The Iowa Farmer Who Spent His Life Carving 81 Child-Sized Wooden Dolls

Some of the Dollies. (All photos: Lyz Lenz)

On the top floor of the Plymouth County Historical Museum in Le Mars, Iowa are 81 wooden dolls. Some dolls are black. Others are Chinese. There are two Syrian sisters made of walnut named the Blackwood sisters. The sisters have long ’70s style dresses and light honey-colored hair. Some of the dolls have short tight skirts, others have knee-length A-line dresses. There are tight bodices, shorts, platform shoes and heels. Yet, despite the diversity they all look the same—full figured bodies, bouffant hair, with large heavy lips and thick eyelashes that drop just a little, so that you can’t quite look them in the eye.

Each doll is 15 pounds and 39 inches tall and they are anatomically correct. Or they are correct up to their tiny hand-sewn skirts. Beyond that, Judy Bowman, the museum’s administrator tells me, “No no no no no no no. They are not.” And she leaves it at that.

Her discomfort with the question might be due to the museum’s personal relationship with the dolls’ mysterious maker—Robert Smith, a farmer from Battle Creek, Iowa. Smith was born in 1916. He died in 2002. No one knows much about Smith and there are few who remember him. Both his wife, Bethany, and daughter, Isabella died in 2012. Smith left no heirs and no immediate family besides the 81 wooden women he liked to call his “Firewood Floozies.” But they are most often known as the Dollies.

Judy Bowman, who was a friend of Isabella’s, told me that Smith mostly kept to himself. “He was quiet and known around town as eccentric.”

But Bowman couldn’t recall a particular story of his eccentricities, beyond the 81 obvious reasons.

Smith ran a large farm growing corn, but he always considered himself a type of artist. He and his wife Bethany collected antiques and Smith loved woodworking. They set up a barn as a museum on their property in Battle Creek. They called in the Barn Museum and it’s where in 1977, Smith began first displaying his Dollies.

Smith began carving the dolls in the fall of 1976. He carved his Dollies in the winter when the frigid and fallow fields kept him inside. He would stop in the spring and then start again in the fall after the harvest.

Smith began each doll with a sketch. He used wood from his farm and made every part of the dolls by hand except the hair, which he ordered from a catalog. Smith used a buzz saw to hack down the wood into large blocks and then trace them with his cardboard templates. Each spine is a spring meant for a screen door.

In 1977, the Ida County Pioneer Record described Smith’s process, noting that the artist “must be cruel to his doll long enough to insert the spinal column.”

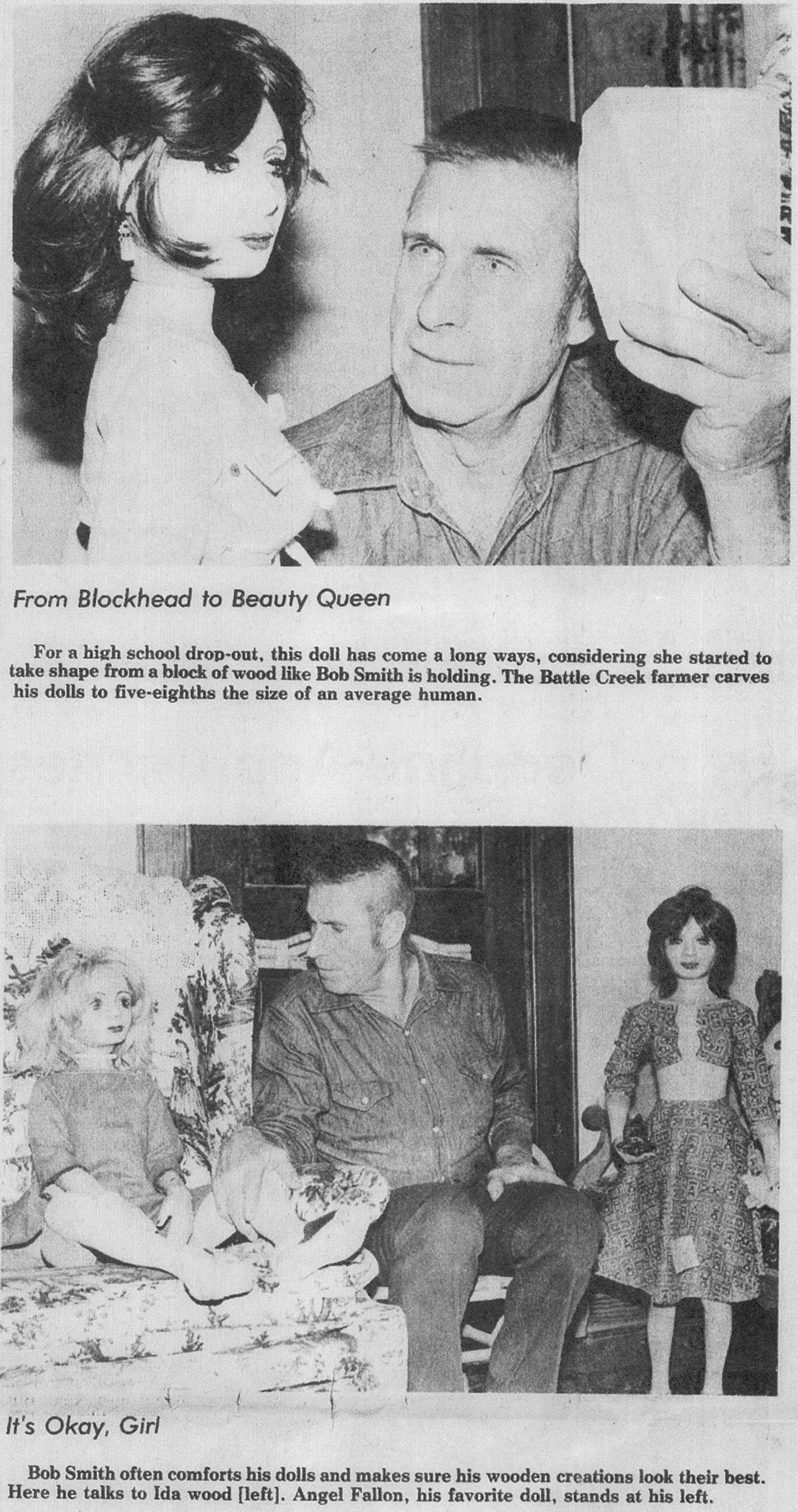

Photos from a May 19, 1977 story on Bob and his dolls in the Ida County Pioneer Record. (Copy of the article supplied by the Plymouth County Historical Museum.)

“The rest is painless, Smith assures. Every one of the legs has a screw eye and the legs and arms bend in the same place where Smith’s own body bends. The doll feet have five toes just like Smith’s own feet, which he uses as patterns,” the paper continued.

Smith sewed each outfit, picking the patterns for the clothing, and using the hand crank on the machine to get each stitch just right. He gave each doll shoes, accessories, a name and a story. Many of the names are puns and the stories are wooden jokes. Take Angel Fallon, one of Smith’s favorite dolls. He even pierced her ears. The story that accompanies her reads, “Hello! My name is Angel. Since I moved to my own apartment here I’ve been having this problem with rats in my kitchen. It could be worse because they all eat out. At first they were eating my cooking, too, but by now the survivors know better…My stomach is made of wood so I can eat anything.”

There is a doll with a blue mini skirt and knee high boots. She holds a cigarette. Smith told the Ida County Pioneer Record, “She’s 33 years old but she dropped out of the tenth grade last year.” She too is allowed a voice. “I hate housework. Mama says I must learn all the house-keeping arts to be happy and successful in life. When I tell her I don’t need that because I’m going to be a model or actress she says, ‘Little girl your head must be made of wood to think that way.’”

Smith said that their personalities just manifested on their own out of the wood in his hands. “I think it’s fun to make each doll a figment of the imagination, to be like a plastic surgeon,” Smith told the newspaper in 1977, which was the only known interview he ever gave about the dolls.

The newspaper reports that Smith was always fussing with his Dollies them. He would slip away to rearrange their skirts and reposition their accessories. “Women don’t know when they look their best,” he is quoted as saying. Bowman recalls that when the dolls lived in the Barn Museum one of the Smiths always stayed home with them. “There was someone always at home, watching over the dolls,” she told me.

Smith’s daughter Isabella was also an artist. Bowman recalls that Isabella raised geese and wrote about them in the same way that Flannery O’Connor wrote about peacocks. Isabella dropped out of Briar Cliff University in Sioux City, to come back home and help on the farm. She once described her father’s dolls as “Iowa folk art,” and she intended to display them at the Barn Museum until her death from cancer in 2012.

Bethany, Smith’s wife, was a little more tepid toward the dolls. She told the Ida County Pioneer Record, “You can’t view these dolls without a sense of humor. It took me a while to develop that sense of humor.”

And in 1977, when the dolls were first displayed, it seems the town of Battle Creek had a similar reaction. “No one liked them much,” Bowman told me. “Some people just have a hard time with art,” she explained. It wasn’t until the museum acquired them that they ever really found and audience and even then, the Dollies receive a mixed reaction.

“People leave notes in the guestbook saying they are weird or disturbing, but some people think the Renaissance paintings are inappropriate too.”

Bowman claims that Smith was inspired in part by Italian art, modeling his Dollies off of the Italian Lenci dolls.

Bowman told me that according to Isabella, a representative from the Smithsonian looked at the dollies and estimated each to be valued at $1,500. She also told me that the author Curtis Harnack, who grew up in Plymouth County, was a fan of the dollies and tried to persuade Smith to let him take them to New York. But Smith never relented.

The last doll was carved on May 5, 1998. After that, Bowman believes Smith was put in a nursing home. The dolls no longer live in the family’s barn, instead residing on the top floor of the Plymouth County Historical Museum. If you listen closely, you’ll notice that the museum plays “Hello Dolly” for them on loop.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook