The Incredible Complications of Living Atop the U.S.-Canada Border

The tough, restricted lives of the dozen people whose homes lie in both Maine and Quebec.

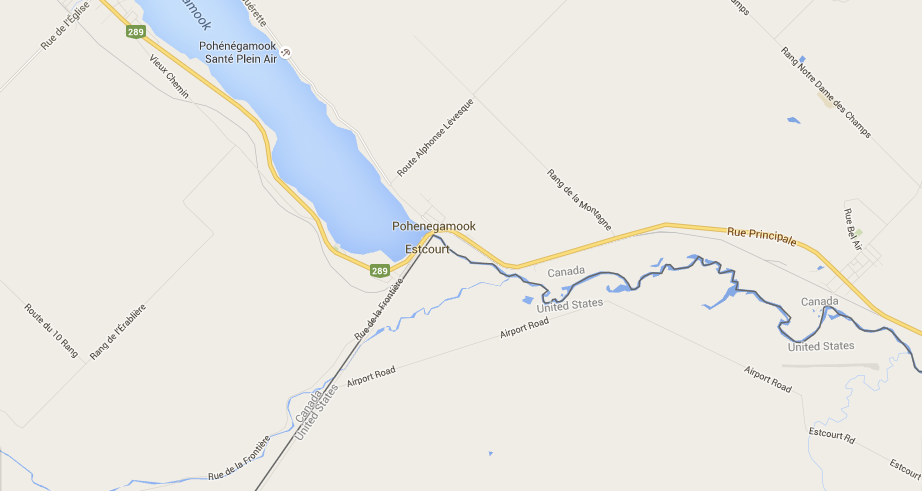

The quickest way to get to Estcourt Station from anywhere else in the U.S. is to exit Maine through the town of Fort Kent, loop through a corner of the Canadian province of New Brunswick, then drive on into Quebec, on an hour-long trek through gritty logging towns and French-speaking hamlets. You can cross back into Maine by way of the 2,970-person Quebec town of Pohénégamook.

Looming somewhere past a pizza place is the international border line, where Pohénégamook becomes Estcourt Station. But even after entering the American side through a checkpoint, it can be confusing to know which country you are actually in at any given moment. The border is a generally invisible boundary that indiscriminately hopscotches through gardens (a resident’s potato plants might be in Maine, while their radishes are in Quebec), runs through kitchens and across back porches.

The only foot bridge linking Maine and Canada where you can cross without checking in with customs (even though you are technically supposed to). (Photo: Kevin Williams)

Adding to the confusion in Estcourt Station is the fact that cottages on the U.S. side, along with the local Gulf Gas Station, all have 418 Quebec area codes and receive their electricity from Hydro-Québec. These American homes are among the only ones in the country to have Canadian area codes. There aren’t many of them, either: the last U.S. census lists the total population on the Maine side as four people. According to a representative of the U.S. Postal Service, mail is delivered to three addresses there twice a week.

When visiting Estcourt Station recently, I spied a bank of mailboxes with the familiar insignia of the U.S. Postal Service and drove toward it. But then a Canadian customs agent on foot seemed to materialize from nowhere, and approached my slow-moving car.

“Technically, you just entered the U.S. illegally,” she declared, with more of a shrug than any severity. “The border is behind the building.” To enter the U.S. in an above-board fashion, the friendly agent, Annica Lebel, advised that I check in with the U.S. customs agent about 100 yards down the road. It was difficult to believe there would be a staffed station of border agents at this nowhere post but sure enough, just down the street from the Canadian office was a gate to enter the United States.

A map showing Estcourt Station and Pohénégamook, and the US-Canada border. (Photo: © 2016 Google)

As the border angles northeastward it cuts through a couple of houses. In those homes, the border slices through living rooms and kitchens, a lasting legacy of a historical tug-of-war between the British and the United States over where the boundary should be. The Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842 set the current, somewhat bizarre border.

If you happen to be one of the dozen or so Canadians that live on Rue de la Frontiere, the border is both everywhere and nowhere. Although the delineation is less than clear in many areas, “Residents in the U.S. border area are responsible for knowing the location of the international boundary,” says Sean Smith, Public Affairs and Border Community Liaison Officer in the Boston field office of U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

A retired Canadian man named Raymond Trudel lives at 1165 Rue de la Frontiere, in a house that straddles both sides of the border. He’s allowed to enjoy all areas of his property, including his Canadian living room and his American backyard, but he can’t venture beyond the property line in back–if he did, he would be entering the United States illegally. He is however, allowed to wander around the U.S. in his own backyard, but nowhere else.

The boundary runs right through this vacant house. (Photo: Kevin Williams)

“Où est la frontière?” I ask Trudel. He motioned for me to come with him. We walked along his porch and he brought me to his back deck and pointed in a sweeping motion. The Canadian-U.S. border runs right across his back deck. If he’s going to grill, his burgers would be flame-broiled in the U.S.

He then points to his garden and shed. “Dans Etas-Unis.” It’s in the United States.

Lebel notes that someone like Trudel has to pay property taxes to the United States and Canada. “It’s definitely unique and causes all sorts of interesting situations,” she says. For instance, if his shed were vandalized, Trudel would have to call the Aroostook County Sheriff’s Office some two hours away, on the Maine side. A spokesperson for the Sheriff’s Department told me that hasn’t ever happened but that, yes, they would have to respond.

This is unlikely. Even though the U.S. census claims four people live in Estcourt Station, the year-round population is actually zero, according to Lebel. “The last full-timer was a retired forest service ranger, but he was old and moved to Fort Kent last year,” she says.

This gas station about 200 feet from the border was the site of the Michel Jalbert incident. (Photo: Mrgriscom/CC BY 3.0)

Apart from people like Trudel whose properties straddle the line, but are considered residents of Canada, there are a handful of Americans who spend summers in Estcourt Station. A couple from Kentucky owns one of the units. It’s not the easiest place to relax, though: “They are expected to abide by our hours,” says Lebel. “On the weekends they need to be in their houses by 5 p.m. and can’t leave until Monday morning at 9 a.m.” Those are the hours of the border crossing.

Even the Gulf Gas Station, located about 200 feet inside the U.S., heeds these hours; it’s open daily, but only from 9 a.m. to 4:45 p.m. This particular filling station was the site of the notorious 2002* incident in which a young Canadian father crossed the border after hours in an attempt to get gas and was nabbed by the U.S. border patrol. The man, Michel Jalbert, spent 35 days in jail for entering the U.S. illegally, something that Secretary of State Colin Powell later called an “unfortunate incident.”

Lebel said everything changed at the border after September 11, 2001. Even the customs agents don’t enjoy the cordiality that they used to. “They sort of do their thing and we do ours,” Lebel says. She patted the sidearm on her waist. “This can cause problems too.” She can’t just go over and chat with her U.S. counterpart, as she’d be entering a foreign country with a firearm.

Your laundry hangs in the U.S., while the rest of your life is in Canada. (Photo: Kevin Williams)

Despite the seemingly porous border here, the reality is that anyone wishing the U.S. harm would be making a very unwise decision if they tried to slip into the country via Estcourt Station. If they entered by vehicle they’d face hundreds of miles of unforgiving private logging roads that turn to pudding during spring and summer rains. And winter? Forget it unless you are driving a logging truck with chains and the ability to navigate 10-foot snowdrifts.

And if you tried to enter on foot through the Parc de La Frontiere, well, you’d have that same hundreds of rugged miles to contend with, except you’d be on foot.

Lebel said there are occasional rumors that this remote checkpoint will be closed, but for now, it remains open. Still, if you want to visit the most isolated border town in the contiguous 48 states, you better make sure you have a full tank of gas first. It’s a long drive.

*Correction: We originally referred to the border incident occurring in 2003. It took place in October 2002.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook