The Photos that Exposed American Child Labor

From 1908 to 1924, Lewis Hine collected visual evidence of the nation’s youngest workers.

Ten-year-old Lalar Blanton, a textile worker, looks out the window of a North Carolina cotton mill in 1908. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-nclc-01345)

This year marks a century since the introduction of the United States’ first federal anti-child labor law.

The Keating-Owen Child Labor Act aimed to tackle individual states’ child exploitation by prohibiting the interstate sale of goods produced by facilities employing children. It targeted factories that employed children younger than 14, mines that employed children under 16, and any facility where children under 14 worked before 6 a.m., after 7 p.m., or more than eight hours per day.

Approved by Congress in September 1916, the Act and its child-protection provisions lasted all of two years before the Supreme Court struck it down as an unconstitutional imposition of federal might on state labor laws.

But though it was short-lived, the Act was just one part of a greater movement against child labor—one that had been gathering momentum for decades. In 1904, the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC) formed with the aims of ending child employment and providing young people with educational opportunities. At the time, according to U.S. census data, approximately 1.75 million children aged between 10 and 14 were gainfully employed.

As part of its campaign to raise awareness of child labor conditions, the NCLC hired photographer Lewis Hine to document the working lives of children around the country. From 1908 to 1924, Hine traveled around the nation, meeting seven-year-old oyster shuckers, 10-year-old cotton mill spinners, and six-year-old newspaper boys. His photographs, and the evocative captions gleaned from surreptitious interviews with the children, offer a stunning look at the breadth of child labor happening in the United States at the time. Below are some of Hine’s photos from the Library of Congress’ National Child Labor Committee collection.

(Photo: Library of Congress/National Child Labor Committee Collection/LC-DIG-nclc-00828)

Manuel, a five-year-old shrimp picker in Biloxi, Mississippi, was photographed in 1911 during his second year of employment at the Dunbar, Lopez, Dukate Company. Hine’s caption noted that the child understood “not a word of English. The pile behind him is a “mountain of child-labor oyster shells.”

(Photo: Library of Congress/National Child Labor Committee Collection/LC-DIG-nclc-01015)

Rosie, a seven-year-old oyster shucker at the Varn & Platt Canning Co. in South Carolina, was in her second year of employment when photographed in 1913. Hine’s caption reads: “Illiterate. Works all day.”

(Photo: Library of Congress/National Child Labor Committee Collection/LC-DIG-nclc-01059)

This boy worked as a driver for a coal mine in Brown, West Virginia. When he met Hine in 1908 he had been in the job for a year, working from 7 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. daily.

(Photo: Library of Congress/National Child Labor Committee Collection/LC-DIG-nclc-01824)

Hine described this young mill worker, Addie Card, as an “anemic little spinner.” She was photographed in 1910 at the North Pownal Cotton Mill in Vermont.

(Photo: Library of Congress/National Child Labor Committee Collection/LC-DIG-nclc-03869)

An eight-year-old “newsie” was photographed barefoot in a Waco, Texas street in 1913. Hine noted that some young newspaper sellers woke up around 3 a.m. to be able to work before going to school.

(Photo: Library of Congress/National Child Labor Committee Collection/LC-DIG-nclc-01668)

John Dempsey, estimated to be 11 or 12, operated a spinning mule at Jackson Mill in Fiskeville, Rhode Island. Hine’s caption stated that he “found no others below 14 in this mill” when he visited in 1909.

(Photo: Library of Congress/National Child Labor Committee Collection/LC-DIG-nclc-02892)

Ten-year-old Madeline Causey worked at Merrimack Mills, a textile manufacturer in Huntsville, Alabama. Hine met her in 1913, when she had been employed there for four months. Her job was to fill batteries.

1910 (Photo: Library of Congress/National Child Labor Committee Collection/LC-DIG-nclc-03487)

Hine captured these St. Louis newspaper boys smoking at 11 a.m. on a Monday in 1910.

(Photo: Library of Congress/National Child Labor Committee Collection/LC-DIG-nclc-00967)

Hine documented workplace injuries—often inadvertently. At 6 a.m. on August 14, 1911, he spotted eight-year-old Phoebe Thomas, heading to her job at the Seacoast Canning Company in Eastport, Maine. He wrote that the girl carried a ”great butcher knife,” which she used to cut sardines.

Shortly afterwards, Hine saw the girl again. This time she was running home in great distress, her left arm covered in blood. Hine photographed her as she ran, and learned that, while cutting sardines at the factory, she had sliced her thumb so deeply that the end of it was almost cut off. Immediately after the accident, Phoebe was sent home alone, Hine noted, because her mother was too busy to collect her.

The above photo shows Phoebe a few days after the accident. Hine photographed her one more time—a week after her injury. He wrote that Phoebe “was back at the factory that day, using the same big knife.”

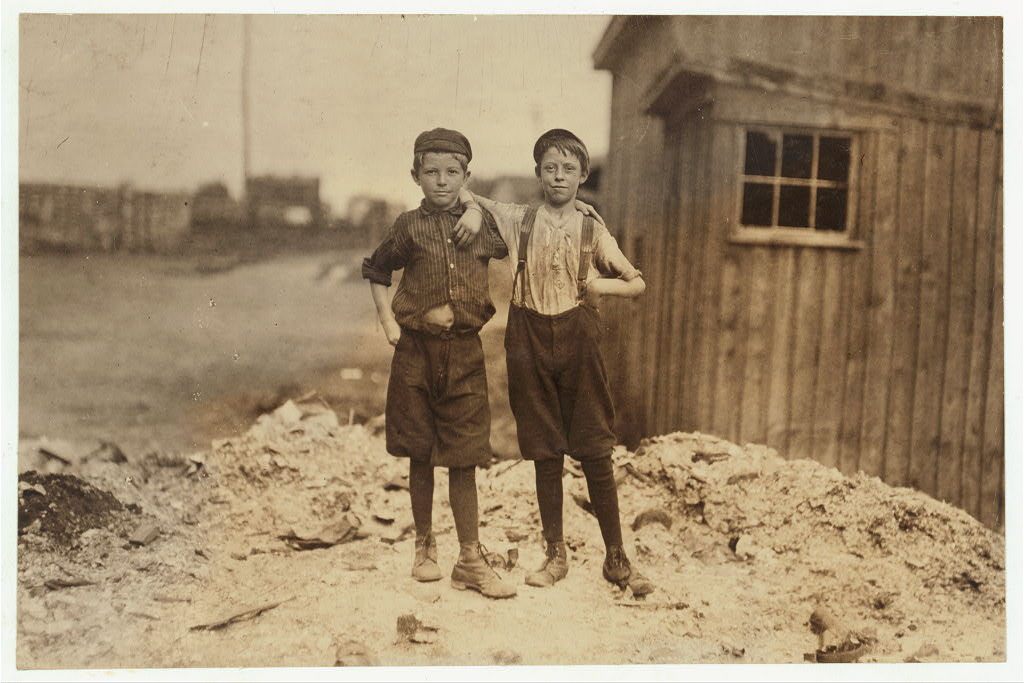

(Photo: Library of Congress/National Child Labor Committee Collection/LC-DIG-nclc-01296)

Frank Clark and Ashby Corbin, above, worked at a glass factory in Alexandria, Virginia. When he talked to the boys in 1911, Hine discovered that Frank “could neither read nor write, having been to school only a few weeks in his life.” Frank’s two older brothers also worked at the glass factory. His father was a candy maker.

Following the repeal of the Keating-Owens Act, federal child labor laws did not get reintroduced until 1933, when Franklin Delano Roosevelt debuted his New Deal. In the interim, however, Hine’s powerful photos helped the NCLC and other reform groups in their mission to get child-protective laws passed in individual states. According to census data, the number of gainful workers aged 10 to 14 in the U.S. fell from 1.4 million in 1920 to 667,000 in 1930.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook