Keeping the Centuries-Old Tradition of Venetian Bookbinding Alive

Inspired by a 15th-century editor, Paolo Olbi pushes to keep this from being the last chapter.

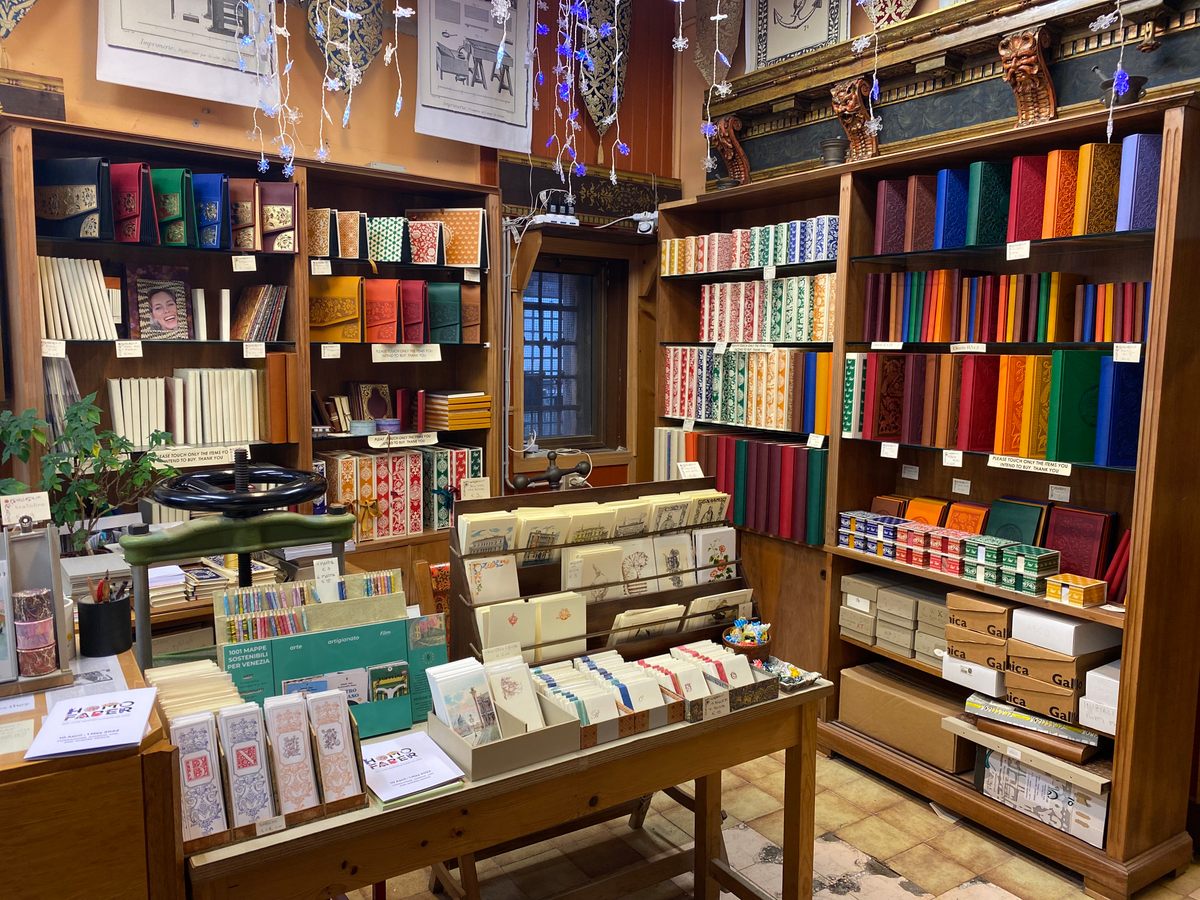

The first thing one notices upon approaching Paolo Olbi’s bookstore from Ca’ Foscari bridge in Venice is the intricate patterns and vibrant colors. His carefully displayed selection of handmade books, notebooks, and stationery look like an old postcard. Olbi himself, an impeccably dressed and groomed 78-year-old native Venetian, is as much a caretaker as an artisan.

“I started learning handmade bookmaking at 18,” he says. “And 60 years later I am still loving it.” The books for sale at Olbi’s store are traditionally hand-bound, using techniques that can only be learned through apprenticeships with masters of the form. When he started in this trade, there were around 20 traditional bookbinding shops in Venice. Today, he is one of just three.

At his workshop, Olbi overlooks all the steps of traditional bookbinding, from cutting each page out of large sheets of paper to printing designs with unique molds. Olbi’s covers might be made from wood, Murano glass, or even ceramic tile. “I am loving what I do but I wonder who will carry on all of this when I am gone?”

The printing press was invented by German goldsmith Johannes Gutenberg in 1449, at least in Europe—printed books dating to 1234 in Korea suggest that the printing press was already in use in Asia by that time.

It was in Venice that Gutenberg’s invention really took off. “Venice became the most important city for the printing industry in the first century since the printing press was invented,” says Rosa Salzberg, an Early Modern historian at the University of Trento. “Prospective bookmakers could find both the capital and the skills needed to make books here.”

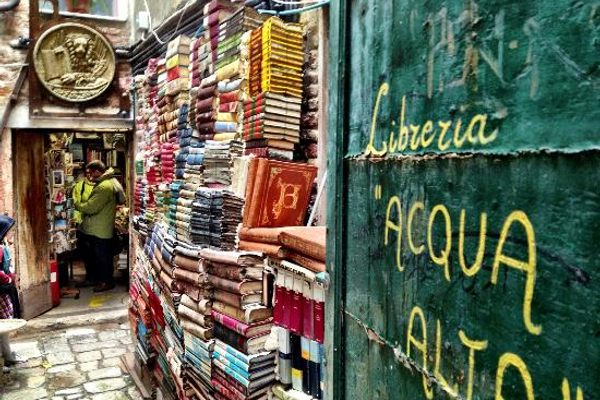

During the 15th century, printing defined much of Venice’s street life. As explained by Alessandro Marzo Magno in Bound in Venice: The Serene Republic and the Dawn of the Book, the city’s tiny calles (streets) were filled with the workshops of various craftsmen involved in the book industry. People interested in creating books went there to buy loose sets of printed pages, and then took them to binders, illustrators, and goldsmiths to create a volume. There were no set prices. Bargaining was the order of the day in what Marzo Magno describes as a “Middle Eastern souk.” By the 16th century, half of Europe’s print shops could be found in La Serenissima (the Most Serene Republic, that is, Venice).

Several factors had turned the Republic of Venice into Europe’s printing capital. As Marzo Magno explains, the city was home to investors willing to put capital in new risky ventures and was strategically located near paper mills that harnessed water power from Alpine rivers. Unlike many other cities, Venice was free of censorship (at least until 1553), which allowed for virtually any manuscript to be published. And it was relatively open to foreigners and people of different religious backgrounds, something that led to innovations in typography to accommodate different alphabets. It was there that the first ever printed versions of the Talmud and the Qur’an were created.

Venice became famous for both the sheer number of books created there and “the richness and the beauty of the volumes its printers produced,” Marzo Magno notes.

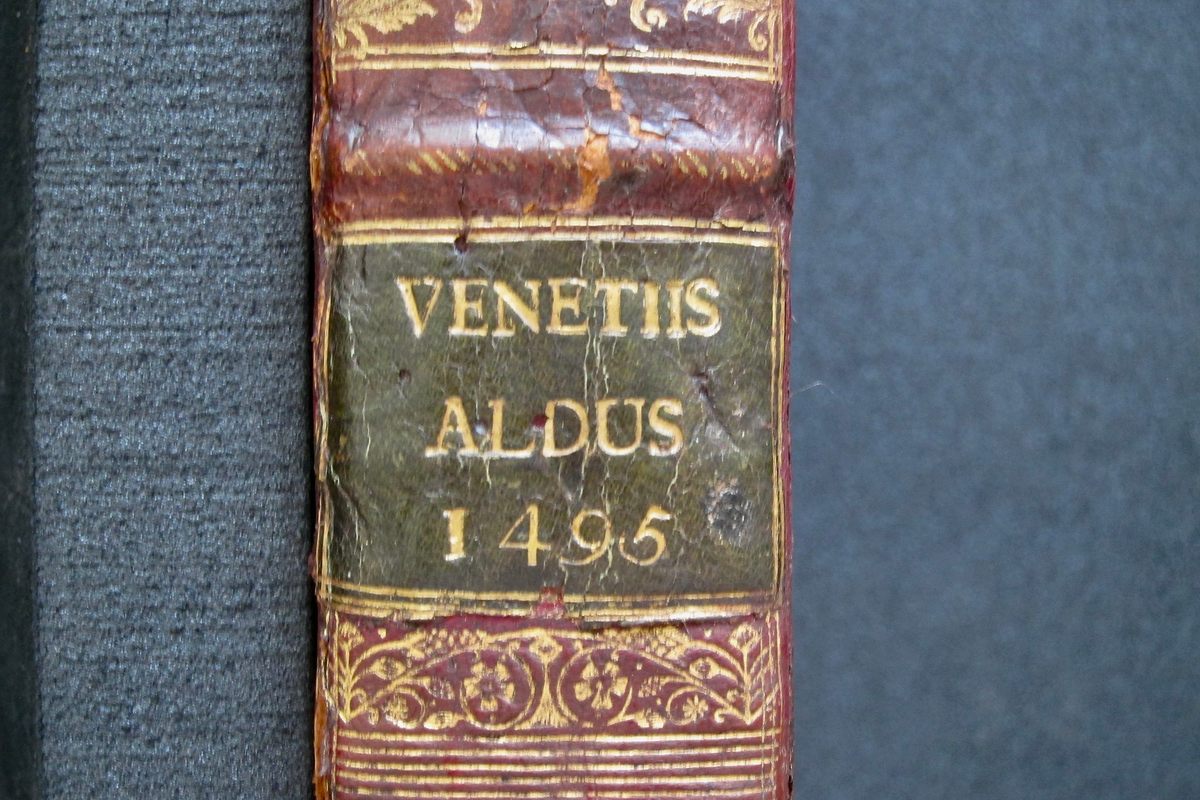

Indeed, one of the defining innovators of Venetian printing industry was an immigrant himself. Aldus Manutius was born in 1452 in the Vatican. A classically educated man, he worked for some years as a private tutor for noble families in central Italy. But when he heard about the printing press, he left that career to start a venture in the Republic of Venice. Founded in 1494, the Aldine Press became one of the most innovative printing businesses of its time.

“Books in the first decades of print tended to reproduce conventions of the manuscript book, or codex,” says Christopher Barbour, curator of rare books at Tufts University. “By contrast, Manutius popularized smaller books that could be taken out of the library and fonts that were easier to read, such as the italic type.” And while most early printers focused on religious texts or legal documents, Manutius was the first to focus on Latin and Greek texts, according to G. Scott Clemons, an expert on Manutius and the Aldine Press. The press was the first publisher of Aristotle, Euripides, Sophocles, or Herodotus, and Manutius was sometimes known as “the savior of Western civilization” for the way he saved ancient texts from the risks of wear and tear that came with handmade manuscripts.

Olbi’s first encounter with this ancient bookbinding tradition happened when he was 12 years old. “My older brother gave me a second-hand adventure book by [Emilio] Salgari as a gift,” he says, referencing one of Italy’s most translated authors. “I immediately started to fix its broken cover.” Olbi’s love for covers is evident in his shop. A portrait of Manutius hangs over the shelves. “That man,” Olbi says pointing to the portrait, “loved books and thought that they had to be beautiful, and I think so, too.”

Making a book from scratch requires precision, craftsmanship and a deep knowledge of materials. First, pages are cut with a knife from large sheets of paper, always with the grain. Then each page is pierced with a needle to create a series of holes needed for sewing. Each page gets tied to the next with a thread made of cotton, hemp, linen, or nylon. The thickness of the thread determines the thickness of the binded pages. “Binded pages should be thick enough to fit naturally into the cover,” Olbi explains. “If they are too thick they won’t fit and if they are too slim they will slip away.” For a typical volume about the size of a paperback, the ideal thickness is usually two millimeters. “If you do your job right, binded pages should fit like a tailor-made coat,” Olbi says, adding that he only glues the cover to the first and last page of the book while the remaining pages simply “rest” on the spine.

To make a cover, Olbi uses a rounded knife to cut cardboard for the “skeleton.” He then picks a material for the exterior, usually paper, textile or leather and sometimes more exotic materials like tile or glass. “Paper covers are the easiest to make,” he says. “I select the type of paper, make a drawing by hand, color it, cut it and attach it to the cover with PVA glue.” Leather covers are harder. First, the leather needs to be cut to fit the cover, which can be tricky, and then, designs are pressed into the leather with hot molds.

If gilding is involved, the process can take longer. First a design is imprinted into the cover, then the pressed design is covered with a wash of water and egg white. Gold leaf is then placed and pressed with a hot mold. The remaining leaf is then removed with a piece of cotton.

According to Olbi, the hardest part of the process is choosing the right materials. “If you pick the right materials and cut them the right way, working is fun,” he says. “But if you realize down the line that a piece of leather is too hard or a thread too thick, it gets tricky.”

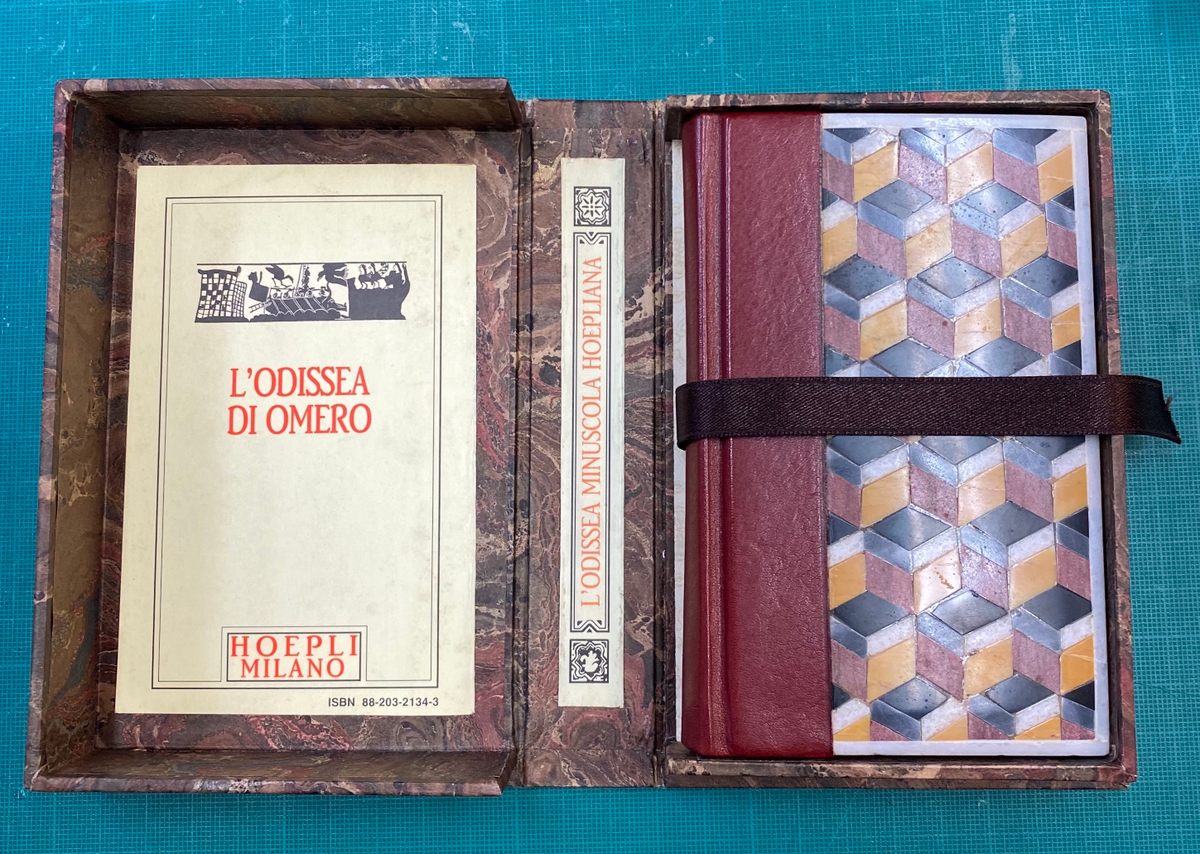

Some of Olbi’s favorite creations employ unique materials. In a drawer by the till, he keeps two pocket-sized books. One, a handmade copy of Dante’s Divine Comedy, is made with Murano glass, and the other Homer’s Odyssey, is made with 220 small marble pebbles from Saint Mark’s Cathedral. “It took me weeks to make the Murano glass cover,” he explains. “This type of glass is thin like a cracker so I had to be very careful not to break it.”

Olbi sells books every afternoon at his shop, but he spends his mornings in his workshop inside the 17th- and 18th-century Palazzo Ca’ Zenobio, in the Dorsoduro district. The three rooms on the ground floor that host Olbi’s workshop smell of ink, paper, and humidity. The first room is filled with different kinds of paper, from hemp to silk. A shaky door leads to a second, larger room, filled with 19th-century movable-type printing presses that must be operated manually. A wooden closet with many drawers hosts different sets of individual letter blocks in various fonts, from the Manutius-invented italic to Gothic styles. When printing texts, Olbi and his collaborators recreate paragraphs and pages by placing each letter block on the composing block of printing machines—hence, movable type. Each sheet of paper is then passed through the machine to be imprinted.

Olbi usually takes care of binding himself, and acts as a project manager for the efforts of binders, typographers, illustrators, and gilders. Whereas ancient Venice was a souk of purveyors, Olbi’s is a one-stop shop. The length of each project varies, from half a day for a blank notebook to nearly a month for elaborate printed volumes.

Most of the books Olbi sells today are those blank notebooks or albums. They sell well and don’t take long to produce. Printing books with text is very labor intensive, and Olbi only makes those for specific commissions. “Every year with Ca’ Foscari University we choose a poet and we print works by that author,” he says. “While next year I am going to print the works of an Armenian poet that was commissioned by the Armenian congregation.”

In his workshops, one can see just how daunting a task printing was in its early days, even with Gutenberg’s innovations. It’s a bit like comparing a room-sized 1950s computer with a modern smartphone. “Printing was cutthroat and expensive,” says Clemons. “Some publishers would publish one book and go out of business.”

In Venice’s golden age of printing, it took great dedication, along with luck, to stay in business. The Aldine Press is one of the few ones that made it. “Manutius was both a scholar and an entrepreneur,” Salzberg says, noting that other printing ventures were often run by scholars who lacked business skills or investors who only cared about profits. Manutius’s connections with royals and intellectuals—he was friends with Erasmus from Rotterdam—helped. “Before Manutius, printed books were considered a new innovation that scholars could use,” Salzberg says. “But he framed them as something that anyone interested in literature should own.” Thanks to his influence among the literate elite, he helped put Venice, which had not been considered a cultural hub during the Renaissance, on Europe’s culture map.

Today, Olbi is having a hard time keeping his publishing venture afloat, sometimes literally. “When water from the canal overflows we need to quickly move everything off the floor,” he says. One time the water rose to the level of the tables and damaged a lot of materials. Dealing with bursts of acqua alta (tide peaks) is not the only challenge that comes with running a traditional bookbinding shop in Venice. “It’s very hard to retain talent here,” Olbi says. In the past the local government financed traineeships in traditional crafts, but funds have dried up. And even when students pay for their own training, they eventually have to leave Venice due to its unaffordable housing. When Olbi speaks of former trainees, his eyes sparkle. “Some of my apprentices were so talented,” he says. “It is a joy for me to see young people taking on Manutius’s love for books.” One of his talented trainees, Anna Scovaricchi, spent six months with Olbi thanks to a regional government scheme in the early 2010s. She now runs her own bookbinding workshop in nearby Padua. “Sadly, Venice is not a good place for young creatives,” she says. “Housing is expensive and it’s really hard to find space for workshops.” Padua, by contrast, provides artisans with space.

Olbi would like to pass the baton—there, in Venice—to people such as Scovaricchi, but time and again his trainees end up leaving the lagoon. “In the past 10 years, landlords prefer profitable short-term rentals like Airbnb over longer-term ones for students or young workers,” he says. “And the government does not give any incentives for people taking on traditional crafts.”

Despite the challenges, Olbi continues working and leading a network of bookbinding enthusiasts. “We would like to turn some rooms of Ca’ Zenobio into a cultural center,” he says. “It would be called ‘Aldine School.’” In his vision, the school would operate as a bookshop, workshop, and cultural center, where visitors can meet with artisans and authors. Olbi is currently in talks with Samuel Sarkis Baghdassarian, cultural affairs manager of the Armenian community in Venice, to realize the project.

But as is often the case in Italy, bureaucracy is standing in the way. “Ca’ Zenobio currently does not have permits to host a center open to the public,” Baghdassarian says. He is currently trying to obtain the required papers, but for now he is running workshops and lectures on bookbinding at Palazzo Pisani-Revedin, in the Saint Mark’s neighborhood. “This summer we will be hosting workshops with students coming from Boston,” he says. “There is definitely interest in this both in Italy and abroad.

“Sometimes foreigners are more interested in preserving Venetian traditions than locals,” Olbi says, in reference to a project called “Venice in Peril,” led by Lady France Clark, wife of the late British consul of Florence, who has led initiatives to protect Venice monuments from flooding. “It’s part of the city’s cosmopolitan nature.” His hope is to channel the interest of traditional bookbinding appreciators from around the world to support the preservation of the craft. “I would like for the world’s leading center on bookbinding to be here,” he says. “In the city of Manutius.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook