The 19th-Century Woman’s Secret Guide to Birth Control

Shared books, homemade concoctions, and a whisper network thwarted Gilded Age efforts to limit women’s access to health care.

In 1878, Sarah Chase was on the lecture circuit. A graduate of a homeopathic college and a single mother, Chase made her living in Manhattan giving talks at community spaces around the city and, afterwards, selling what contemporary police reports and newspapers called “vile articles,” including sponges, syringes, and instructions for how to, in the parlance of the era, “bring down the menses,” in other words, induce an abortion.

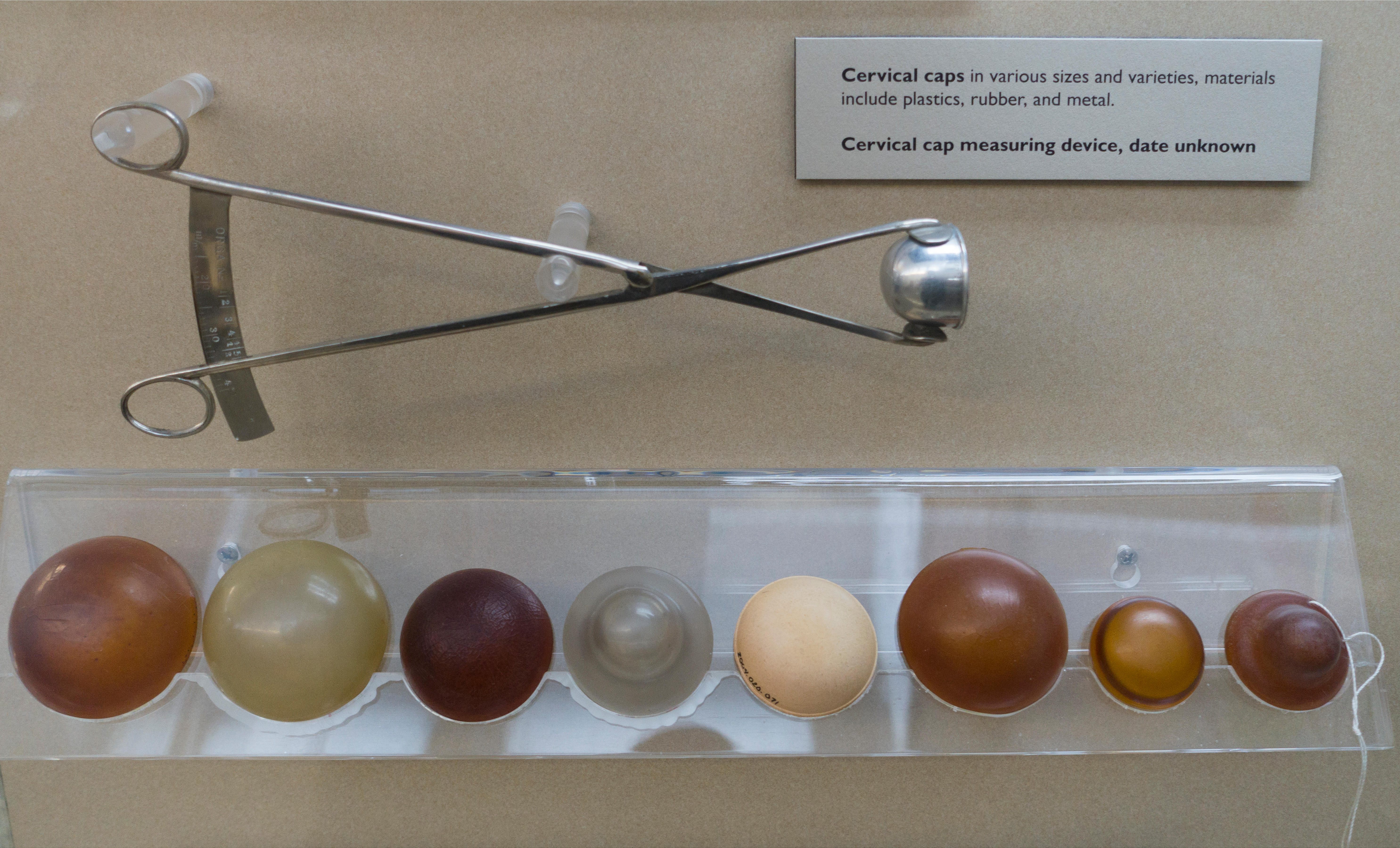

Examples of the kind of ad hoc birth control devices that Chase sold are now on display at the Dittrick Museum of Medical History at Case Western Reserve University, where visitors can peruse objects and exhibits covering ancient times to the present that demonstrate that women have always shared information about how to control their reproductive health—and others have always tried to stop them.

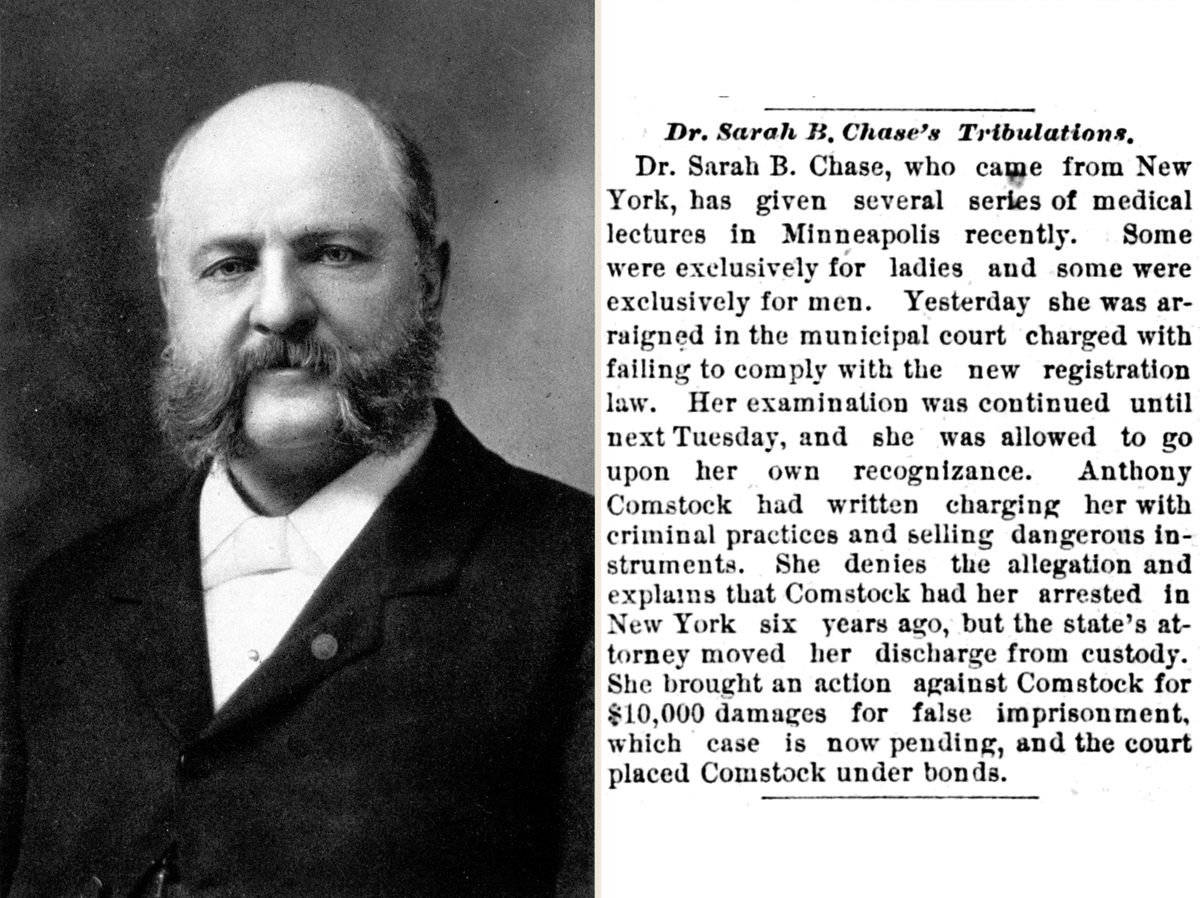

In the 19th century, Chase’s livelihood raised the hackles of one of the most infamous anti-birth control crusaders of modern times: Anthony Comstock, the lobbyist behind the eponymous laws that criminalized selling birth control in 1873. In an episode chronicled by Andrea Tone in Devices and Desires: A History of Contraceptives in America, Comstock set up a sting operation to catch Chase in the act and promptly served her an arrest warrant.

This was the wild west era of birth control and abortion, the period after Comstock’s laws went into effect in 1873 and before Margaret Sanger’s clinics in the 1910s. A cursory, top-down look at history suggests that in this period, birth control was illegal, abortion was unheard of, and women were at the mercy of biology when it came to controlling their reproductive fates. Indeed, in 2017, a journalist stated on NPR that abortion was not a part of American life in the 19th century because the word “abortion” appeared in no newspapers from that time (an assertion that was later corrected thanks to an outcry from historians).

But to understand the way abortion and birth control were disseminated during this period is to understand how information passes outside of official channels. Birth control was a rip-roaring trade in Gilded Age America, at least for some white, working- and middle-class, literate women. Plucky entrepreneurs—some of them women like Sarah Chase—manufactured birth control and abortifacients (which were not always safe or effective), dodging authorities and courting prison time, while information about obtaining and using these items passed readily between women through coded language and whisper networks.

Whisper networks, said Naomi Rendina, who has a PhD in history from Case Western Reserve University, have long facilitated conversations between women about their bodies and their fertility. “Women sharing information between each other has been going on for hundreds of years,” she said.

In the age of Comstock, writes Andrea Tone, a network of “local and informal” instruction developed to pass information about birth control: how to use it and who was selling it. This informational network drew on a long history of female whisper networks in America, dating back to the Puritans and their midwives.

“If you went into the local drugstore, you might be embarrassed to pick out the pessary you wanted,” said Lauren Thompson, one of the historians who corrected the NPR reporter on Twitter. “It was stigmatized, even as people continued to talk about those things at the kitchen table, share ideas over coffee. It was still a whisper thing.”

This whisper network was so powerful, writes Tone, “that once birth control became legal, contraceptive manufacturers endeavored to discredit it through advertising campaigns designed to bolster consumer support of products that were ‘scientifically tested’ instead of ‘just’ recommended by friends.”

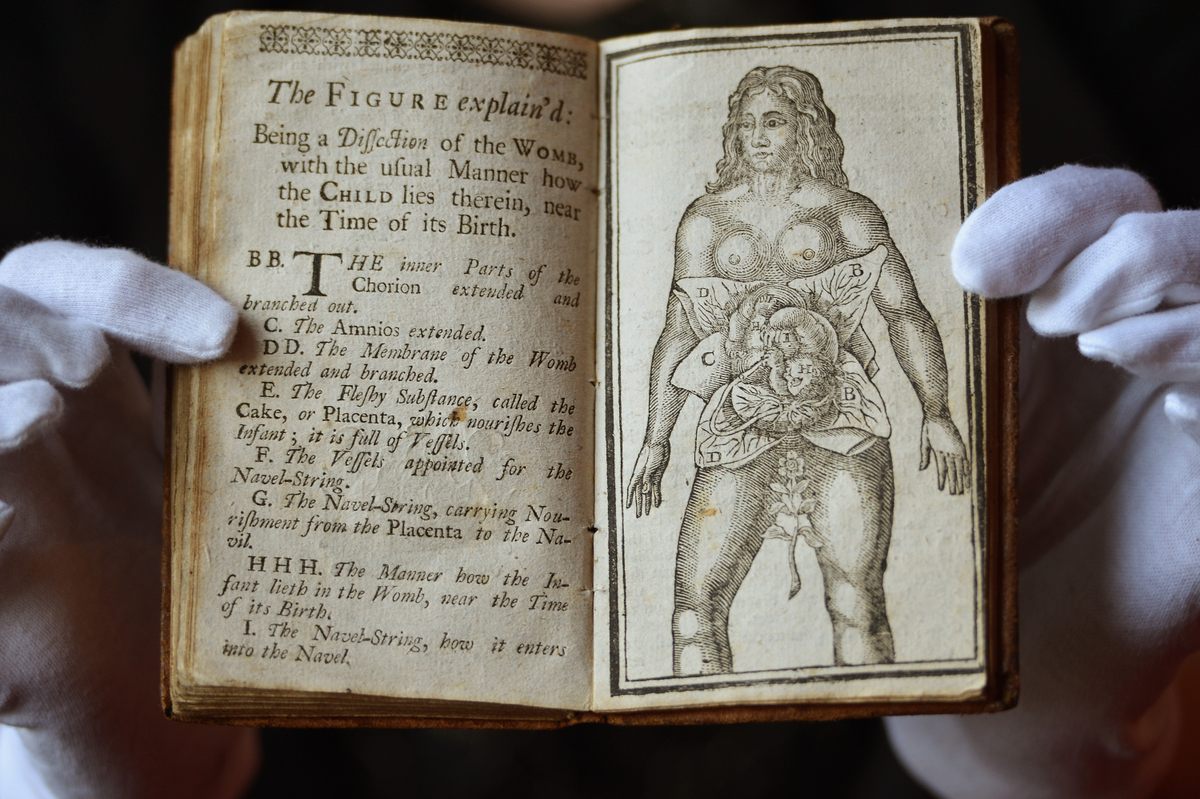

Donna Drucker, author of Contraception: A Concise History, notes that books also played an important role in spreading information about reproductive health. This written material, she said, included handbooks like the 17th century classic Aristotle’s Masterpiece (falsely attributed to the philosopher) and pamphlets like Fruits of Philosophy, written by an 1832 Massachusetts physician who recommended inserting a sponge with an attached ribbon into the vagina before sex. These pamphlets were precursors to the written materials distributed by later birth control reformers, like Margaret Sanger’s What Every Girl Should Know.

Sponges, condoms, douches—all these contemporary methods existed in more primitive forms in the 19th century. The Dittrick Museum includes a selection of more than 1,100 of these historical birth control items, which started as a collection of 650 objects donated to the museum in 2004 by a pharmaceutical president: a graphite sketch of an enema or douche for a catalog, a yellow “sanitary sponge” packaged neatly in gauze, condoms made of animal membranes, metal “Dumas caps,” which were basically diaphragms (although these were all the rage in Europe, they were difficult to find in America at this time). Many went right for the back garden and made teas, using pennyroyal, tansy, and ergot.

Some of these methods, said Drucker, could be concocted and implemented at home (she emphasized that they should not be tried at home). But some had to be purchased. Although some companies like Colgate risked Comstockian ire by manufacturing contraceptives alongside their more legal products, overall, the vice laws made this the golden age of small-scale, black-market birth control, argues Tone. Besides Sarah Chase, Tone writes about one Harriet Losey of Kentucky who sold her contraceptives as “Madame Zelaski,” and Antoinette Hon, a Polish immigrant who sold a douching powder of boric acid, alum, and zinc sulfate under the moniker “Mrs. Hon.” Tone writes that the stigma already surrounding contraception granted some women the opportunity to become entrepreneurs at a time when other fields shut them out. Additionally, women’s existing knowledge of household cleaners and products helped them to concoct and market remedies based on these chemicals.

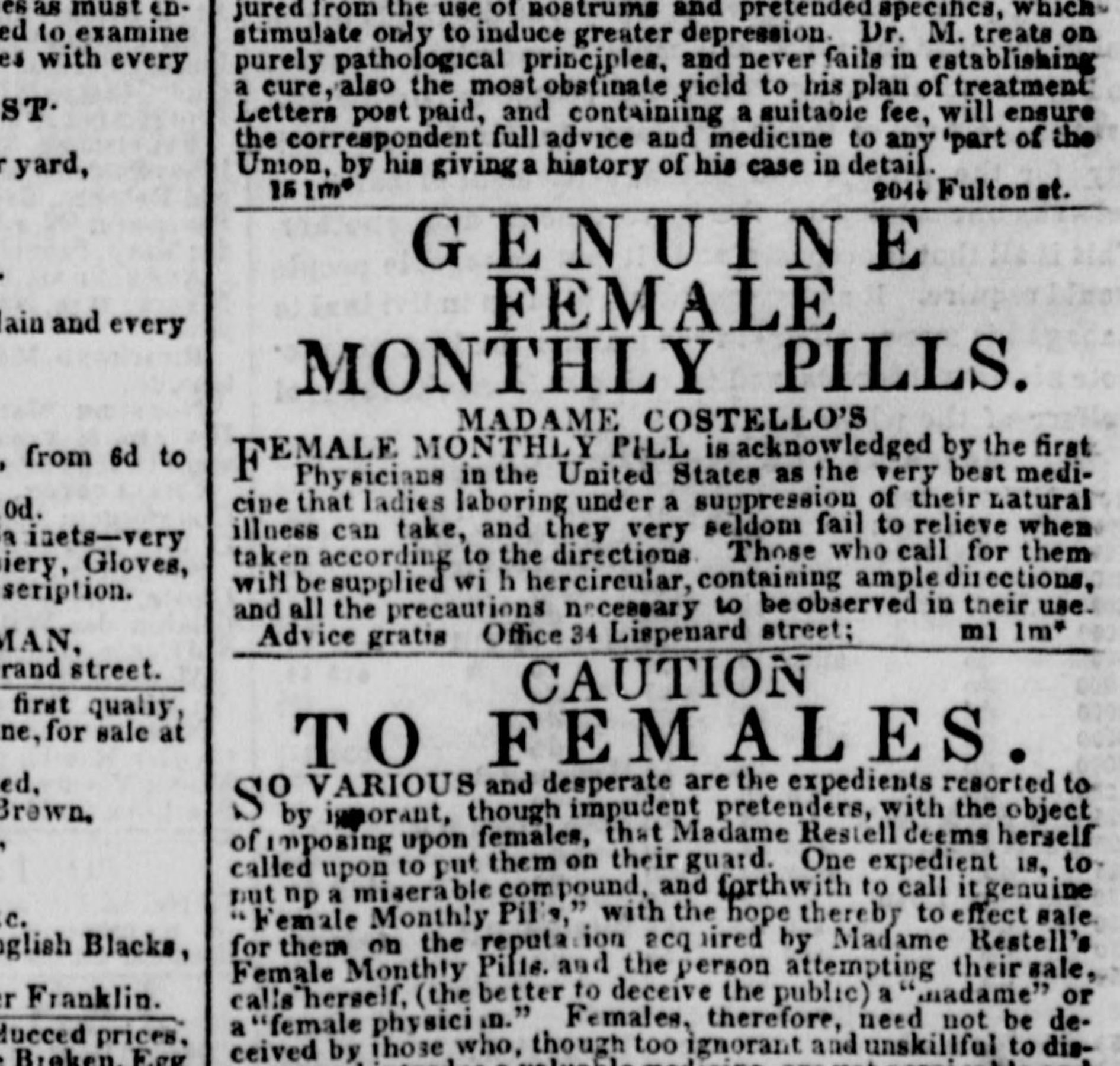

This isn’t to say that everybody had access to such products. An average middle class white high school graduate in, say, Chicago in 1885 might not have had the language or resources to ask a doctor for birth control or to seek out these devices herself, said Drucker (less is known about the southern and eastern European immigrants moving to America at this time, and practices among formerly enslaved women differed from their white counterparts). But people who had the knowledge and wherewithal to seek out birth control knew how to crack the code. That’s the second piece of the puzzle besides whisper networks: coded language designed to thwart the censors. Every day, across the nation, ads for abortion and birth control appeared in newspapers. Readers just had to know what to look for. “Women had to get creative” about how to get that information out, said Rendina. It was “restoring the menses,” not an abortion. It was “getting rid of a blockage,” or “cleansing the uterus. They came up with all these ridiculous euphemisms.”

A perusal of newspapers from this period shows advertisements for “Mother’s helper” or “Portuguese female pills,” medicine for those “laboring under the suppression of their natural illness,” “renovating pills from Germany” and the like.

Even the law didn’t always do what Comstock hoped in preventing the sale of these devices. Famed abortionist Madame Restell, whose advertisements promised “preventative powders” to “the married ladies,” committed suicide in 1878 following criminal charges under the Comstock laws. But Sarah Chase, the lecturer and birth control entrepreneur who fell prey to a Comstock sting operation, was never convicted. She was arrested five more times before the turn of the century and only served jail time once, because a patient died from an abortion.

As Tone writes, “a law did not necessarily work the fundamental change its proponents desired.” Comstock wanted to stop the dissemination of “obscene” materials and the sale of birth control. He failed, though it would take nearly a century before the birth control prohibitions in the Comstock laws were nullified.

“People never, ever, ever stopped using birth control or abortion,” said Thompson. “All the Comstock laws did was push that advice and information underground and codify the whisper network in a bad way, and I think we’re going to see a revival of that with these abortion bans, let alone the actual overturning of Roe. The key takeaway is pregnant people have always had abortions, have always used birth control. It’s not going to go away just because you make a law.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook