A Gas Pipeline Could Make Marfa’s Mystery Lights Disappear

They might be in danger after 130 years.

The Marfa Mystery Lights Brigade at its debut action. (Photo: Vicki Gibson)

Normally, part of the magic of Marfa’s mystery lights is that out on the flats, where the lights appear, there are no roads and no houses. Whatever the cause of the lights—and in 130 years, no one has ever been able to come up with a foolproof explanation—the lack of human activity has been a key part of the mystery of these red and white spots dancing on the horizon.

Right now, though, there is human movement out on the flats. Five miles to the southwest of the Marfa Lights Viewing Station, the low building erected at one of the most popular light-viewing spots, workers on the Trans Pecos pipeline are preparing to lay a 42-inch natural gas pipeline into the ground.

The Marfa lights in the distance. (Photo: Nicolas Henderson/CC BY 2.0)

“You can see the pipe from the viewing station with the naked eye,” says Alyce Santoro, a member of the grassroots group Defend Big Bend.

The pipeline will run straight through this region, until it reaches the border with Mexico. It’s intended to open new markets to Texas natural gas, but Santoro and other activists fear that it will take away the allure of this part of the state, where the population is sparse and open vistas of mountains and desert dominate the landscape.

One local filmed pipeline moving past her yard on usually unused tracks. (Video: Kendra)

Already, the pipeline construction is a threat to the Marfa Lights: if no one knows what causes them, how can they be protected?

“It’s the first tangible thing in this area that people will watch disappear,” says Santoro.

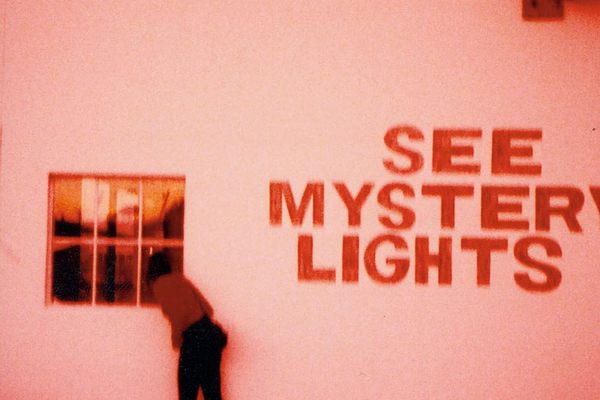

On Friday night, she and more than 30 others, the newly formed Marfa Mystery Lights Brigade, brought their own lights to the viewing station, with the intention of calling attention to the pipeline. They had 17 letters outlined in red LED lights, and when the bridge held them up, they read, “Save Mystery Lights.”

The plaque at the Marfa Lights Viewing Center. (Photo: Peter Ash Lee)

Texas is criss-crossed with pipelines: it has more natural gas pipeline miles than any other state, by far, and, according to Texas Monthly, about one-sixth of the country’s total pipeline miles. But Big Bend, where Texas’ western arm droops into Mexico along the route of the Rio Grande, has remained empty of oil and gas infrastructure, and, for the most part, people. Even the most popular attractions, Big Bend Ranch State Park and Big Bend National Park, which offer expansive vistas of otherworldly desert mountains along the border, attract sparse crowds. The national park gets between 300 and 400 thousand visitors a year—an order of magnitude less than the system’s most popular parks.

Locals are posting photos under #defendbigbend. (Photo: Joe Edd Waggoñer)

The route of the Trans Pecos pipeline cuts right through Big Bend, just past Marfa, to Presidio, a small border town just north of the state park. From there, another pipeline project will carry the gas further into Mexico’s interior. This natural gas could supplant more carbon-intensive coal-fired power, which has some environmental benefits. Increasingly, though, climate activists are fighting against any new fossil fuel infrastructure and arguing that energy investment should focus instead on renewable sources.

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission has already given the Trans Pecos project the initial go-ahead. But Energy Transfer Partners, the company behind the project, is still fighting with landowners along the pipeline’s path for access.

“This is the one place in the state that’s pipeline free. We want to keep it that way,” says David Keller, a co-founder of the Big Bend Conservation Alliance, which has been organizing landowners’ pipeline opposition.

Marfa Lights literature at the bookstore. (Photo: Peter Ash Lee)

Part of the fear is that this project will change the open landscapes of this part of Texas into just another gas field: there’s a shale play underneath the Big Bend, which could entice gas companies to frack. Energy Transfer Partners originally said, too, that there wouldn’t be any compressor stations along the Trans-Pecos pipeline, but in one meeting a company representative suggested that if they did need to put in a station, south of Marfa would be an ideal location.

These stations are lit up through the night, and sometimes flare off gas—if a compressor were built, there might still be lights outside of Marfa, but they wouldn’t be mysterious.

The message of the Marfa Mystery Light Brigade is a riff on a handpainted sign, in funky red letters, that famously told visitors to “See Mystery Lights.” The Friday night gathering was only the beginning of the group’s efforts to call attention to the pipeline: Defend Big Bend is planning other “less tame” actions, too. “I want people to understand that this is a fragile place,” says Santoro. Getting out to Big Bend is a pilgrimage: the closest major airport is hours away. For the tourists that support the economy to make the journey, there has to be a little bit of mystery to draw them all the way here.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook