Winter’s Effigies: The Deviant History of the Snowman

Dutch queen Wilhemina & princess Juliana as snowpeople in the Netherlands (1913) (via Nationaal Archief)

Dutch queen Wilhemina & princess Juliana as snowpeople in the Netherlands (1913) (via Nationaal Archief)

Humans are innately drawn to creating effigies of their own likenesses, often forging the figures from a crude stack of frozen balls plopped one atop of another. Building a snowman utilizes materials that are free of cost, easy to manipulate, and plentiful in certain times and places. It requires minimal artistic skill, as the placement of a few simple twigs and rocks can furnish your creation with an eerily expressive personality.

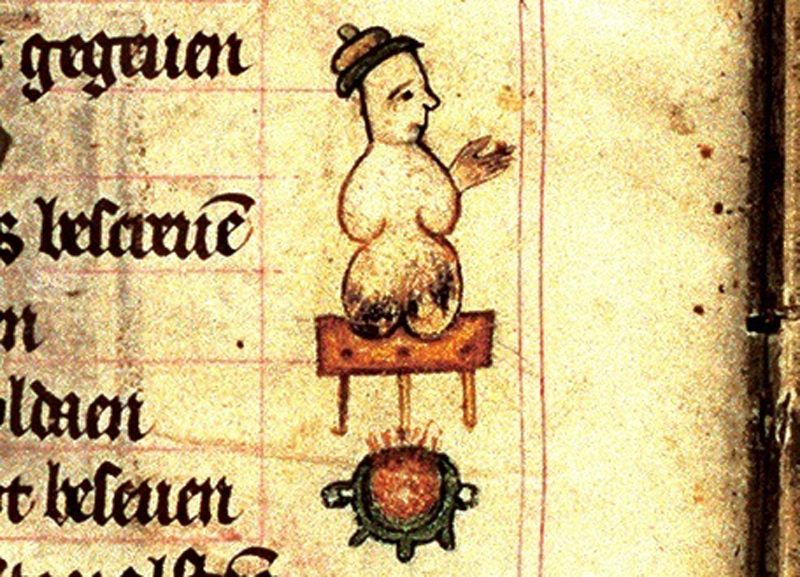

Snowman with charred backside in a 14th-century Book of Hours (via Koninklijke Bibliotheek)

Early snowman documentation has been discovered as far back as the Middle Ages, but we must assume that humans, creative beings that they are, have taken advantage of the icy materials that fall from the sky ever since winter and mankind have mutually existed. Bob Eckstein, author of The History of the Snowman, found the snowman’s earliest known depiction in an illuminated manuscript of the Book of Hours from 1380 in the Koninkijke Bibliotheek in The Hague, Netherlands (shown above).

The despondent snowman seems to be of anti-Semitic nature, shaped with the stacked-ball method, and donning a jaunty Jewish cap. As he sits slumped with his back turned to the deadly fire, the adjacent text pronounces the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. Apparently, plague-ridden Europeans needed a comical stooge onto whom they could foist their blame and frustration, and the Jewish snowman fit that bill.

Women attacking a cop snowman in a 1937 painting by Hans Dahl (via Wikimedia)

In the Middle Ages, building snowmen was a way for a community to find the silver lining in a horribly oppressive winter rife with starvation, poverty, and other life-threatening conditions. In 1511, the townspeople of Brussels banded together to construct over 100 snowmen in a public art installation known as the Miracle of 1511. This event was uncovered by Eckstein in his The History of the Snowman book.

Their snowmen embodied a dissatisfaction with the political climate, not to mention the six weeks of below-freezing weather. The Belgians rendered their anxieties into tangible, life-like models: a defecating demon, a humiliated king, and womenfolk getting buggered six ways to Sunday. Besides your typical sexually graphic and politically riled caricatures, the Belgian snowmen, Eckstein discovered, were often parodies of folklore figures, such as mermaids, unicorns, and village idiots.

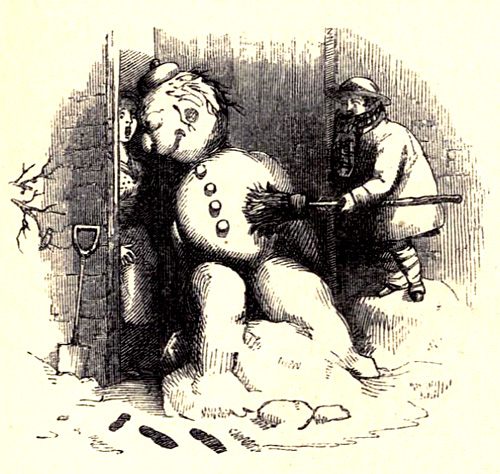

The Snowman Trick (1950), illustration by Luke Limner, Esq. (via Abaculi)

The snowman’s place in the traditional Christmas canon of jolly holiday diversions — along with ice-skating and horse-drawn sleighs — gained a higher status in the early Victorian era, when Prince Albert thrust his penchant for German holiday fun onto England. Santa Claus and the snowman became ubiquitous icons who soared hand-in-hand o’er the land of commodified Christmas kitsch.

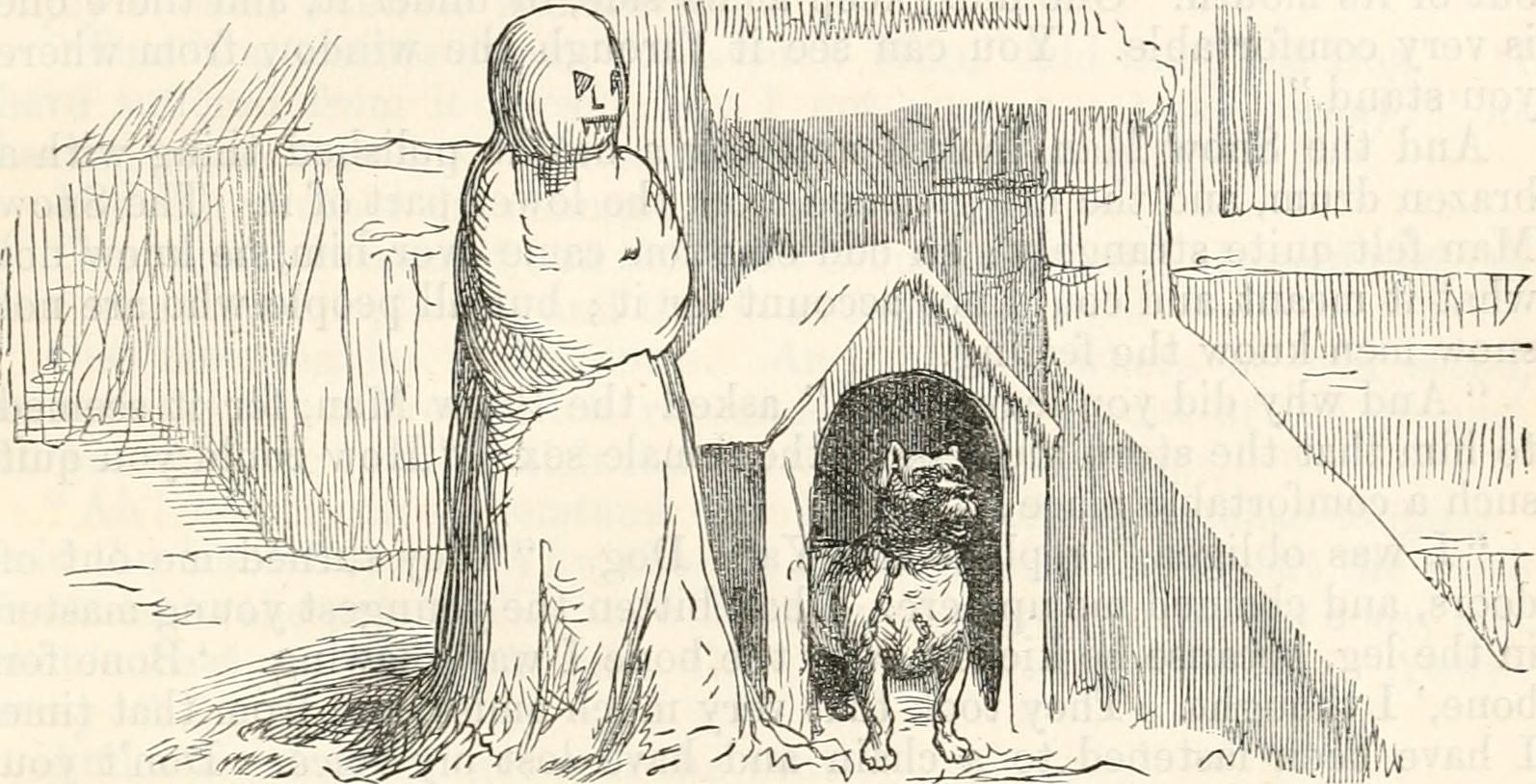

A snowman receives romantic advice from dog in Hans Christian Andersen’s “Stories for the Household” (1880s) (via Internet Archive Book Images)

The snowman’s lot in life is complicated — he is immobile, explicitly impermanent, and confined to an existence of ruminating upon his fate. He is the perfect metaphorical example of the human condition: longing for that which we cannot obtain, in his case touch and warmth. It’s believed that Hans Christian Andersen’s 1861 fairy tale, “The Snowman,” wherein a snowman falls unrequitedly in love with a stove, held symbolic implications of Andersen’s infatuation with Harald Scharff, a young ballet dancer at Copenhagen’s Royal Theatre. Andersen wrote about how the thing we love most can eventually destroy us, yet we happily sacrifice ourselves. When the “stove-sick” snowman gazes upon the burning oven from outside, he cries:

It is my only wish, my biggest wish; it would almost be unfair if it wasn’t granted. I must get in and lean against her, even if I have to break a window.

Modern-day authors, filmmakers, and artists of every ilk have appropriated the Frosty-type character as their own. The snowman has made appearances in hundreds of books and magazines, dozens of films, and seems to materialize at every critical time and place in history, just as long as Old Man Winter, Jack Frost, or any other personification of winter blows his snowy breath onto the land. The snowman’s persona is safe and placid, politically nonpartisan, unaffiliated with religion, and practically androgynous. Today’s snowman is fashioned with much less political allegory in favor of cheap, empty, irony, as he was commissioned to sell products such as liquor, laxatives, and rap albums.

Not unlike how the blank, smiling expression of a clown is inevitably considered creepy, the snowman has a wicked layer beneath his pure face. A snowman has portrayed the evil villain in slasher films and sci-fi TV shows, and depicted sexual humiliation in comic strips, kitschy products, and your own neighbor’s front yard. Today’s snowman is as easily a malicious serial killer as he is a fluffy children’s plaything. This marks the period Bob Eckstein refers to as the snowman’s White Trash Years (1975-2000).

Field of Japanese snowmen in Sapporo (photograph by Angelina Earley)

You can wait for a blizzard and construct your own demonic fornicating snowperson, or head out to one of the hundreds of snowman festivals and contests. For over 30 years the Japanese city of Sapporo, in the Hokkaido region, has hosted the Sapporo Snow Festival where an infestation of 12,000 mini snowmen cluster in a field, wearing cryptic messages from their makers.

The stalwart “Jacob” (photograph by Schubbay)

The stalwart “Jacob” (photograph by Schubbay)

There’s also the Bischofsgrün Snowman Festival (Schneemannfest), held every February in Bavaria, featuring “Jacob,” Germany’s über gigantic snowman.

Olympia, in Bethel, Maine (photograph by ChrisDag)

But the prize for the world’s biggest anthropomorphized snow pile goes to a snowlady named Olympia, created in 2008 by the townsfolk of Bethel, Maine, and named for the state senator Olympia Snowe. Built in a month-long plow fest, the 122-foot-tall conical she-beast was decked in massive snowflake jewels and six-foot-long eyelashes.

The strange ritual of the Sonoma snowmen (photograph by Lynn Friedman)

Meanwhile in California, every December Sonoma Valley fires up the holiday season with the Lighting of the Snowman Festival. This is what Californians do with a decisively snowless region during winter: plug in hundreds of electrical snowmen who appear to be marching in military formation.

Symbolically, destroying a snowy effigy can mark the end of icy months and the tyranny of winter. In Zurich, Switzerland, for example, a giant snowman called the Böögg is plugged with firecrackers and detonated to the delight of the cheering crowd.

At the Rose Sunday Festival in Weinheim-an-der-Bergstrasse, Germany, the mayor leads a parade through town, beseeching the local children to behave obediently in order to earn the privilege of spring. The children agree, naturally, and the townspeople incinerate a straw snowman. Lake Superior State University commandeered this tradition in the 1970s with their own Snowman Burning Day. Over the years, LSSU’s annual 12-foot-tall snowperson has represented slightly more political and social issues, whatever they feel needs symbolic burning, from sexism and cloning to the Ayatollah Khomeini and a rival hockey team.

Explosion of the Böög in Switzerland (photograph by Roland zh/Wikimedia)

Explosion of the Böög in Switzerland (photograph by Roland zh/Wikimedia)

Children and adults alike can therapeutically release their anger onto the snowman — really let him have it — without much consequence. Pelt him with snowballs, stab him, and run him over with your car. He won’t resent you! He’s harmless! That is, unless you consider it harmful to endure listening to Perry Como’s 1953 rendition of the hit tune, “Frosty the Snowman.”

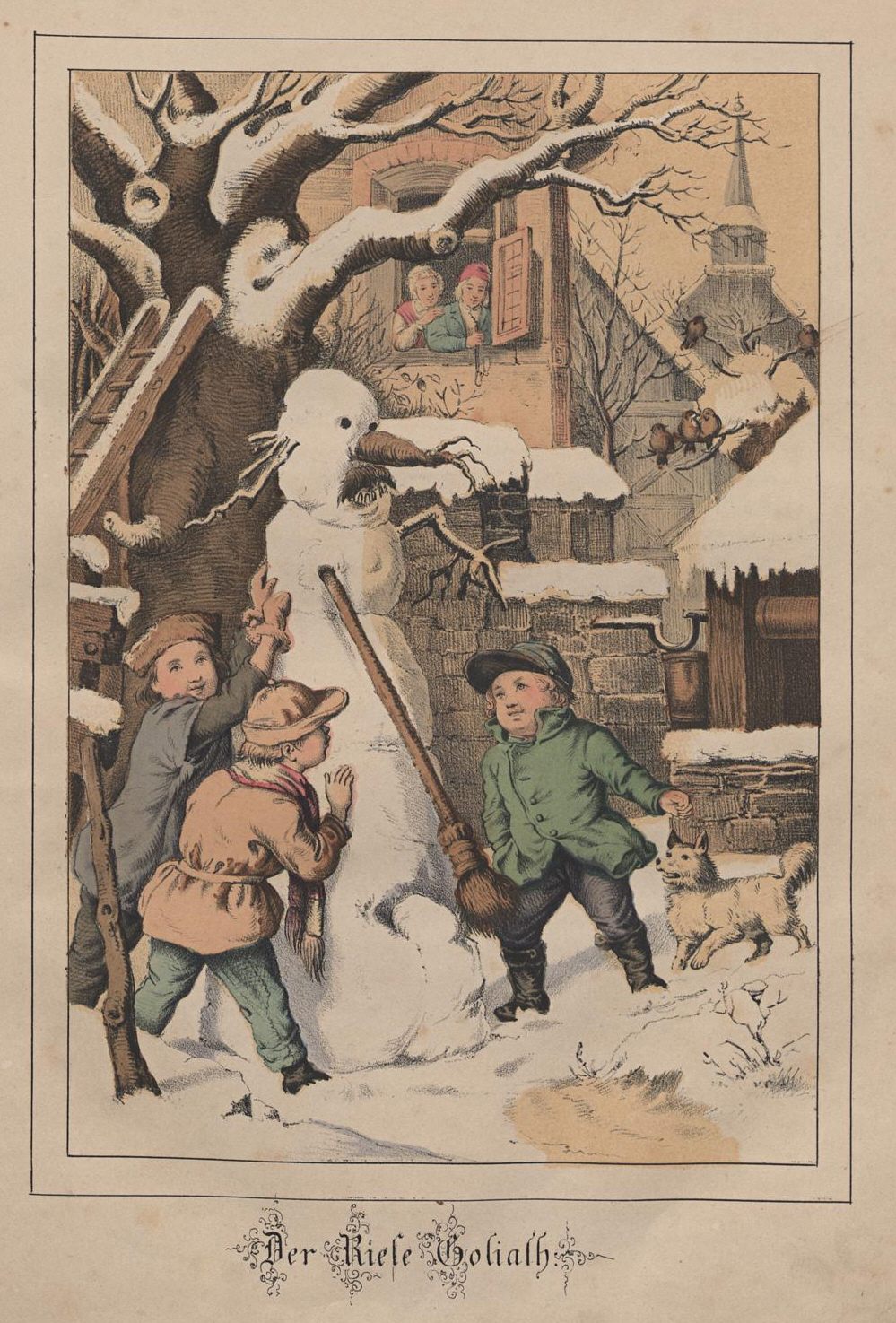

“The Giant Goliath” snowman illustrated by Franz Wiedemann (1860) (via Wikimedia)

“The Giant Goliath” snowman illustrated by Franz Wiedemann (1860) (via Wikimedia)

For more on this curious winter tradition, we recommend Bob Eckstein’s The History of the Snowman.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook