140 Years Ago, Captain Matthew Webb Swam The English Channel And Made Swimming Cool

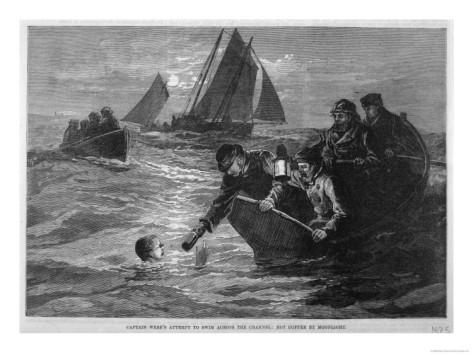

An artist’s rendering of Captain Webb accepting libations during the long swim. (Image: CS&PF/Public Domain)

An artist’s rendering of Captain Webb accepting libations during the long swim. (Image: CS&PF/Public Domain)

It’s a hot August day, and you, like many, may choose to beat the heat with a few bracing laps in your local water feature. If you show up at the pool or pond to find the lanes crowded and the shallows swamped, you have only one man to blame—Captain Matthew Webb.

The 19th-century swimming sensation loved water so much it eventually killed him. But first, 140 years ago today, he swam the English Channel, catapulting himself into fame and his favorite sport into respectability.

Webb was born in January of 1848, in Shropshire, England. When he was six years old, his parents moved their growing family to Coalbrooksdale, a mining town nestled in the the valley of the River Severn, the longest in the UK. Young Webb spent his days testing himself against the river, swimming across one way and crossing back via the precarious Buildwas Rail Bridge, watching the water rush beneath the struts. Stuck inside during the long British winters, he slaked his thirst for adventure by reading seafaring tales—like W.H.G. Kingston’s Old Jack, in which the titular sailor tells of “Naval Exploits,” “Pirate Strongholds,” and swimmers so good they fight off sea monsters with their bare hands.

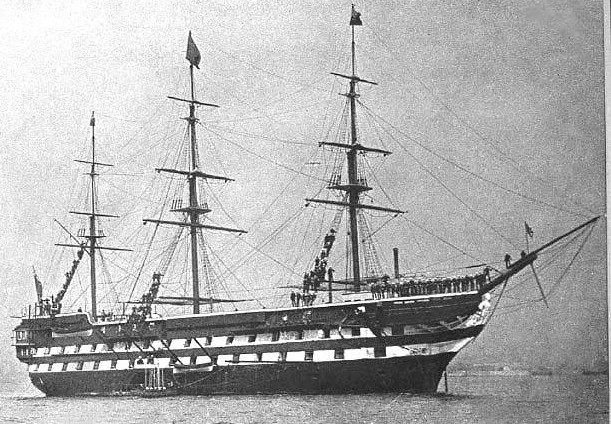

By age 12, Webb had enlisted as a merchant seaman and was aboard the HMS Conway, a naval training ship. He then spent the next decade-and-a-half hopping between cargo ships, trading vessels, and passenger cruisers, and served a brief stint as captain of the steamship Emerald, where he had trouble holding onto his crew due to what The History Channel calls his “well-deserved reputation for recklessness.”

The HMS Conway, swarming with reckless boys. (Photo: Flapdragon/WikiCommons Public Domain)

He also had a tendency to jump overboard and rescue people whenever he had a chance—a habit he picked up after saving a fellow classmate who fell off the Conway, and honed while home on break by pulling his younger brother out of the river. One particularly daring but unsuccessful rescue attempt garnered him the first ever Stanhope Gold Medal for gallantry, still the Royal Humane Society’s most prestigious award.

As evidenced by this hobby, Webb didn’t really want to be on the water: he wanted to be in it. In the 19th century, there weren’t very many opportunities for aspiring professional swimmers—the Plague Years had kept germ-fearing Europeans out of the water, and the sport had a few centuries of suspicion to make up for. Rather than racing other pros or teaching amateurs, Webb slowly made his hobby more lucrative by marketing himself as an attraction. He invented showy scenarios and rose to self-imposed challenges, some serious and some silly, and he always took home a purse when others bet against him—in the same year, he wagered that he could swim 20 miles from Blackwell Pier to Gravesend faster than anyone had before, and also that he could stay in the water “longer than a Newfoundland dog.” He beat the record in four hours and 45 minutes, and the dog in about an hour and a half.

An illustration of Webb, decked out in medals. (Image: Illustrated London News/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

After dabbling in this for a couple of years, Webb was on the lookout for a massive stunt, the kind that could transform him from a well-decorated journeyman into an international superstar. It fell into his lap thanks to one of his equally fanatical peers. J.B. Johnson tried to swim the English Channel unaided in 1872, for unrecorded reasons—likely just because it was there. Little is known about Johnson except that he failed, and was pulled out of the water after about an hour. Webb knew he could do better, and, his goal set, Webb quit his captaincy in 1873 and threw himself into the sea full-time.

He trained in the Lambeth baths, and then the Thames, swimming miles every day. He paid equal attention to the showman’s end of things, and hired a coach, Fred Beckwith, a “professor of swimming” better known for orchestrating stunts and managing bets than for his actual skills in the water. Together they spread his name and intentions all over town: a poem by Sir John Betjeman, written after Webb’s death, describes his ghost “swimming along the old canal/ That carried the bricks to Lawley” and arriving “dripping along in a bathing dress/ To the Saturday evening meeting,” which seems, if not completely factually accurate, close to the truth in spirit.

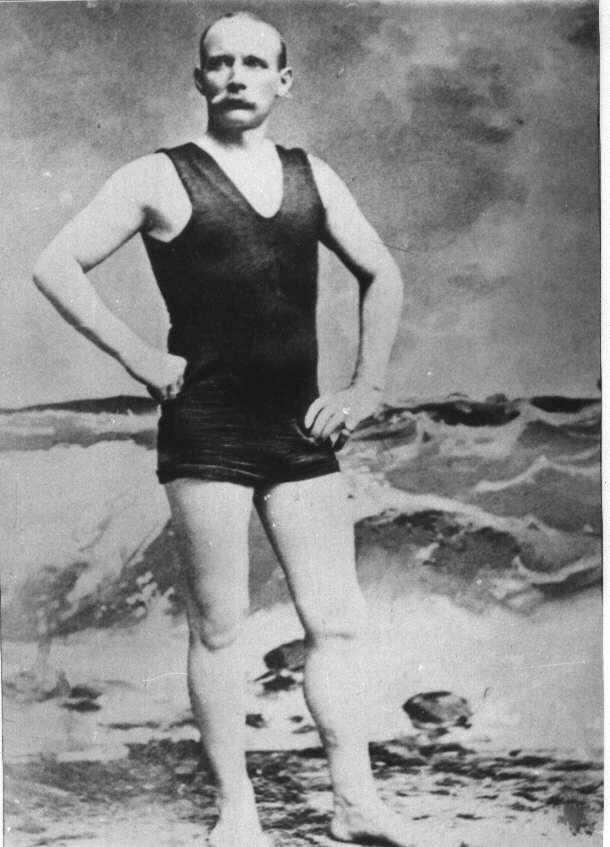

A portrait of Webb in his element. (Photo: CS&PF/Public Domain)

In April of 1875, American showman Paul “The Fearless Frogman” Boyton hurried things along by successfully crossing the Channel wearing an inflatable rubber “immersion suit.” Powered by a small canvas sail and fueled by scrambled eggs and brandy, Boyton’s crossing wasn’t nearly as physically impressive as an unaided one would be—but he did capture a lot of headlines, and Webb’s ire. A few months later, Webb was prepared to take the plunge.

His first attempt, on August 12th, was derailed by strong currents and bad weather. Twelve days later, on the 24th, he was ready to try again. He covered himself in porpoise oil, put on his red silk swimsuit, and leapt off Dover Pier around 1 pm. His new coach, Arthur Payne, had written the press announcing his athlete’s intentions (along with a “paltry bet of 20 pounds to one,” which he invited interested parties to match), and the 3 boats that trailed Webb as he made his way into the Channel carried Payne, a small support staff, a few journalists, and an illustrator.

Webb swam steadily through the afternoon and into the evening. Other than some stops for coffee and beef tea from his support team, and the occasional run-in with a porpoise or jellyfish, he stopped hardly at all. Like most Europeans at the time, Webb swam breaststroke—freestyle, though faster, was considered ”violent and grotesque”—and those who watched him described a large, mustached man stroking high in the water, with “slow and steady arm strokes,” the soles of his feet emerging after each kick. Payne occasionally jumped in to join him.

When the sun set, the water was illuminated by a three-quarter moon from above and phosphorescence from below, and when it rose again, the sea was “calm as glass.” That morning, Webb flagged for a little bit in the currents close to shore, but a nearby mailboat sang “Rule Britannia” for him, and by 10:41 a.m. he was through them, and stumbling onto the beach at Calais. “I felt a gulping sensation in my throat as the old tune, which I had heard in all parts of the world, once more struck my ears under circumstances so extra-ordinary,” he later wrote in his diary. “I felt now I should do it, and I did it.”

The Strait of Dover today. (Photo: NASA/Public Domain)

He was slightly delirious, and the sailors who helped him stagger up the beach said he felt like a “lump of cold tallow.” They put him in a carriage and sent him to the Paris Hotel to sleep. He had been swimming for 21 hours and 45 minutes.

He was famous virtually by the time he woke up—“the successful accomplishment of such a feat gave Webb a pre-eminence among all swimmers of whom there is any record,” biographers wrote decades later. The London Stock Exchange set up a fund for him and raised 2,424 pounds, just over $300,000 in modern dollars. His hometown threw such a big parade for him that, legend has it, a pig propped himself up against a wall to watch the procession, leaning on his front trotters and wondering what all the fuss was about. Swimming also surged into the public consciousness. Just as Webb had wanted to grow up to be Old Jack, every kid wanted to be Captain Webb. The British government began building municipal pools to keep up with the demand.

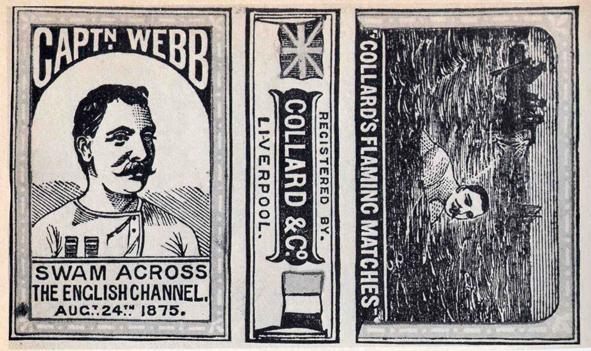

A box of Captn Webb matches. (Image: CS&PF/Public Domain)

Webb capitalized on his fame, traveling overseas to give lecture tours and elongating his string of stunts. He swam from Sandy Hook to Manhattan Beach in 8 hours. He beat Fearless Frogman Boyton in a race off Nantasket Beach, and once “won a thousand pounds for floating in a tank of water at a Boston Horticultural Show for 128 hours.” He drew crowds rain or shine, and his face graced matchboxes all over Britain. Everyone wanted to see the mustached man who could swim forever, even if it was just while they were lighting a cigarette.

But the crossing was the peak of his fame—no tank exhibition or Stateside grudge match could top it. In July 1883, nearly eight years after he first dived into the Channel, Webb tried to outdo himself. Seeking, in the words of his friend Robert Watson, “money and imperishable fame,” he set up an exhibition swim through the rapids beneath Niagara Falls, an incredibly dangerous gauntlet of rock-filled whirlpools that had already killed a number of hapless people. Though spectators, as always, poured out to watch, the train and hotel companies refused to cut a deal with Webb, wanting nothing to do with what they saw as a suicide mission.

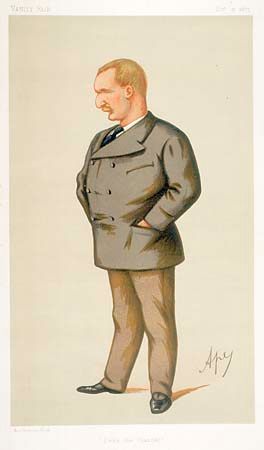

This caricature of Webb, by Carlo Pelligrini ran in Vanity Fair after he swam the Channel. Legend has it the character of Inspector Clouseau was based on Webb. (Image: WikiCommons/Public Domain)

Webb was piloted into the middle of the rapids, and leapt from the prow of the boat in the same red silk costume he had worn to swim the Channel. Within 10 minutes he was sucked under, and his body was found four days later, his swimsuit ”torn to shreds.” He was 35.

To this day, some hold that Webb was secretly broke, sick, and unhappy, and that he had meant to either turn things around that day or go down trying. Others are sure he thought he could do it, just as he had done everything else. Fred Kyle, Webb’s business manager, told the New York Times that Webb “had everything to live for.” When anyone advised him about the rapids’ dangers, Kyle said, “he would invariably say good-naturedly,” ‘he thinks he knows a lot about the water, doesn’t he?’” Webb was fearless, and occasionally reckless, but he sure knew a lot about the water. And thanks to him, now the rest of us do, too.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook