Fossil Roads and a Sea Serpent That Wasn’t: Alabama’s Overlooked Prehistory

Oceans of Alabama (illustration by the author)

Oceans of Alabama (illustration by the author)

Say “Alabama” and the word “fossil” doesn’t immediately jump to mind. That’s understandable, the paleontological discoveries made in the Yellowhammer State rarely make the national news. Which is a shame, because Alabama has a rich prehistory that stretches from the Carboniferous shales of the Iron Hills to the Cenozoic clay near the gulf. A jumble of geologic eras are represented in the state, each carrying a wonderful array of fauna, including marine reptiles, weird arthropods, and ancient whales.

Here are four spots that embody the ancient world of Alabama.

The Beast from the Tombigbee

Greene County

The “Artemis” skeleton (courtesy Dana Ehret, Curator of Paleontology, University of Alabama Museums)

The “Artemis” skeleton (courtesy Dana Ehret, Curator of Paleontology, University of Alabama Museums)

The most complete Clidastes mosasaur in the world currently sits in a small case at the Alabama Museum of Natural History in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. The skeleton — nicknamed “Artemis” when she was discovered beneath the Hefflin Dam in 2002 — is intact down to the tiniest bones of the flipper, a find that is almost indescribably rare.

Resembling nothing so much as a komodo dragon with flippers, mosasaurs were marine predators closely related to modern lizards and snakes. Some species grew as large as 50 feet, though these leviathans are mostly known from incomplete remains. They were just one of the inhabitants of Alabama’s Cretaceous oceans — others included ginsu-toothed sharks, massive long-necked plesiosaurs, and tusked swordfish. But mosasaurs were the top predators of that long ago sea, devouring anything smaller than themselves, including smaller mosasaurs.

Artemis has never been formally studied, but the fossil menageries of the Alabama Chalk have. In 1946, the Chicago Field Museum spent a few months collecting in the warren of chalk gullies known as Harrell Station. They recovered a huge amount of material, including mosasaurs, sea turtles, and the scrappy remains of dinosaurs whose carcasses had floated out to sea. Currently, the Alabama Museum of Natural History owns Harrell Station, and much of their collection from the site is on-display.

Harrell Station (courtesy Dana Ehret, Curator of Paleontology, University of Alabama Museums)

Harrell Station (courtesy Dana Ehret, Curator of Paleontology, University of Alabama Museums)

The Sea Serpent That Wasn’t

Clarke County

Basilosaurus in the Alabama Museum of Natural History (courtesy Dana Ehret, Curator of Paleontology, University of Alabama Museums)

Basilosaurus in the Alabama Museum of Natural History (courtesy Dana Ehret, Curator of Paleontology, University of Alabama Museums)

In 1834, the discovery of the 40 million-year-old fossil serpent-whale Basilosaurus in southern Alabama set off one of the first great fossil rushes in United States history. Fossil prospectors and poachers flocked to Alabama, looking for spectacular finds. But one of them, Albert Koch, decided to cheat.

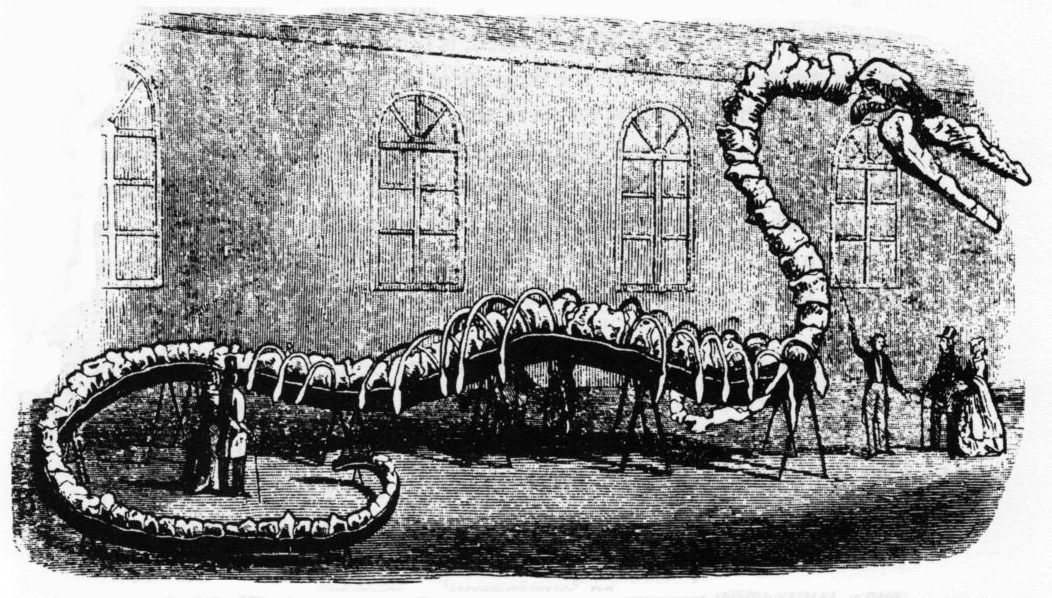

Koch, an enterprising con man with some background in science, went across the clay fields of Clarke County in 1845, looking for Basilosaurus remains. The vertebrae of the great whales were common enough in those days that farmers plowed them up in fields, set them to anchor fence posts, and used them for furniture. Koch bought remains here, discovered others there, and went to work. Soon, he was ready to unveil his masterpiece to crowds across America: Hydroarchos, the “water king,” a monster stretching 140 feet.

Hydroarchos, archival image

Hydroarchos, archival image

In fact, the Hydroarchos only stretched 119 feet, and to the trained eye was instantly identifiable as the cobbled together remains of several different serpent-whales. That didn’t stop Koch from successfully selling it for a tidy sum to King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia, who ordered it displayed in the Royal Anatomical Museum over the strenuous objections of its scientists. Koch whipped up another composite a few years later and sold it to a museum owner in Chicago, although this one was properly identified. It was destroyed in the great Chicago fire of 1871.

The real Basilosaurus is nowhere near as large as the fake Hydroarchos, reaching 65 feet. But it was equally formidable, with powerful jaws and long fangs — a worthy successor to the mosasaurs who had ruled Alabama’s oceans 30 million years before. Basilosaurus is now the state fossil of Alabama, and assorted remains (and an impressive complete skeleton) can be seen at the Alabama Museum of Natural History.

Basilosaurus (illustration by the author)

Basilosaurus (illustration by the author)

The Red Mountain Cut

Jefferson County

Red Mountain Road Cut (photograph by Greg Willis/Flickr)

Red Mountain Road Cut (photograph by Greg Willis/Flickr)

The city of Birmingham originally created the Red Mountain Road Cut to build an expressway linking downtown Birmingham to the neighborhoods south of the mountain. But what remained after construction ended was an exposed corridor of multicolored rock bands representing 190 million years of geologic history, more than any other road cut in the United States.

After some frantic lobbying by local paleontologists to stop the state from covering the walls of the Cut with concrete, studies began in earnest. The fossils of the Red Mountain Cut hail from the oceans of the Paleozoic, a vast era of life before mammals or dinosaurs. The earliest rocks represented were laid down 485 million years ago, in the Cambrian, at the dawn of multicellular life. Sponges, ancient corals, and strange sea lilies dot the rocks, the remains of ancient reefs. Also notable are the hard carapaces of trilobites, pillbug-like arthropods that scuttled across the ancient seafloor on rows of segmented legs — including remains of Birmingham’s own trilobite, Acaste birminghamensis.

The National Park Service named the Red Mountain Cut a National Landmark in 1987, and for a time it hosted a small paleontology museum and an open interpretive trail along the eastern cliff, complete with signs pointing out various geological and fossil phenomena. Unfortunately, the site has languished in recent years: the museum closed, the signs fell prey to weathering and graffiti, and the gates to the interpretive trail are often locked. The Alabama Paleontology Society is currently working to get the site restored. The defunct museum’s collections are on display at the McWane Science Center in downtown Birmingham.

Red Mountain Roadcut (photograph by Jim Lacefield)

Stephen C. Minkin Paleozoic Footprint Site

Walker County

Alabama Trackways (photograph by James Lacefield)

The most prolific source of Carboniferous trackways in the world sits in the hills of Alabama’s Walker County, beneath a cliff of crumbling shale. In 1999, a high school teacher poking around the spoil piles of the defunct Union Chapel Mine stumbled across something quite rare: the preserved footprint of an ancient amphibian. Amateur fossil hunters and professional paleontologists alike soon flocked to the site, hoping to collect everything they could before the mine was reclaimed and the fossils destroyed. Eventually, a deal was worked out with the state that preserves the site in perpetuity.

It’s a lucky thing, too, because the piles of black and grey shale that litter the ground beneath the cliff face are a rich source of trace fossils — things like footprints, burrows, body impressions, and other glimpses into past behavior. 315 million years ago, the site was a swampy beach, lapped by warm tides and overshadowed by horsetails as tall and thick as trees. A variety of amphibians skittered along the shoreline, leaving prints in the warm mud, hunting insects and each other. Fish schooled in the tidal flats, scratching gentle furrows in the silt. Worms burrowed, arthropods marched and jumped, and dead leaves fell and were buried. All of these traces were preserved in exquisite detail. Over 3,000 specimens have been removed from the site, among them delicate plant fossils and insect wings, huge and incredibly rare.

The Minkin site is officially closed to visitors, but it’s fairly easy to arrange a visit. The Alabama Paleontological Society leads monthly collecting trips, and they’re happy to have interested people along. While any scientifically valuable specimens found must be donated to a museum for further study, it’s possible to come away with plant fossils or the occasional footprint.

Union Chapel Mine (photograph by Prescott Atkinson)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook