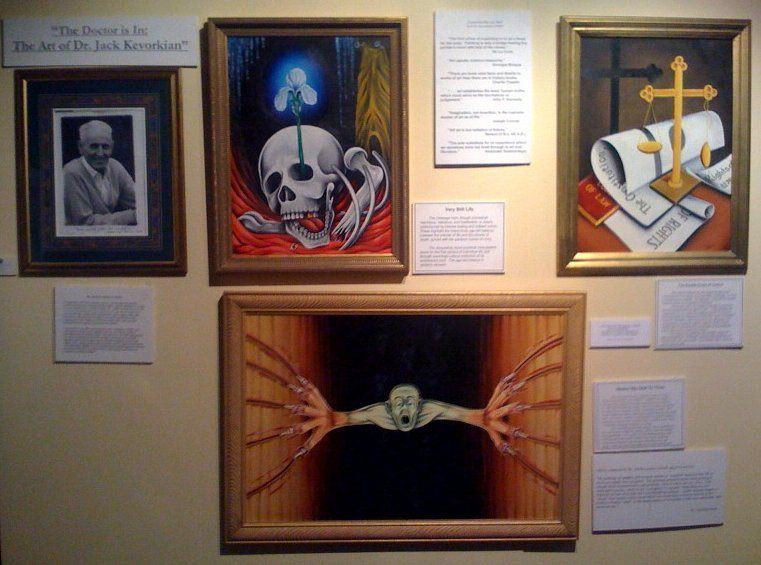

A Very Still Life: The Art and Music of Jack Kevorkian

(Photo: Hrag Vartanian/Flickr)

It’s well-known that Dr. Jacob “Jack” Kevorkian was no stranger to death. But he is less appreciated for his lust for life, which led him down just about every artistic road available, resulting in a creative life that was almost as noble and insane as his professional one.

Born in 1928, Kevorkian became a cultural phenomenon beginning in the 1980s and ’90s: a constant presence on cable TV, he assisted in least 130 suicides, leading to his eight-year stint in prison starting in the early 2000s.

But among all of the furor surrounding his work as a pioneer in the Right-To-Die movement, there was another side of the man frequently depicted as a grim reaper. Kevorkian was quite alive—in addition to his medical work, he painted, played and composed music, wrote books, and according to a close friend, even filmed a movie which has been lost to the ages.

According to Neil Nicol, a close friend and colleague of Kevorkian, he “just tried to experience everything in life.”

“He did more than anybody I’ve ever known,” says Nicol, “Art was just one of the things he took his hand to.”

Very Still Life (Images courtesy of Neal Nicol unless otherwise noted)

The man who would become Dr. Death began painting in the early 1960s, when he and Nicol worked together at what was then the Pontiac General Hospital. It was during this time that Kevorkian enrolled himself in an adult education course on oil painting. As Nicol tells it, “[everyone else was painting] apples and oranges, and bowls, and landscapes, and stuff like that. Jack did his first painting, called ‘Very Still Life.’ It was a picture of a skull with an iris growing up out of the eye socket.”

After creating what would become possibly the most iconic image of his art with “Very Still Life”, he continued to paint, moving on to works inspired by clinical symptoms with titles like “Nausea”, “Fever”, “Coma”, and “Paralysis”. He also created satirical portraits inspired by religious holidays, specifically Easter and Christmas.

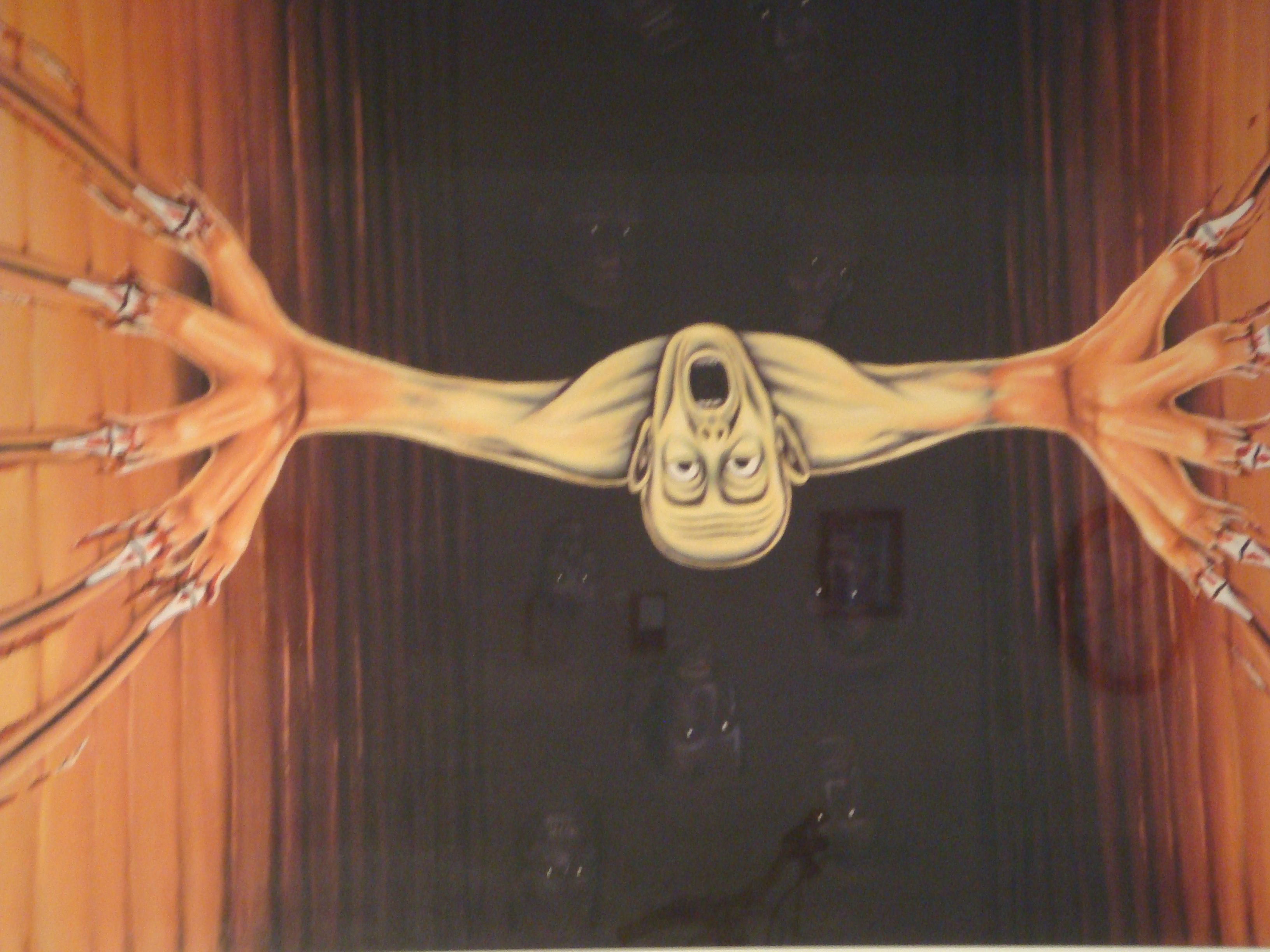

In fact, while the imagery of many Kevorkian’s paintings was seen as morbid, nearly all of them had a sort of pitch black humor lining their thought-provoking message. For instance, in “Nearer My God To Thee,” a terrified man can be seen falling into a black abyss of indifferent faces, his fingers scraping desperately on the walls of the rift, exposing the bloody bone beneath. But Kevorkian himself described the message of the painting as such:

How forbidding that dark abyss! How stupendous the yearning to dodge its gaping orifice. How inexorable the engulfment. Yet, below are the disintegrating hulks of those who have gone before; they have made the insensible transition and wonder what the fuss is all about. After all, how excruciating can nothingness be?

Nearer My God To Thee

This is not to say that all of Kevorkian’s paintings were gruesome. He also created a handful of fairly straightforward works, like portraits of his parents, and of Johann Sebastian Bach. He further honored his love of music with a colorful painting of a simple musical note entitled, “Chromatic Fantasy.”

Maybe the most amazing thing about Kevorkian’s paintings is that, according to Nicol, none of the surviving works are the originals. In the late 1970s Kevorkian moved out to California where he took a pair of part time jobs in Long Beach. After leaving those initial jobs after disputes with his superiors, he devoted his life and life savings to a failed film version of Handel’s Messiah. Set to the famed oratorio, the film would have explored the biblical themes of the music. Unfortunately, his quest to create this film drove him to the poorhouse, and Kevorkian was living in his car by 1982.

Both his original paintings and all the work that had been completed on his film were placed in a storage locker, the payments on which eventually lapsed. All of the paintings and all traces of his film were lost, likely ending up in a garbage dump. The only remaining record of the film seems to be Nicol’s own vague memory of the trailer:

It was about Jesus, and shepherds, and the Bible, apparently. [The trailer] showed a picture of someone dressed like Jesus, and another woman dressed as Mary. After that he started to run out of money, and he wanted to find clips that were done by the major studios, but that weren’t going to be used in the movies. So he started to buy those and integrate them into the Messiah. So it was kind of a disjointed presentation.

After returning to Michigan to begin his work on death counseling in earnest, Kevorkian decided to remake the paintings that had been lost, but had no visual record of them. Luckily, he was able to locate someone who had taken Kodachrome photos of many of the paintings, and Kevorkian set out to recreate a number of them. It doesn’t seem to be known how many, if any, Kevorkian failed to repaint, but according to Nicol, all of the works extant today are the second of their kind, and there may have been some that were lost forever.

The Gourmet

Painting and film were not Kevorkian’s only passion, as he also dabbled in musical composition and performance. Kevorkian played flute and organ and actually released a full album in 1997, entitled A Very Still Life, appropriating the name of his first painting. The 12-track LP was a collection of jazz-funk songs comprised almost exclusively of Kevorkian’s original compositions. The album was completely instrumental with Kevorkian on flute and organ, sounding a bit like Vince Guaraldi’s A Charlie Brown Christmas by way of Angelo Badalamenti’s Twin Peaks soundtrack. Only 5,000 copies of the record were ever produced but it can still be found on YouTube.

In 1999, Kevorkian was convicted of second-degree homicide by a Michigan court and was sentenced to 10-to-25 years in prison. While he served only eight years of his sentence before being released, his incarceration may have spelled the end to Kevorkian’s artistic endeavors. Nicol says that while Kevorkian thought about playing music or painting while he was in prison, it was hard to schedule a time in the crowded facilities, and “[Kevorkian] said it was just not worth his time.” Discussing how Kevorkian felt about his own works, Nicol says, “He bored easily. Once he’d get bored with them, he didn’t want to do it any more. He was very enthusiastic about it when he’d get started, but then once he got bored with it, he’d just stop doing it.”

Kevorkian died from a blood clot in June, 2011.

He did achieve some commercial success, post-death, from his artwork: in 2014, a gallery was selling his painting for $45,000 a pop, claiming that the unsold work would go to the Smithsonian. This sale came after years of legal wrangling, as the work had formerly been housed in Armenian Library and Museum of America in Watertown, Massachusetts.

Artistically, though, Kevorkian’s work remains enigmatic. It’s not easy to find a through line in Kevorkian’s shaggy body of creative output. From a bloody painting that uses decapitation as a metaphor to war, to the filming of a biblical opera, to some noirish jazz licks, Kevorkian seemed to follow whatever muse struck him. While his words are a bit opaque, his description of his first painting, ”Very Still Life” seems to nicely sum up his body of work:

The message here, though somewhat capricious, nebulous and indefinable, is clearly underscored by intense feeling. Brilliant colors highlight the melancholoy age-old balance between the warmth of life and the iciness of death, spiced with the sardonic humor of irony. The disquieting mood portends inescapable doom for the frail symbol of individual life and seemingly callous extinction of its evanescent aura. The age-old balance is certainly skewed.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook