A Serbian Village’s 21st-Century Vampire Problem

A 15th-century engraving of a vampire attack. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

In 2012, the municipal council of the Serbian village of Zarozje issued a public health warning to residents, instructing them to place garlic on windowsills and door frames and to put holy crosses in their homes. The reason for the warning? Sava Savanovic, Serbia’s most notorious vampire, was thought to be on the loose.

After peaking in the medieval era, panics induced by suspected supernatural beings have become somewhat rare in the 21st century. But the legend of Savanovic has a strong hold over Zarozje residents.

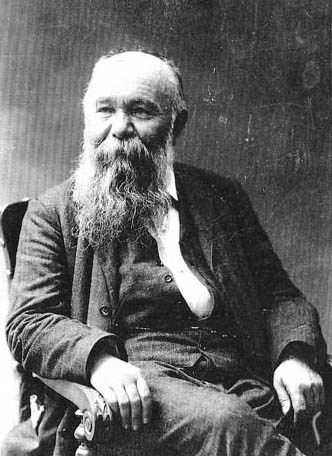

The vampire’s story goes back to before 1880, when noted Serbian author Milovan Glišić used a retelling of the traditional folklore tale as the premise for his book After Ninety Years. It purports that after being killed for murdering the woman he loved because he had been denied her hand in marriage, Savanovic is haunted a water mill located on the Rogacica River in Zarozje. Legend has it that those who came to the mill to process their grain would risk being preyed upon by the waiting vampire.

Serbian author Milovan Glišić, who wrote about Sava Savanovic in his book After Ninety Years. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

The mill that Sava Savanovic was rumored to haunt remained in operation until the 1950s, serving the needs of the small village nearby. After its closure, the Jagodić family, members of which still own the mill to this day, began to promote it as a tourist attraction because of the legend behind it and its connection with Milovan Glišić.

The building, already aged and deteriorating when it was closed, spent the next several decades in disrepair and disuse. Either out of genuine fear of disturbing Savanovic’s lair or to improve the mystique of the daylight-only tourist attraction, the Jagodić family never performed structural repairs to the rotting mill. In 2012, the decades of exposure to the elements and lack of maintenance at last caused the building to collapse.

With the noted vampire thought to be homeless after the loss of his favored haunt, the mayor and village council of Zarozje issued their unusual public warning to those living in the area. “People are worried, everybody knows the legend of this vampire and the thought that he is now homeless and looking for somewhere else and possibly other victims is terrifying people,” said Mayor Miodrag Vujetic in an interview with ABC News at the time. “We are all frightened.”

In 2012, the council Zarozje issued a public health warning to village residents instructing them to place garlic on windowsills and door frames. (Photo: glebTv/shutterstock.com)

Despite the serious tenor of the mayor’s statement, two motives—one sincere, one shady—have been reported for the public warning. The first is that the warning was issued out of a genuine belief that Savanovic was both real and dangerous. The second, more widely reported by the few Western news agencies that covered the 2012 incident, was that the warning and other official statements had been made in order to draw more tourists to the village and surrounding areas.

In his 2012 interview with ABC News, Mayor Vujetic defended his village: “I understand that people who live elsewhere in Serbia are laughing at our fears,” he said, “but here most people have no doubt that vampires exist.”

The municipality of Bajina Bašta, Serbia, where the village of Zarožje is located. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Another statement to the same effect was made by Slobodan Jagodić, one of the owners of the mill at the time of its collapse. “We were too scared to repair it, not to disturb Sava Savanovic … It’s even worse now that it collapsed due to lack of repair,” Jagodić said during an interview, also with ABC News.

Others, however, have been less ready to accept the existence of the legendary vampire. In 2008, Radoslav Jagodić, a family member of the mill owners, was interviewed about the mill in its capacity as a tourist attraction by the Serbian daily newspaper Politika. “I was never afraid. I spent nights in this watermill at least 50 times, alone,” Mr. Jagodić told Politika reporters.

In the years since Sava Savanovic’s fabled home collapsed, no deaths or diseases have been attributed to his pernicious influence—but his resurgence did result in a brief spike in garlic sales in the region.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook