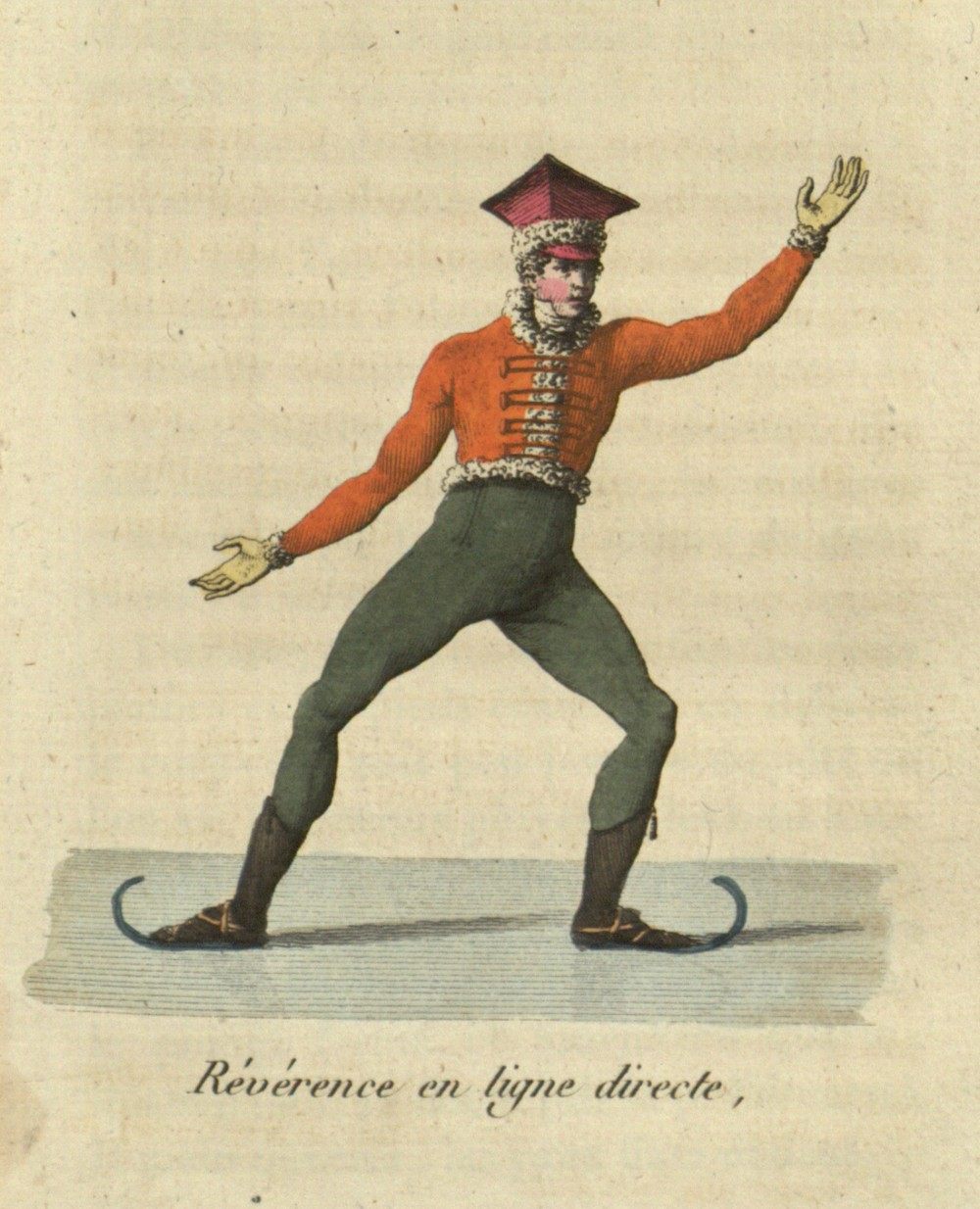

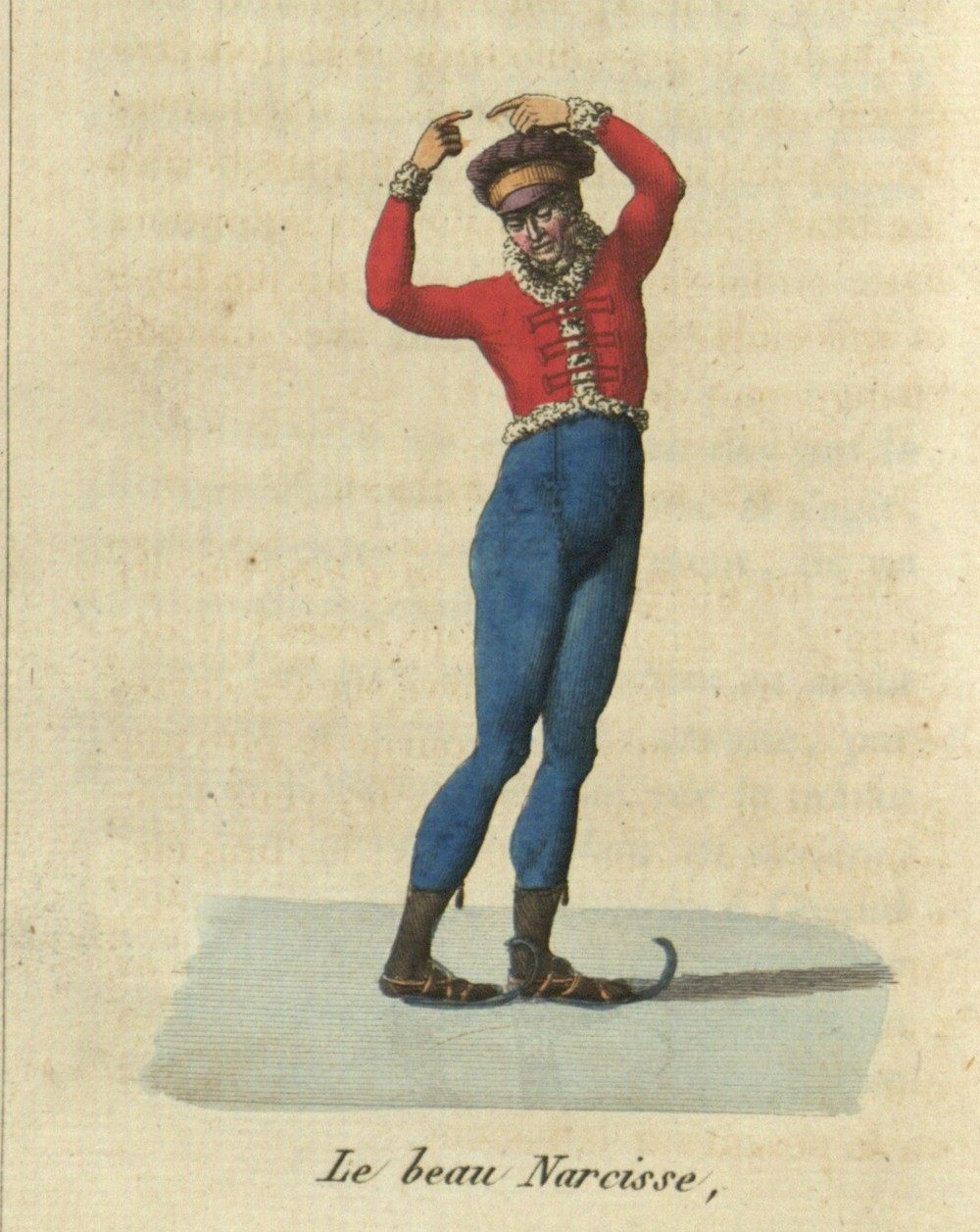

During the early 1800s, Jean Garcin was a member of the skating fraternity Gilets Rouge, or red waistcoats, an elite all-male group of skaters whose philosophy valued artistic expression over athleticism. In the 1813 book Le vrai patineur, or The True Skater, or Principles of the Art of Skating with Grace, Garcin illustrates the typical uniform of a Gilets Rouge ice skater: a form-fitting embroidered vest or coat, tight pants, and academic caps with a square top and tassel, known as mortarboards, or berets. While it’s unknown what kind of audience Garcin wrote the book for, Hines suggests he may have written it specifically for the Gilets Rouge.

In his book, Garcin argued that the French style of ice skating reigned supreme. Part instructional manual and part treatise, Le vrai patineur was the second book published on ice skating and the first in French. Garcin captured the different kinds of moves often observed on the icy fields of La Glaciére, describing more than 30 figures—each with whimsical names. The book contains color and black-and-white illustrations of various poses, arm positions, and even suggested facial expressions.

“There was a kind of detail to the hand and the fingers, and you see that in these pictures,” says Mary Louise Adams, a sports sociologist at Queen’s University in Ontario. “This was a textbook and it was a treatise to show how French skating was better than these other kinds of skating in other countries where grace was not as important.”

As ice skating spread, countries embraced different techniques and styles. The French blended masculinity and beauty that wasn’t often seen on the rinks in England, Austria, and other countries of Europe. While Garcin thought foreign skaters lacked flare, he believed they could pick up this style, writes Adams in her book Artistic Impressions: Figure Skating, Masculinity and the Limits of Sport, quoting Garcin:

“The Germans, English, Danes and people from other cold places are incapable of skating otherwise, but look at them the first time they show their knowledge here: The body is bent, the arms swinging, the derriere pitches, or straight as a picket, all stiff, inflexible, without grace, without attitude. It is surprising to us, but after a few winters here with our skaters they change … though they are always missing a little softness of their movements and abandon.”

The French also called ice skating “patinage artistique,” or artistic skating, explains Hines. “The French skaters placed their emphasis on artistry, specifically artistry associated with dance,” Hines writes. “Garcin viewed technique as important, but artistic expression as preeminent.”

Garcin dedicated Le vrai patineur to Geniéve Gosselin, the premier dancer at the Academy of Music in Paris, and often employed language used to describe ballet. The elegance in the poise of the body was of utmost importance.

“As to the position of the body,” he wrote. “It should be developed graciously: the head held high, the eyes attentive to the direction of movement, the arms free but comfortably positioned, allowing free movement of the shoulders with each turn of the head.”

He instructed skaters to pay special attention to the positioning of the arms and hands, writing that delicate placement “contributes to the aplomb and grace of a skater.” If not holding a cane, the palms were both held open, “as if you are representing them to a friend,” and to raise the arms as when “one implores favors from heaven.”

The face was just as important as the fingers—the meaning of a move could be completely altered with a new facial expression.

“What is interesting is that the kind of image he was advising to conduct was built on very fine details, so historically that’s very different,” says Adams. “Think about North American physical culture right now. Men are not supposed to pay attention to little details about their bodies.”

Many of the moves were not only challenging and beautiful, but dangerous. Garcin devoted the last chapters to the risks and hazards of ice skating. He described the safest conditions to go out on the ice and gave advice on how to get out of a pond if a skater broke through ice and became submerged waist-deep in frigid water.

Garcin noted the half-revolution three jump of the Saut du Zephyre (the Zephyr’s Leap), a dangerous but spectacular move, and the perilous Pas d’Apollon (the Step of Apollo). Several of the shapes and figures resemble similar moves you would see on the ice today. For example, the Révérence (bow) is a kind of spread-eagle figure, which is a common move, says Adams. “It requires very open hip joints. The person in this image isn’t doing it exactly the same, but it’s the same idea,” she says.

Garcin also documented figure-eight patterns in moves such as Le Courtisan (the courtier)—the pattern a crucial move for the figures seen 80 years later at international competitions, writes Hines.

While there are vestiges of the intricately drawn figures and diligent documentation of Le vrai patineur in today’s ice skating, it’s also evident how much the activity has evolved over the centuries. Garcin was proud of the 18th-century French way of skating, and suggested that elegance and grace strengthened the practice.

“Who knows how many people in France shared Garcin’s views or not,” says Adams. “It was important to construct the French skater as more naturally graceful than his counterparts in other countries, and that was a way of demonstrating superiority.”

Le vrai patineur was translated with the assistance of Mariana Zapata.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook