What Animal Has the Weirdest Heart?

There’s a lot of competition.

Sure, the human heart is a wonder—it keeps us alive, it’s literally electric, it’s the metaphorical seat of the soul, and so on. But can it regenerate itself? Does it pump exclusively clear blood? Can it freeze and then come back to life?

Some animal species’ hearts can do this and more. We scoured the animal kingdom for cardiac marvels, from the depths of the ocean to the top of the Himalayas. Here are some of the strangest we found, divided into categories for your convenience.

Bugs

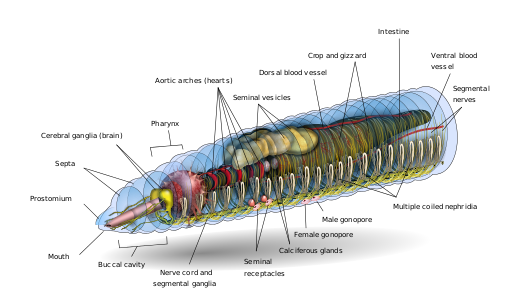

Earthworm

Depending on how you define your terms, earthworms either have five hearts, or no heart at all. While they lack the chambered, muscular organ that normally comes to mind, they do have five special blood vessels, called aortic arches, that contract in order to pump blood through the worm’s body. Look really closely at a specimen, and you can see the arches squeezing and releasing. So if you break an earthworm’s heart, don’t worry—it has four more.

Cockroach

A human heart has four chambers, each with a specific job—if any of them fail, it’s bad news. A cockroach heart, on the other hand, has 12 to 13 chambers, all arranged in a row and powered by a separate set of muscles. This built-in redundancy means that if any one chamber fails, the cockroach is barely affected. We humans have been outmatched once again.

Marmalade Hoverfly

Marmalade hoverflies like to linger in the air over flowers, harvesting as much pollen as possible in one trip. To do this, they’ve evolved what is essentially a one-track heart—it spends almost all of its time and energy pumping blood forward into the head and thorax, where the wing muscles and mouthparts are. The abdomen gets only the occasional kickback, when the heart would otherwise be resting.

Fish & Their Neighbors

Zebrafish

Sure, the zebrafish looks like your average pet store minnow, but under that stripy exterior beats what is, effectively, a superhero’s heart. In 2002, scientists discovered that if you cut out up to 20 percent of the zebrafish’s lower ventricle, they regenerate all that lost tissue within a couple of months. This happens thanks to specialized muscle cells that not only promote their own growth, but jumpstart the production of new veins. By studying these self-healing hearts, researchers hope to eventually apply their strategies to human organs.

Ocellated Icefish

Ocellated icefish live about a kilometer down in the Southern Ocean, which is the one next to Antarctica. How do they cope with the cold? Partly thanks to their tickers, which are much larger, and about five times stronger, than your average fish heart. Their blood also lacks hemoglobin, the red protein that normally binds to oxygen—instead, thanks to the low temperatures, oxygen is dissolved directly into their plasma. Because of this, they have clear blood. Icefish indeed.

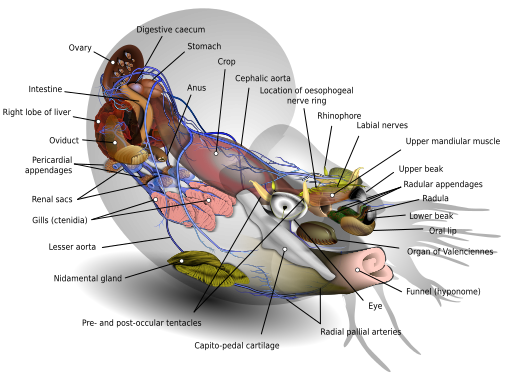

Cuttlefish

Like all cephalopods, the cuttlefish has three hearts—one for each gill, and a third for the rest of its body. Research has shown that cuttlefish in cold waters have larger hearts than those in warmer waters, to enhance aerobic capacity. They also have hemocyanin instead of hemoglobin in their blood, which means that their blood is blue. Very aristocratic.

Birds

Blue-Throated Hummingbird

You’ve probably heard that hummingbirds flap their wings 15 times per second—so fast that the human eye just sees a blur. Enabling that wingspeed is an even faster heart, which in the blue-throated hummingbird has been measured revving up to 21 beats per second. This efficiency helps enable the hummingbird’s unparalleled ability to bring oxygen to its muscle mitochondria, which researchers say “may be at the upper limits of what [is] structurally and functionally possible” for vertebrates.

Bar-Headed Goose

Migration is tough on every bird, but the bar-headed gooses’ route is particularly taxing—they head straight over the Himalayas. Flocks are regularly observed winging it through mountain passes about 20,000 feet above sea level, powered by unusually strong hearts, which are connected to the flight muscles by super-organized sets of extra capillaries, and can pump five times faster in flight than at rest. They’re also able to hyperventilate without getting dizzy, which helps.

Emperor Penguin

Emperor penguins are famous for the softness of their hearts. Serial monogamists, penguin couples spend most of each year tending each other, their eggs, and their chicks. Less well-known, but equally important, is the slowness of their hearts. While diving, emperor penguins can dial back their heart rate to about 15 beats per minute, shutting off blood supply to all but the most vital organs and doling out only as much oxygen as is necessary for deep-water hunting. And when they come back up, they do so at a sloping angle, like a scuba diver avoiding the bends.

Reptiles & Amphibians

Wood Frog

Plenty of animals, from bears to groundhogs, slow down their hearts when hibernating—but as far as we know, only wood frogs can stop the beat completely. During the winter, these frogs essentially become frogsicles: thanks to special solutes in their cells, they can halt metabolic activity and allow most of their body water to solidify, all without any lasting damage. Their hearts take it in stride, stopping when the world freezes and starting again when it thaws out.

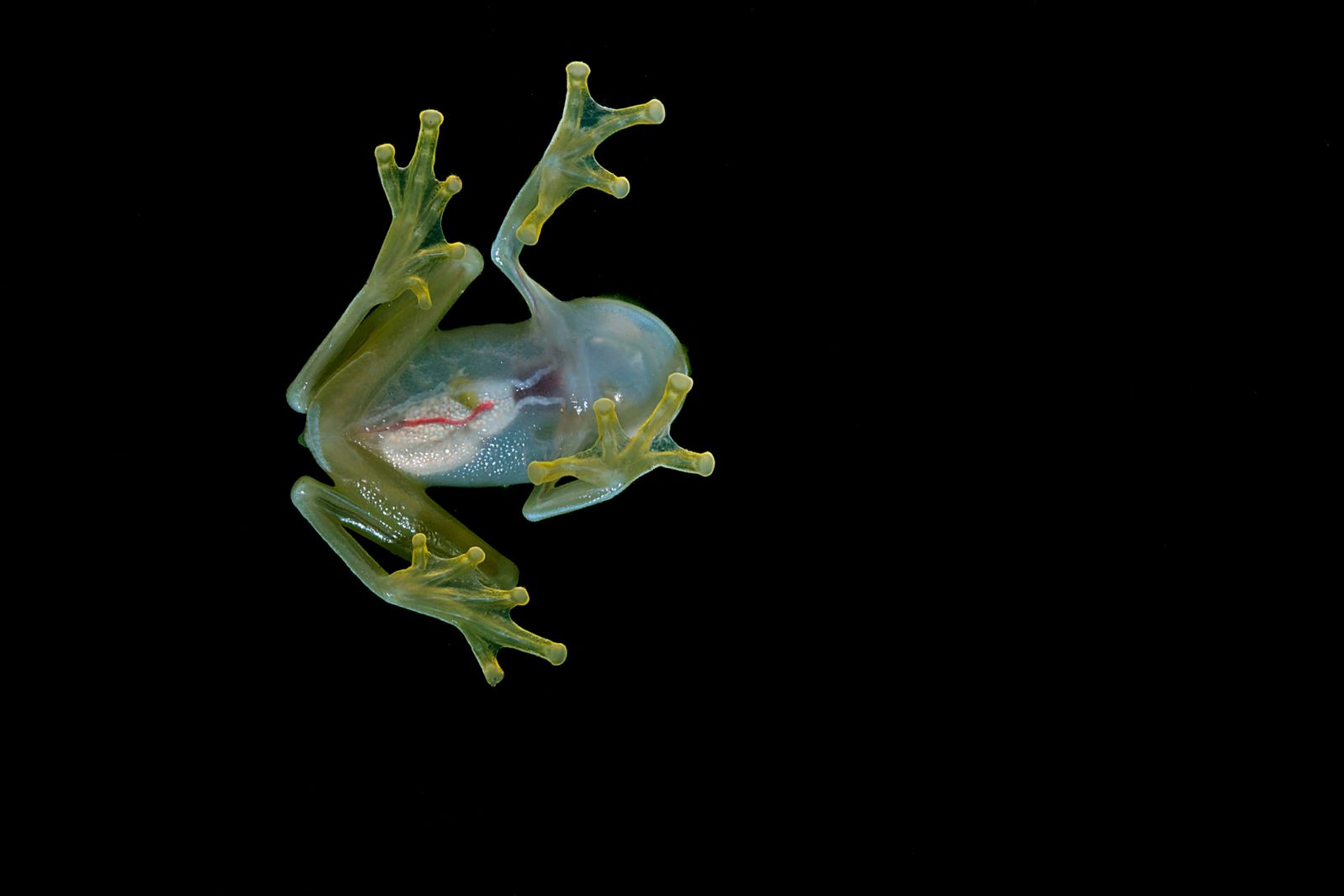

Glass Frog

All frogs have three-chambered hearts, with two atria, which receive blood from other parts of the body, and one ventricle, which shunts it back out again. Glass frogs are unique in that you can actually see this happening—their translucent abdominal skin provides a great view of the heart at work, as well as the blood vessels snaking through its other organs.

Python

If a human heart is filled with fat, there’s cause for concern, but if it’s a python heart instead, things are going great. After one of its famously giant meals, a python’s heart increases in size by about 40 percent, swelled up by fatty acids absorbed from the meal. (This speeds up digestion, which still takes days.) Its blood gets so full of the fatty acids, it turns opaque—“like milk,” researcher Leslie Leinwald told National Geographic.

Mammals

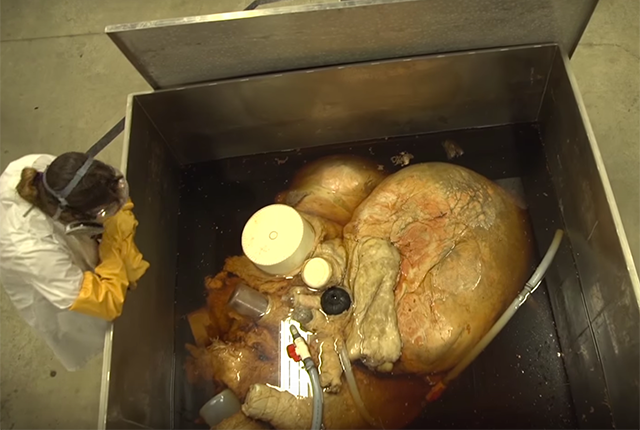

Blue Whale

Popular legend holds that a blue whale’s heart is as big as a car, and that a human could crawl through its aorta. This isn’t quite true—those that scientists have on hand are closer to “the size of maybe a small golf cart or a circus bumper car for two,” and the aorta could barely fit a human head, as scientist Jacqueline Miller told the BBC in 2015, after dissecting one. Still not too shabby, though.

Giraffe

You know those carnival games where you hit a lever and, if you’re good, the target shoots six feet up into the air? A giraffe’s heart has to do that all day, every day, fighting the pressure of gravity to get blood up to the head. He manages this by having extra-thick, extra strong cardiac walls, and blood vessels that expand and contract quickly and easily. The blood vessels also get thicker as the giraffe’s neck gets longer, so that they don’t collapse under the increasing weight.

Cheetah

A cheetah’s resting heart rate is around 120 beats per minute, about the same as a jogging human’s. But while the human heart rate tops out around 220—and takes a little while to get there—the cheetah’s heart skyrockets to 250 BPM in a few seconds. This ramp-up is so intense that it limits the cheetah’s sprinting time to about 20 seconds, after which her organs would become so hot they’d be permanently damaged.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook