A Unifying Yiddish Library in Tel Aviv’s Dilapidated Bus Station

Amid sputtering engines and towering stacks of books, people gather to revive a suppressed language.

It happened one night in 2006. The actor and singer Mendy Cahan, accompanied by two bitter and exhausted movers, parked a large van with a container in the parking lot of Tel Aviv’s New Central Bus Station. Cahan quietly opened the container, and the trio began to pull out large boxes sealed with duct tape. Shortly after, they had carried the boxes to the station’s fifth floor.

Construction of the Central Bus Station, which was supposed to be the world’s biggest shopping mall, began in 1967, but the plans for developing it as a shopping center collapsed. The station opened in 1993, in a grand, fanciful ceremony attended by Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. Its architects promised a five-star-level shopping and transportation center, but its levels, corridors and wings confused shoppers, so they stopped coming. Levels 1 and 2, which included stores, bus stations and a passenger hall, were found to suffer from severe air pollution shortly after the opening, and were closed off. Now, some areas teem with life, while others are almost abandoned. Levels 4 (the street level), 6, and 7 are currently active. The fifth floor has come to be known as “The Artists’ Compound.” When businesses began abandoning the station in the mid-1990s, the city of Tel Aviv decided to offer spaces as cheap studios for artists. Most of those artists have since departed.

Cahan opened the door to a former studio on the fifth floor, revealing a large, empty space. Over the course of more than 24 hours, he filled this space with boxes containing more than four tons of books in Yiddish. Thirteen years after the original Yung Yidish library opened in Jerusalem, the Tel Aviv branch was born. Its non-circulating collection is perhaps the largest array of Yiddish books and newspapers in Israel, yet the institution survives on a lean diet of donations.

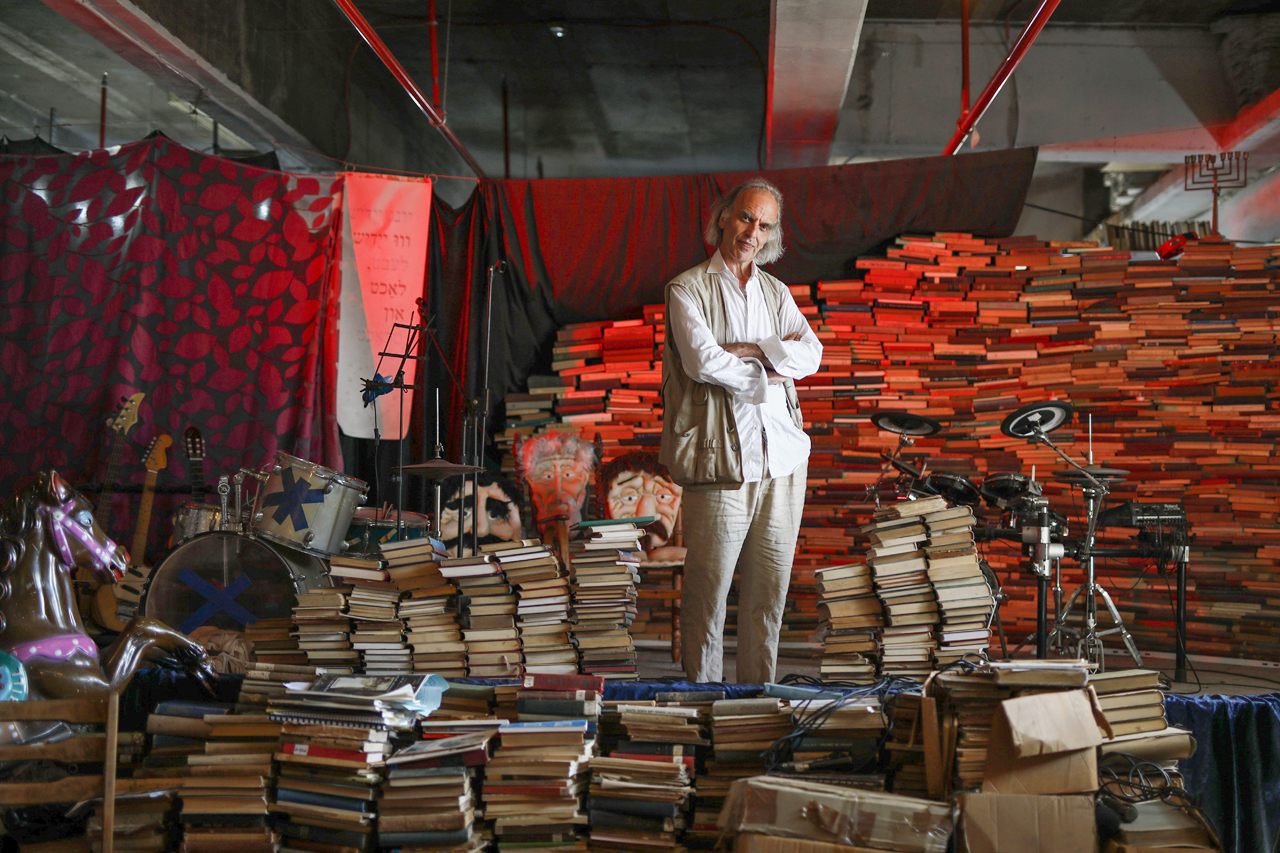

When he opens the door today, more than a decade after that night, Cahan is surrounded by a wide, low-ceilinged space containing tens of thousands of books. Between the mounds of books there is a mish-mash of sofas and couches. Yiddish works from the late 19th century bloom between late 20th-century concrete walls and air vents. A bus departs from the floor above once every 30 seconds, and its roar sends a vibration through the ceiling and the Yiddish books. Below the library, on the fourth and third floors, there are stalls selling clothing, food, and porn, alongside synagogues and churches. A wide hallway overlooking the third floor is called Manila Street, and holds shops operated by Filipino migrant workers.

We sit around a low coffee table at Yung Yidish that holds a bottle of Slivovitz brandy. Next to us there is a messy pile of cardboard boxes holding 4,000 books and newspapers in Yiddish. “The Yiddish library owners are dying,” says Cahan. “These boxes came from a huge Yiddish library in central Tel Aviv which is about to be closed down. They asked us to save what we can.”

Cahan was born into a Modern Orthodox family in Antwerp. “The first language at home was Yiddish, but French and English were also spoken, and the book cases held religious books next to books by Camus and Sartre,” he says. His parents were born in Romania. During the Holocaust, his father was sent to concentration and labor camps. “He was an attractive man,” says Cahan, “and in one of the labor camps a young Christian woman approached him and offered that he live with her. She left him a key to a hiding place. My father held on to the key that entire night, tormented by guilt. God, the Torah and the Mitzvahs were a living thing to him. After a sleepless night, he threw the key away.”

Before World War II, there were about 11 million Yiddish speakers worldwide, approximately 60 percent of the global Jewish population. The murder of millions of Yiddish speakers in the Holocaust and the suppression of Yiddish speakers by Stalin have almost obliterated it. “Yiddish during the Holocaust underwent a transformation,” explains Cahan. Its vocabulary was reduced because everyone was “living in constant terror, fighting to survive.” “We know about this change because inside this hell there were anthropologists and philologists who kept working, kept paying attention.”

Cahan decided to leave religion in his early 20s. During that time, he immigrated to Israel “because of the sun” and studied philosophy. Shortly after arriving in Israel, Cahan began collecting Yiddish books at home. The number of books grew, and the collection moved between spaces. In 2006, he squatted on the current space. The landlord, Nitsba Group, soon became aware of his presence and began charging rent and municipal taxes. Cahan wanted his space to be recognized as a private museum, which would allow him to pay the discounted tax rate awarded to nonprofits. When he refused to pay the full business rate, municipal inspectors seized his rare Yiddish typewriter, produced in 1910. He still hasn’t gotten it back, though he did eventually pay his taxes in full. During these times of struggle, now long over, there were also other challenges: flooding, leaks, some birds that nested between the piles of books, a cat who had kittens here.

Today, the library of the Yung Yidish non-profit includes about 60,000 titles, brought here from the inheritances and libraries of private individuals from Lithuania, Russia, and Argentina. It offers poetry readings and music shows, hosts festivals and Yiddish courses, and collects and preserves Yiddish magazines, records, and letters. And all this, while consisting on a lean diet of donations.

The quest to revive Yiddish, not just preserve it, is not a simple one. The estimated number of current Yiddish speakers varies according to the source. Rutgers University’s Department of Jewish Studies estimates 600,000. According to the National Authority for Yiddish Culture, there are currently two million Yiddish speakers worldwide, including a few hundred thousand in Israel (the ultra-orthodox in Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, and Bnei Brak) and a similar number in the United States (mainly New York).

In the case of Israel, the challenge is even more complex. The Zionists who built the country viewed Yiddish as a threat to the revival of Hebrew and took steps to suppress it, sometimes aggressively. My father’s and mother’s parents, whose native tongue was Yiddish, never taught the language to my parents. Like me, most of the secular Ashkenazi Jews in Israel don’t speak Yiddish.

Cahan views Israel’s Zionist founders as an “exotic bunch”. But he understands the steps taken by the revivers of Hebrew. “In that point in history, your grandmother had the choice between 600 wonderful children’s books in Yiddish, and three children’s books in Hebrew,” he says. “If she had exposed your mother to the rich variety in Yiddish, your mother would never have chosen Hebrew.”

Spoken Hasidic Yiddish is almost unexplored in the academic world. “We treat spoken Yiddish as marginal, but a language spoken by half a million to [a] million people is not marginal,” says Dr. Kriszta Eszter Szendroi, an Associate Professor of Linguistics at University College London and a leader of a major research project studying contemporary spoken Yiddish in the Hasidic communities worldwide.

Szendroi, a native of Hungary who has been living in London for the past 20 years, began studying Hasidic Yiddish about three years ago. Cahan was one of her teachers, and they have built a friendship.

“As soon as I walked into Yung Yidish, I felt at home,” Szendroi says. “As a Jew on my father’s side and a Christian on my mother’s, integrating into contemporary Europe wasn’t easy for me, and in Yung Yidish I feel at home because it’s a place without black and white. In today’s world, it is important that such places exist.”

On my way to Yung Yidish I walk through a maze of recesses in the bus station, some that are hidden as the one used by Cahan. In a nearby corridor, a group of Filipino migrant children rehearses a street dance. Last year they performed in a festival hosted by Yung Yidish that included artwork, fanzines, performances, music, and poetry readings. Over the years, Yung Yidish has served as a Good Samaritan for many of its neighbors, in many small, everyday ways.

While I’m at the library, Ramon Mendesona, the owner of a nearby ceramics studio, enters the place. “My work is very repetitive,” he says. “I work 12 hours a day and come into Yung Yidish in the evening to have a cigarette and drink wine, talk, break the routine.” He immigrated to Israel from the USSR in 1991, “before the revolution, before the empty shops and the chaos.” When he first visited Yung Yidish, he decided to study Yiddish here, in order to understand the language spoken at home. Mendesona’s experience is different than that of Cahan’s father. “The image of the USSR is that everything was forbidden there, but it’s not true,” he says. “The older generations in my family spoke Yiddish without fear of suppression, and it died because people left religion and opened up the world and it was no longer needed in daily life.”

Night falls. I ask Cahan if he ever felt like staying here overnight. “It’s tempting, but also uncomfortable,” he says. “There are thousands of voices here. I’ll have a hard time sleeping here.” He finishes the last shot of Slivovitz, picks up his motorcycle helmet and walks to his bike out in the parking lot, where it all began.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook