Oxpeckers Are an Early Warning System for Rhinos at Risk

As their name suggests, these small birds provide critical cleaning services to oxen, impala and other animals of the savanna—with a side hustle as rhino guards.

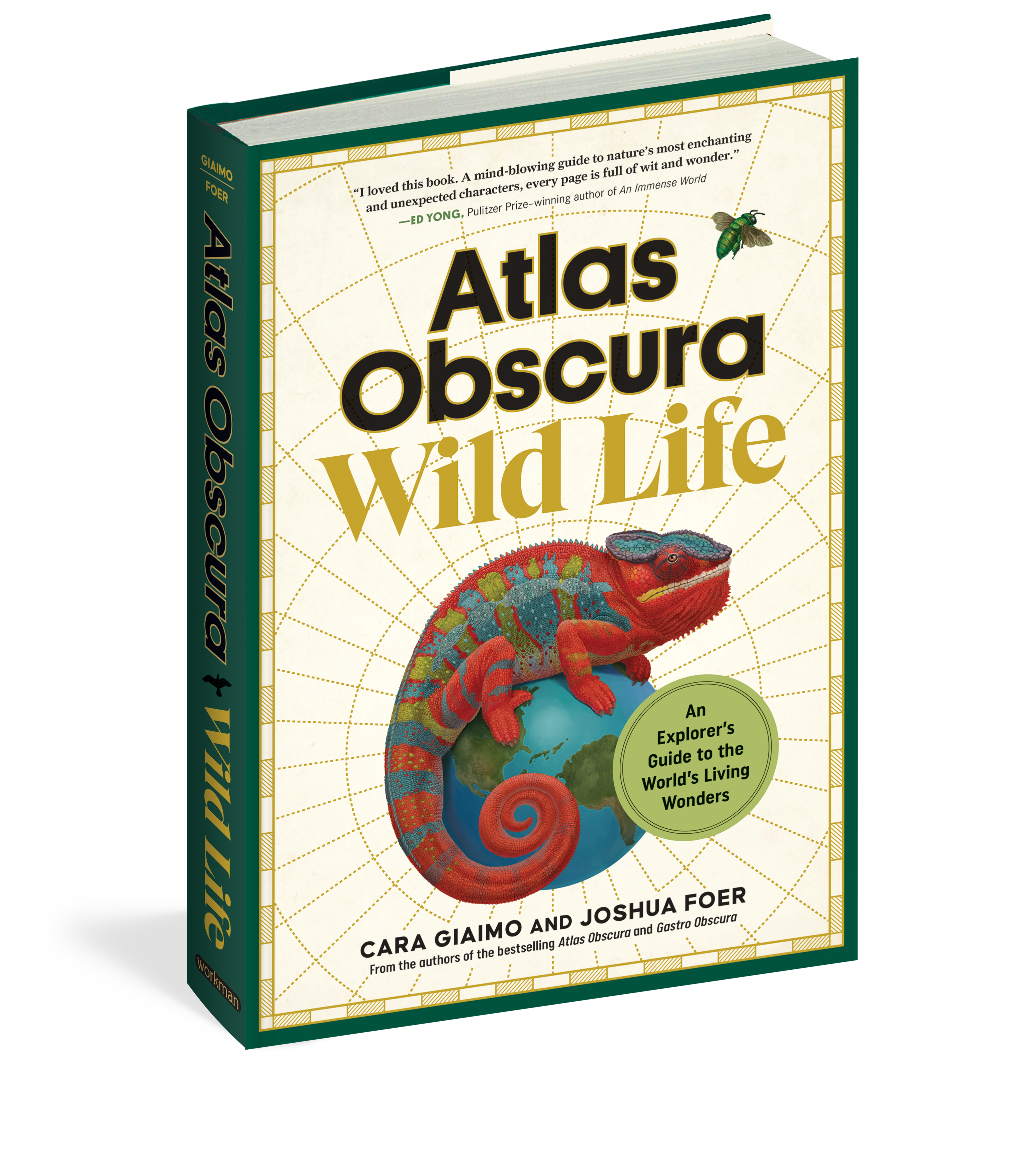

Each week, Atlas Obscura is providing a new short excerpt from our upcoming book, Wild Life: An Explorer’s Guide to the World’s Living Wonders (September 17, 2024).

Red-billed oxpeckers are named after their main trade: providing cleaning services to ungulates. A typical oxpecker spends her time perched atop oxen, impalas, and other savanna ruminants, pecking bugs out of their fur and skin (and sometimes their noses). She gets to eat, and her host is freed of itchy, dangerous pests. It’s a straightforward win-win transaction.

But for at least one species, the black rhino, the oxpecker’s service package includes another benefit: security. Although these gentle giants are too large for wild predators to eat, hundreds—sometimes thousands—are killed every year by poachers. Quiet, solitary, and nearsighted, rhinos depend on their oxpecker ride-alongs to warn them about encroaching threats.

Settled sentry-style on a rhino’s flank or horn, an oxpecker will stare at the horizon out of yellow-ringed eyes that look perpetually peeled. If she spots anything suspicious—lion, human, strange-looking cloud—she’ll let out a rough-edged warning call, “tseeeee.” In response, her mount will perk up and turn his attention to the threat.

Hunters and other observers have long noted this special relationship. (The oxpecker’s Swahili name, askari wa kifaru, means “rhino’s guard.”) More recently, biologists have begun to test its efficacy. It seems to be working: A 2020 study in which researchers attempted to sneak up on rhinos found that those with oxpecker lookouts were always aware of human approaches, while those without them caught on less than a quarter of the time. In these experiments, rhinos also noticed people from more than twice as far away as birdless ones, with each additional scout adding about 30 feet (9 meters) to the detection distance. “The rhino is absolutely eavesdropping,” says study author Roan Plotz.

In fact, the bird guards are so good at their jobs that they made it difficult for Plotz and his team to do theirs: They were rarely able to find rhinos with oxpeckers in the wild, he says. (They ended up focusing on rhinos that could be tracked regardless, thanks to radio transmitters in their horns.) A warned rhino will quickly turn to face downwind—more evidence that this response evolved specifically to protect from human hunters, who often approach from that direction.

In return for their vigilance, oxpeckers get meals on the job—not only ticks and other hitchhiking insects, but blood and pus from sores on the rhino’s back, made by parasitic roundworms and kept open by the birds as an iron-rich food supply.

The rhino’s willingness to put up with this might be more evidence that the relationship is worthwhile, Plotz says. Other large animals, like Cape buffalo, will throw themselves on the ground to get rid of an overzealously vampiric oxpecker. But a rhino doesn’t seem to mind giving a little blood to his eyes and ears.

- Range: Sub-Saharan West Africa

- Species: Red-billed oxpecker (Buphagus erythrorynchus); black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis)

- How to see them: Look for a bird with a bright red bill hitching a ride on an ungulate.

Wild Life: An Explorer’s Guide to the World’s Living Wonders celebrates hundreds of surprising animals, plants, fungi, microbes, and more, as well as the people around the world who have dedicated their lives to understanding them. Pre-order your copy today!

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook