Until 1950, U.S. Weathermen Were Forbidden From Talking About Tornados

I say tornaydo, you say tornahdo, let’s call the whole thing off, etc. (Photo: Daphne Zaras/WikiCommons Public Domain)

In the first half of the 20th century, tornados were all over the United States: destroying whole towns, screaming through the papers, tearing up the newsreels, and whipping Dorothy from Kansas to Oz.

But there was one place you couldn’t find them: the weather report. From 1887 up until 1950, American weather forecasters were forbidden from attempting to predict tornados. Mentioning them was, in the words of one historian, “career suicide.”

During that time, Roger Edwards of the National Weather Service’s Storm Prediction Center writes, “tornadoes were, for most, dark and mysterious menaces of unfathomable power, fast-striking monsters from the sky capable of sudden and unpredictable acts of death and devastation.”

Less than confident in their own predictive powers, and fearful of the responses of a panicky public, “the use of the word ‘tornado’ in forecasts was at times strongly discouraged and at other times forbidden” by the Weather Bureau, Edwards writes, replaced by euphemisms like “severe local storms.”

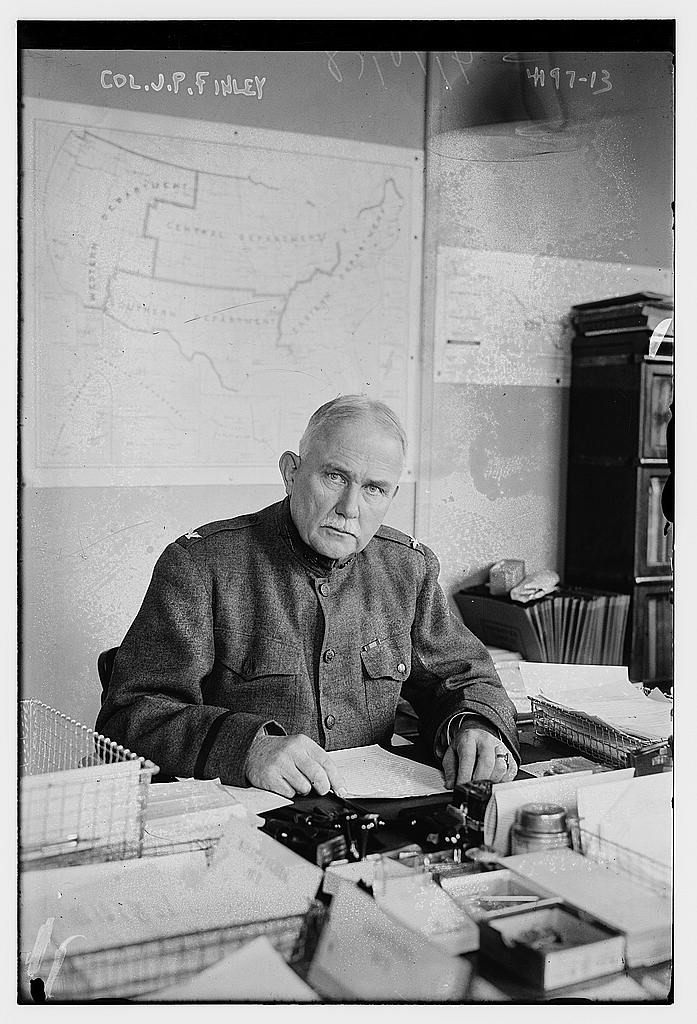

Colonel John Park Finley at his desk in 1917. (Photo: Bain/Library of Congress Public Domain)

Of course, a ban on the word “tornado” wouldn’t have been necessary without someone who really, really wanted to talk about tornadoes. That role was first played by John Park Finley, an officer with the Army Signal Office with a deep interest in severe storms. The U.S. Army Signal Service first opened a weather forecasting office in 1870, and when Finley enlisted in 1877, he joined it immediately, relates Nancy Mathis in Storm Warning: The Story of a Killer Tornado.

His hope was to develop a method of tornado prediction so that storms’ arrivals could be broadcast to local communities–possibly, he wrote, through the ringing of church bells “in some peculiar manner.” He visited storm sites and pored over historical twister accounts. Eventually, he began adding tornado forecasts to his in-house weather reports.

Some found his research promising. In 1885, the New York Times reported that, thanks to Finley, “trustworthy warnings” might soon provide a head start to “inhabitants of localities which may be threatened with disastrous visitations.” But others were not so enthused. In 1887, Mathis writes, “nervous superiors sent [Finley] new instructions: the word tornado was banned from forecasts.” Besides an excitable public, there were commercial concerns; the businessmen of Tornado Alley had “complained that Finley was giving potential investors the idea that their region was twister prone.”

When the department was reorganized, Finley’s new boss, General Adolphus Greely, doubled down on this conviction. “It is believed that the harm done by such predictions would eventually be greater than that which results from the tornado itself,” Greely wrote in a report to Congress. Other professionals agreed, saying that tornado prediction was a pipe dream. As meteorologist William Blasius put it in an 1887 meeting of the American Philosophical Society, “Just where the tornado will strike… no man can tell until within a few minutes of its passage.”

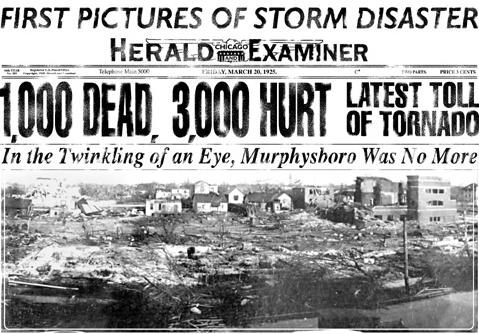

The Tri-State Tornado decimated towns across the Midwest and terrified citizens nationwide. (Photo: WikiCommons/Public Domain)

The Signal Office’s forecasting division was eventually transferred to the Department of Agriculture, where it became the U.S. Weather Bureau. Though the Bureau thrived in its new home, developing warning systems for everything from floods to hurricanes to forest fires, it held fast to its tornado position. “Forecasts of tornadoes are prohibited,” announced the Weather Bureau Stations Regulations of 1905, 1915, and 1934.

Meanwhile, Mathis writes, throughout the ‘20s and ‘30s, “the death toll from tornadoes mounted.” People facing a rash of storms–the Palm Sunday Tornado Outbreak; the Great Tri-State Tornado–were left on their own: “There were no warnings, no time for people to seek shelter.”

In 1938, the Weather Bureau eased up a bit, allowing its scientists to mention the storm-who-must-not-be-named in communications between emergency personnel. The public, though, was still left in the dark–until two Air Force meteorologists, Major Ernest J. Fawbush and Captain Robert E. Miller, were put on the case. After scrutinizing tornados in Alabama, Georgia, and Oklahoma, they developed their own prediction system. In 1948, after correctly predicting several outbreaks among themselves, they finally announced an upcoming doozy–the first tornado forecast in history.

Miller prepared himself for the worst: “It seemed improbable that anyone would employ, as a weather forecaster, an idiot who issued a tornado forecast for a precise location,” he later wrote. “I wondered how I could manage as a civilian, perhaps as an elevator operator.”

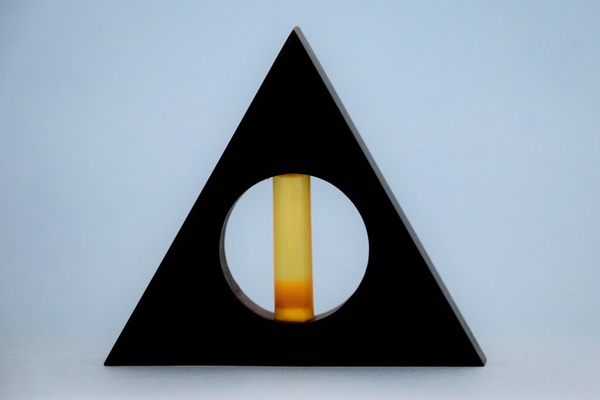

Modern-day tornado researchers are aided by more sophisticated equipment, like this Doppler On Wheels. (Photo: Center for Severe Weather Research/Wikicommons Public Domain)

Their forecast turned out to be correct, and when word of the feat got out a couple of years later, civilians clamored for their predictive wisdom. In 1950, the chief of the Weather Bureau backpedaled on the ban in an internal memo, writing “the forecaster (district or local) may at his discretion mention tornadoes in the forecast or warning.”

These days, tornado forecasting is still hard to pull off–“we don’t fully understand” how they work, writes Edwards. But thanks to technological advances, changing priorities, and ever-more-detailed science, the average annual tornado death toll has gone down significantly since the 1950s (though some storms, like 2011’s Joplin, still kill hundreds). It helps, of course, that forecasters no longer have to twist away from the word.

Update, 2/11: The original version of this article said that “no single tornado has killed over 100 people since 1953.” This is incorrect–a tornado called Joplin killed 161 people in Missouri on May 22nd, 2011. Thanks to Doug Heady for the correction, and we regret the error.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook