Those Mass-Produced Civil War Statues Were Meant to Stand Forever

The company behind one popular cookie-cutter statue advertised they would “last as long as the Pyramids of Egypt.”

In 1898, the people of Elberton, Georgia—like those of many Southern towns a few decades after the Civil War—commissioned a granite statue to honor those local men who had fought for the Confederate army. Two years later, late one night, those same people took their own monument down. Public opinion of the war hadn’t shifted much: the statue was just ugly, with bug eyes, and what looked suspiciously like a Union-style overcoat. The citizens had nicknamed it Dutchy, because it resembled, one said, “a cross between a Pennsylvania Dutchman and a hippopotamus.”

According to the Elberton Star, on August 13, 1900, around midnight, a group of men tugged Dutchy down via “a rope around his neck.” A few days later, they buried him. And after they’d dusted themselves off, what did they do? They ordered a brand new “white bronze” statue from Monumental Bronze Co.—because one of those, they had been told, would last forever.

Today—117 years later—Dutchy’s replacement still stands. (It has been moved several times, and is now at Confederate Memorial Park, in Lee County.) A bunch of his Confederate clones still stand, too, in town squares and courthouses across the American South, while their Union brothers, in slightly different uniforms, remain stationed all around the North.

As recent events have reminded us, many of the South’s Confederate monuments went up not immediately after the war, but half a century later, in the first two decades of the 1900s. During this time, organizations like the United Daughters of the Confederacy were looking to reframe and glorify the Confederate cause, and in many states, the descendants of slaves had been stripped of the right to vote, which impeded their ability to effectively voice opposition.

Today, historians argue that the rush to erect Civil War statues, especially in former Confederate states, was part of that project. “It is hardly coincidence that the cluttering of the state’s landscape with Confederate monuments coincided with two major national cultural projects: first, the “reconciliation” of the North and the South, and second, the imposition of Jim Crow [racial segregation laws] and white supremacy in the South,” writes historian W. Fitzhugh Brundage, at Vox. By memorializing the dead in this particular way, Brundage argues, those who put up statues sought to reframe the story of the war, “making the Confederate cause virtually sacred.” In the spirit of peacemaking, Northerners went along with it, and put up their own statues, too. These goals may have been political, but the means were material: they almost certainly couldn’t have gotten so many statues up, in the North or South, without white bronze.

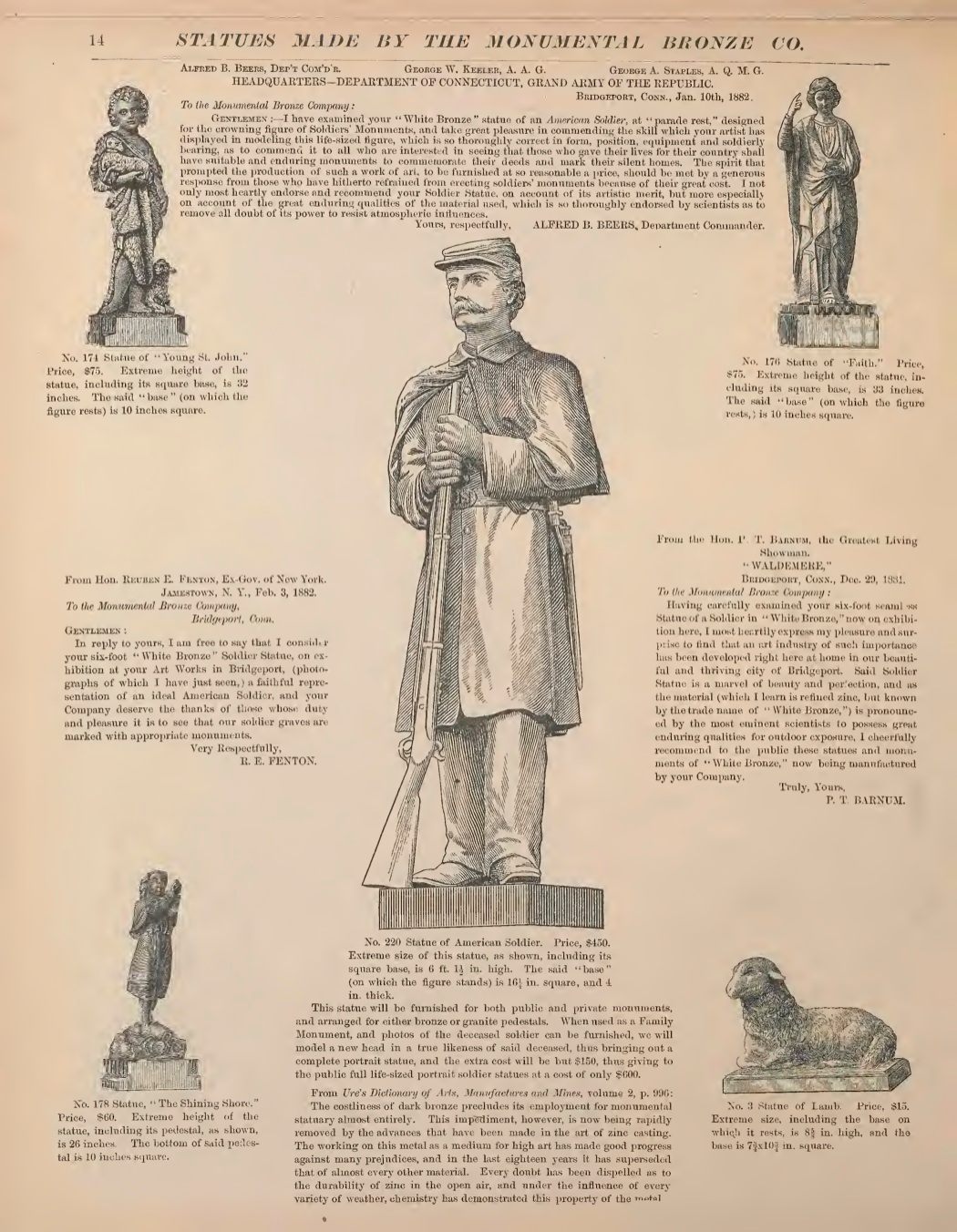

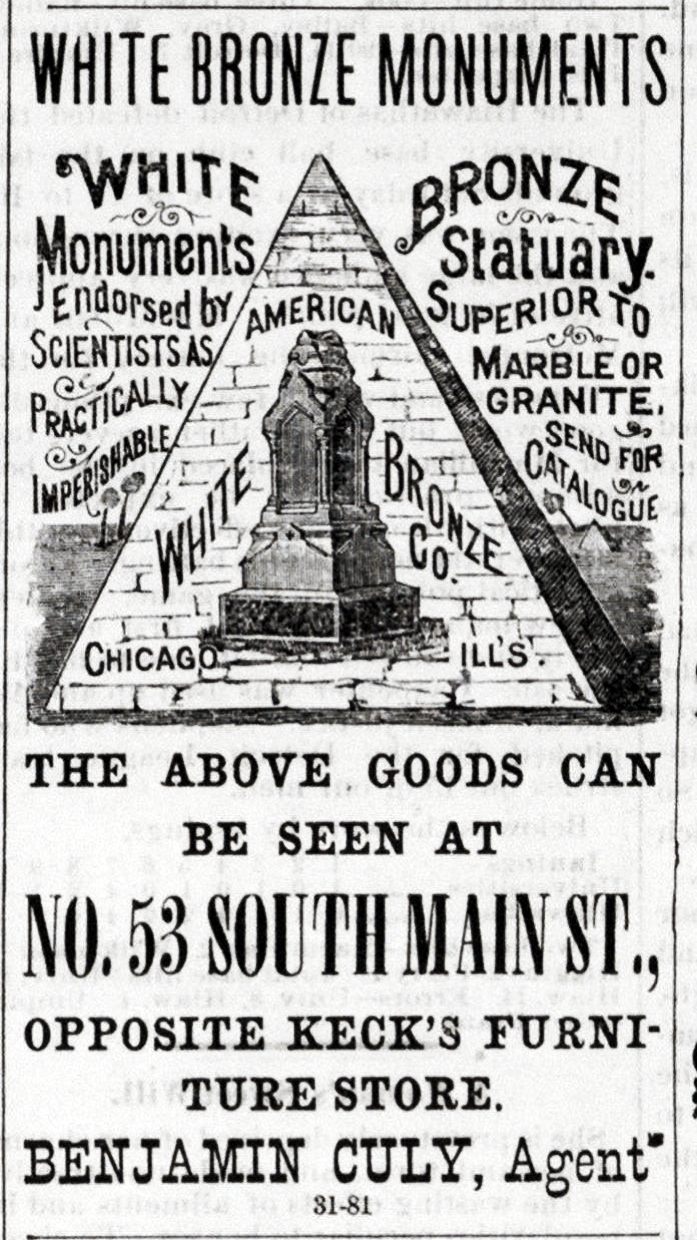

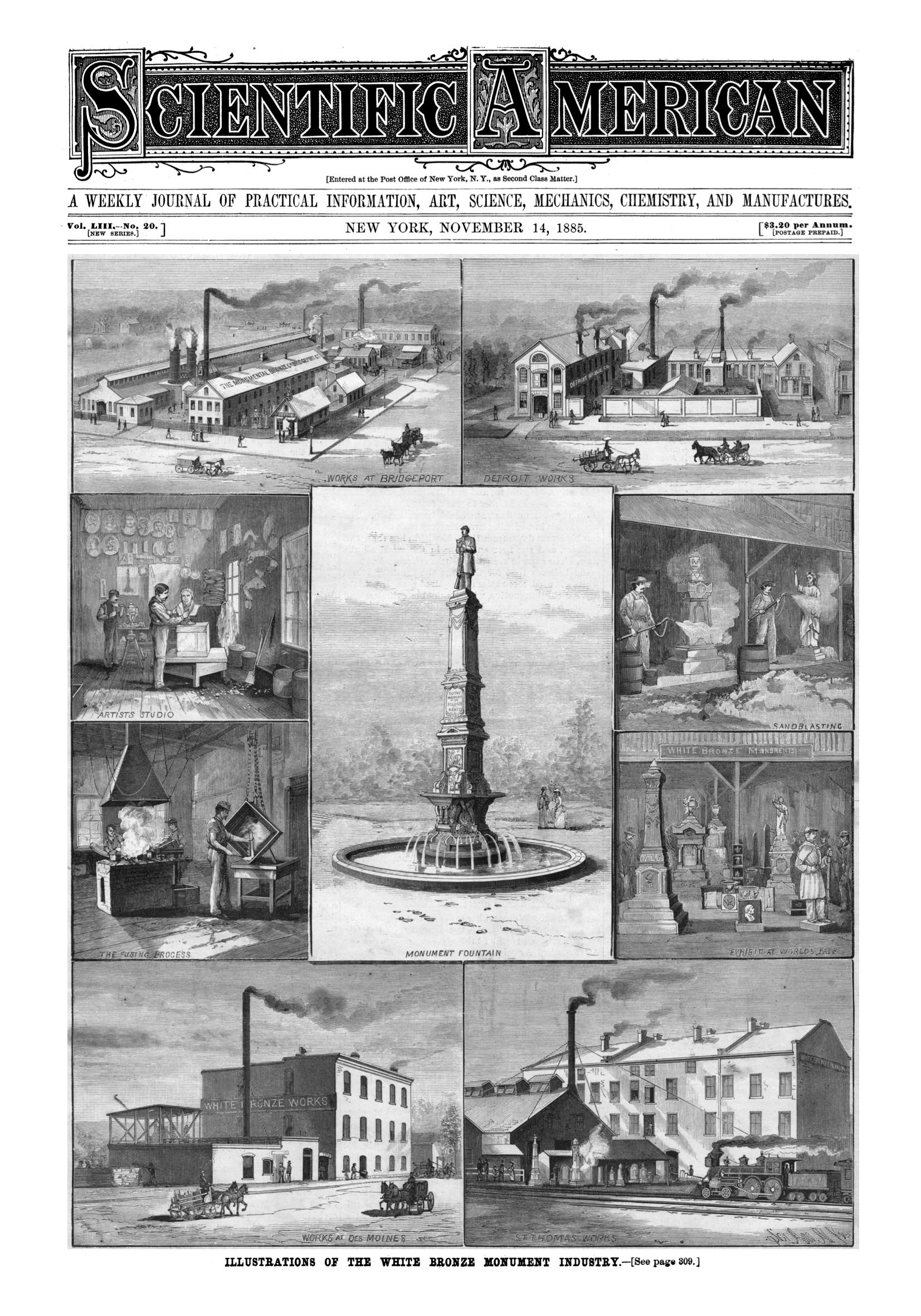

White bronze isn’t white. It’s more of a chromy gray that, over time, gets progressively blue. It isn’t bronze, either: it’s zinc, cast into shape in a mold, and blasted with sand to add a rough, stony texture. But “bluish-gray sand-blasted zinc” doesn’t sound that appealing, and the company trafficking in this material, Monumental Bronze Co., of Bridgeport, Connecticut, was focused hard on selling it. From 1879 until 1914, Monumental Bronze Co. offered statues, grave markers and monuments that were, in their words, “beautiful in appearance and unequaled for durability.”

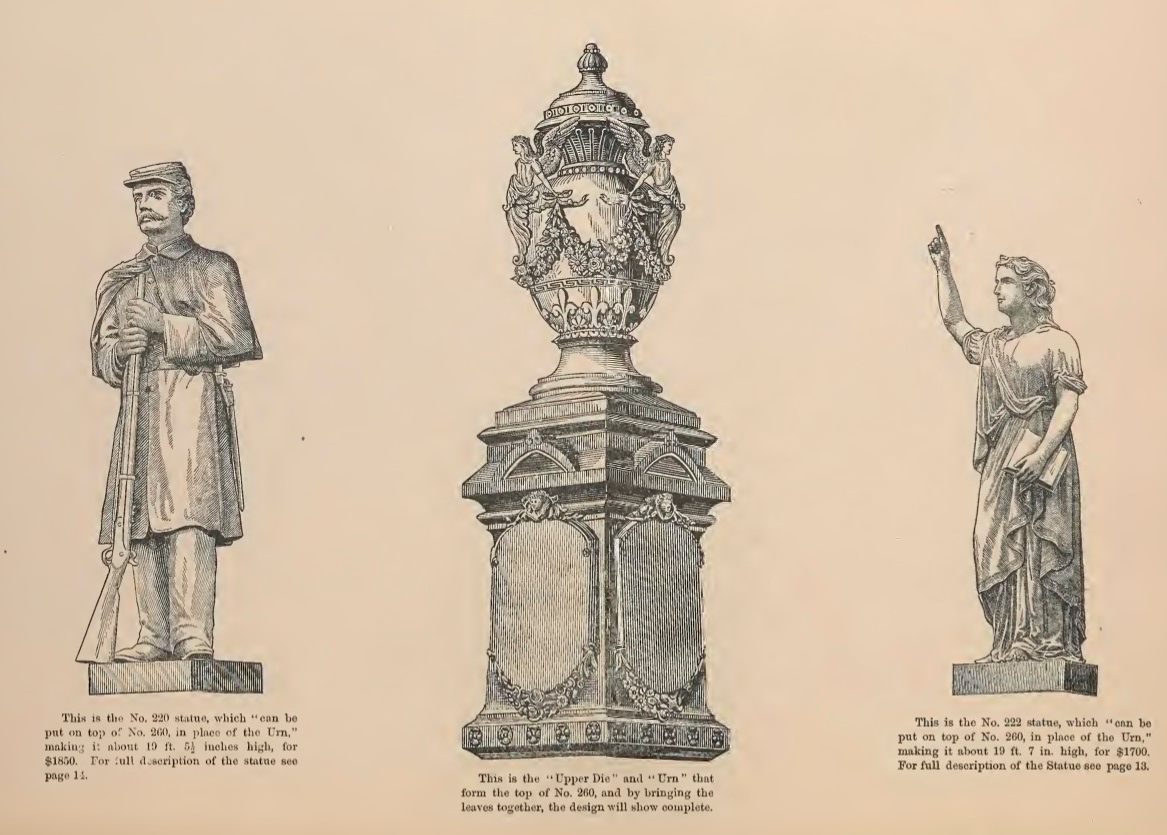

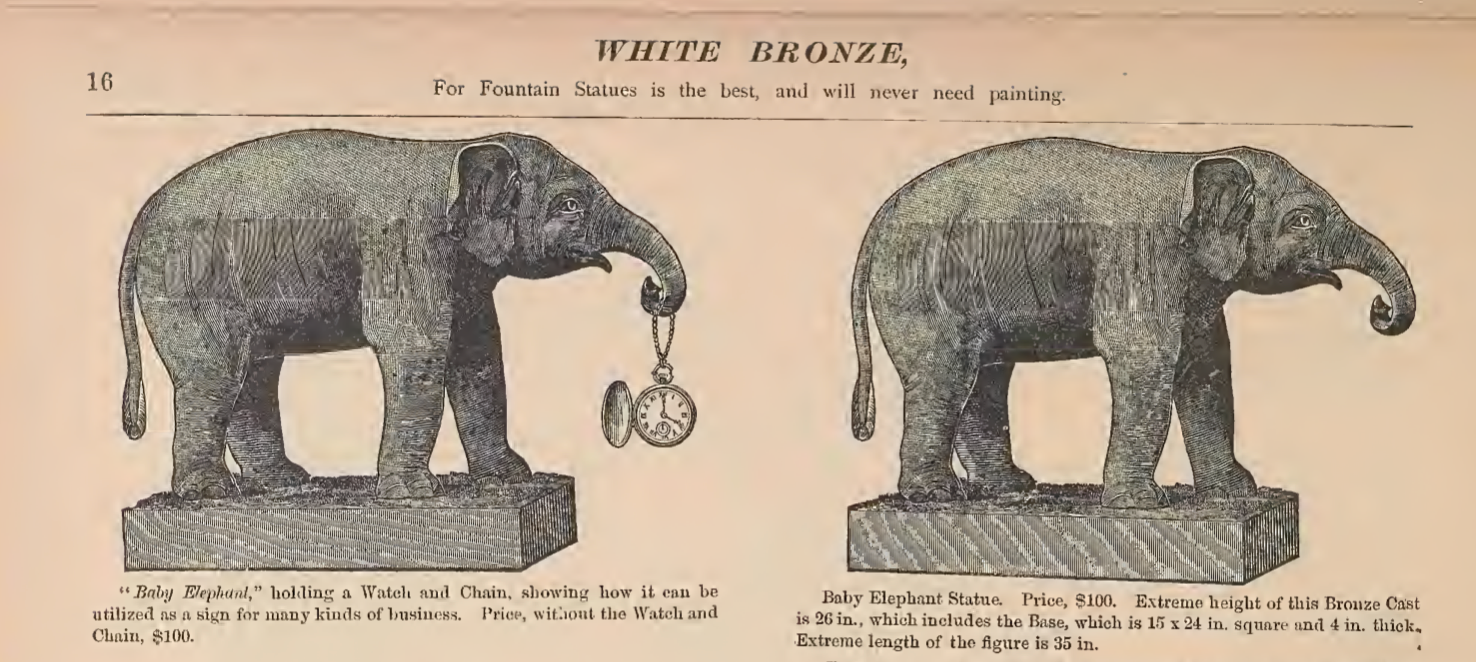

There were plenty of such businesses around at the time—death is certain, after all. But as the Associated Press reported in 2015, Monumental Bronze Co. set itself apart from its competitors in three ways. One was variety: customers could get an urn-topped pillar, a St. Joseph, or an elephant holding a bushel of cigars, each one on a pedestal with four fully customizable panels. (“It [was] like going to Wal-Mart,” monument expert Timothy S. Sedore told the AP.)

They also had a whole muster of Civil War statues in various designs, the parts of which could also be easily interchanged, Mr. Potato Head-style. “Statue of American Soldier” was a man with a mustache and a billed cap, holding his gun in both hands. “Colorbearer” had a flag draped over his shoulder. “Confederate Soldier,” introduced in 1889, wore a broad-brimmed hat and carried a bedroll. You could also get your soldiers custom-made: the Confederate Monument in Portsmouth, Virginia has four Monumental Bronze Co. statues on it, each fashioned after a local man.

Another of their selling points was price: thanks to their choice of material (as well as their distribution model, which relied on independent “agents” and eliminated the need for storerooms) they could easily undersell stone-based companies. In 1890, a “life size” soldier from Monumental Bronze Co. would set you back $450, the equivalent of $12,000 today—tough, but doable, especially if the whole town was chipping in.

But their third claim to uniqueness—and the one that, judging by their advertising strategy, was deemed the most appealing—was that white bronze. More specifically, it was the material’s supposedly peerless endurance. When zinc is exposed to air, a thin patina forms over it, which protects it from weathering. Page through Monumental Bronze Co. documents, and all you see is tales of the metal’s immunity to all of time’s ravages, both physical and spiritual. Stone will crack, crumble, and get mossy, they argue. White bronze will not.

“The most durable material of which monuments or statuary are made,” promised one advertisement. “Marble is entirely out of date, [and] granite… requires constant expense and care,” asserted another. “Many granite dealers have bought White Bronze for their own burial plots.” In a broadsheet themed around run-down national monuments, the company asked, “Will the American people ever learn that NO STONE, no matter what it is, can withstand the rigors of our northern climate?” And while said stone came in various grades, they wrote, “In White Bronze there is but one quality (the best).”

In print advertisements, customer testimonials to this effect are stacked as high as the illustrated obelisks next to them. Many paint an image in which all history crumbles, save for the parts mankind was savvy enough to cast in white bronze. One, detailing a scene at San Francisco’s Presidio Army base, is particularly stark: “The White Bronze Soldiers’ Monument… looks as majestic as ever,” it reads, “while all around lie large marble and granite monuments, cracked and broken.”

The company even snuck this claim into their signoffs —at least one mailing ends with the valediction, “Yours for Artistic and Ever-Enduring Memorials, The Monumental Bronze Co.” “Please preserve this card,” reads another, its choice of verb clearly deliberate.

Along with the good reviews and morbid rhetoric, the company also brought out some bigger guns: scientists. Metallurgists, government chemists, and other experts were apparently eager to predict, with varying degrees of preciseness, how long a white bronze statue might stand. “I can see no good reason why these monuments should not last as long as the Pyramids of Egypt,” wrote Professor J.W. Armstrong of the New York State Normal School. Others went with “thousands of years,” or simply “ages.”

Weather and vegetation could also try their worst: “It will not be altered by the action of any constituents of the atmosphere,” wrote Professor E.P. Harris of Amherst College, “nor will it absorb the moisture and become coated with green, cryptogamous plants.” As one broadsheet sums up, “White bronze is endorsed by scientists. Stone is not.”

This marketing strategy clearly worked. Although specific numbers are hard to come by, the Monumental Bronze Co. thrived for decades, eventually expanding its operations to Detroit, Chicago, Ontario, and Louisiana. in 1921, the company’s home newspaper, the Bridgeport Telegram, reported that they were doing “enormous” business, “especially in the South and West.”

According to the company, their soldier statues, which they called “a specialty,” eventually appeared in 31 of the then-48 states. Newspaper items announcing their arrival, in cities and towns both North and South, are invariably positive—“The color is Confederate gray,” one reviewer, from Houston, enthused of the white bronze. To fund Portsmouth, Virginia’s massive Confederate Monument (the one with the four custom statues), the local Ladies Memorial Aid Association raised money for 18 years.

But the trend wouldn’t last forever. In 1914, World War I began, abruptly ending the Civil War statue boom. It also ended memorial-making at Monumental Bronze Co., as the government took over the company’s zinc foundries to cast gun mounts and munitions. The white bronze monuments, though, largely stood their ground, and many have to this day.

Although the heavier ones are prone to sinking, and some have turned bluer with age, there are still Monumental Bronze Co. Civil War soldiers in towns and cities from Maine and Vermont to Missouri and Virginia. Their inscriptions, experts say, remain especially legible—“every word, every name, every date is as clear … as the day it was cast,” write two genealogists from Pennsylvania.

At least, they’ve done so until now. When Monumental Bronze Co. wrote, in 1890, “when marble, sandstone and granite have crumbled to atoms, these monuments will remain untouched by the destroying hand of time,” they and the customers that listened to them weren’t taking into account the fact that more than one thing can fell a statue. Locals have been trying to take down that Confederate Monument in Portsmouth, Virginia for over a year, an effort that has gained new steam in recent weeks—and one of many such efforts now taking place across the country. Sometimes it’s not the material that’s the problem, but the message.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook