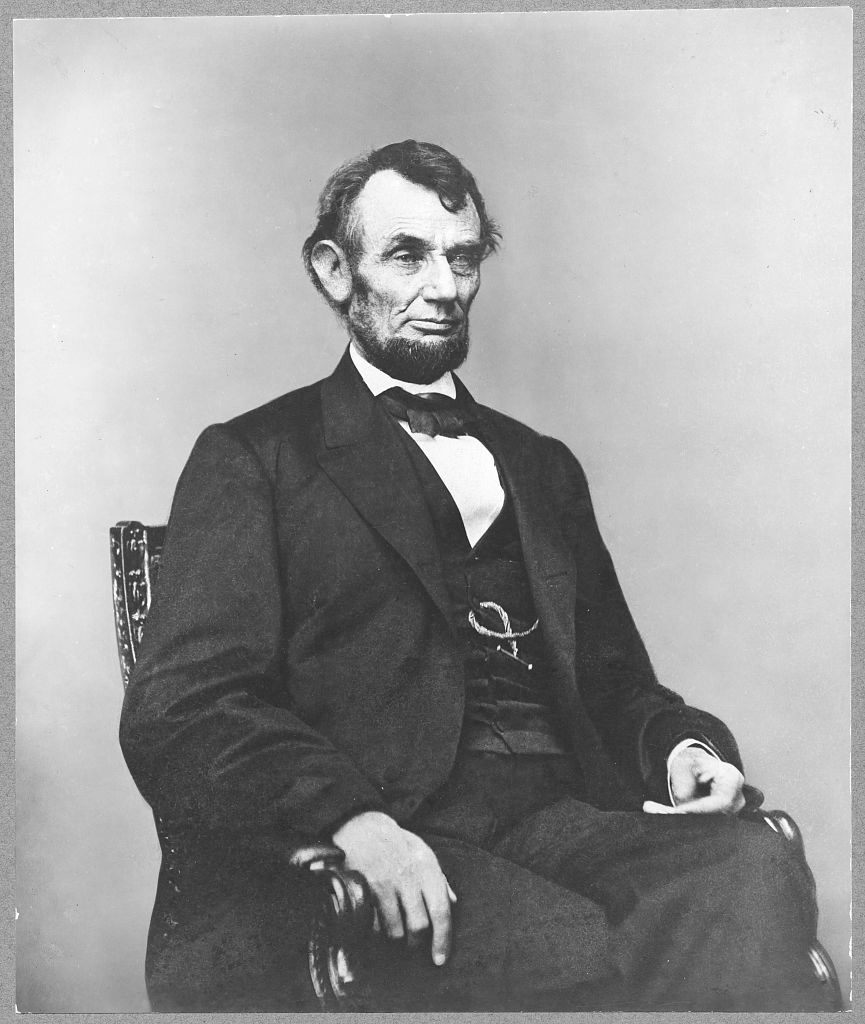

The Great Lengths Taken to Make Abraham Lincoln Look Good in Portraits

One famous image of the president features a body that isn’t his.

Abraham Lincoln had a problem. During his 1860 campaign as a Republican candidate for the American presidency, in an era after the birth of the photograph but before its widespread dissemination in the media, many of the country’s citizens could only guess at what he looked like.

Rumors of his ugliness proliferated. The North Carolina newspaper The Newbern Weekly Progress wrote that Lincoln was “coarse, vulgar and uneducated,” while the Houston Telegraph opined that he was “the leanest, lankiest, most ungainly mass of legs, arms and hatchet face ever strung upon a single frame. He has most unwarrantably abused the privilege which all politicians have of being ugly.”

One woman, Mary Boykin, claimed Lincoln was “grotesque in appearance, the kind who are always at the corner stores, sitting on boxes, whittling sticks, and telling stories as funny as they are vulgar.” In fact, many Democrats sang an anti-Lincoln rallying cry that concluded with: “We beg and pray you— Don’t, for God’s sake, show his picture.”

Though the rumors of Lincoln’s ugliness stayed mostly within Democratic circles, Lincoln was not anxious to let the idea spread. So he turned to Mathew Brady, a well-known photographer with a studio on Pennsylvania Avenue. In many ways, Brady was perfect: though Brady himself had bad vision and did not take many of his own photos, he “conceptualized images, arranged the sitters, and oversaw the production of pictures.” Plus, according to the New York Times, Brady was “not averse to certain forms of retouching.”

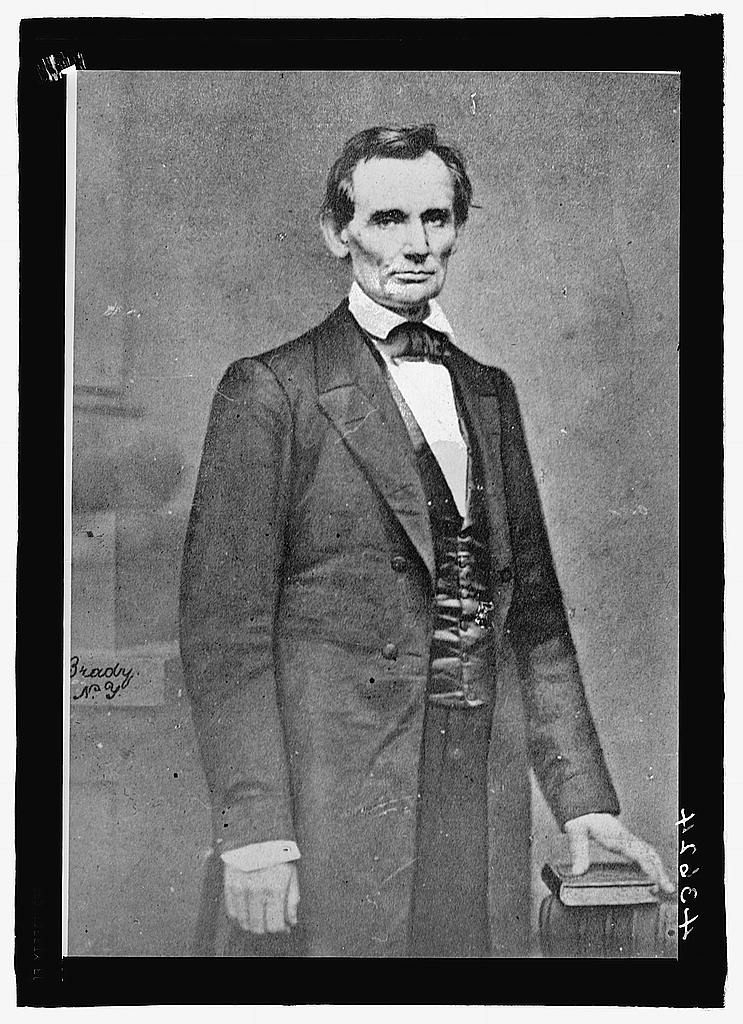

In February 1860, just before Lincoln gave the Cooper Union Address that would help secure him the Republican presidential nomination, Brady had Lincoln pose for what would soon become one of the first widely disseminated photographs of the future president.

The background is bare: Lincoln places his hand on two books, his eyes on the viewer; behind him is a column and a neutrally colored wall. But to quash once and for all the rumors of Lincoln’s ugliness, Brady added some special effects. He focused excessive amounts of light on Lincoln’s face in order to distract from his “gangly” frame. He had the future president curl up his fingers so that their remarkable length would go unnoticed. Brady even “artificially enlarged” Lincoln’s collar so that his neck would look more proportional.

(The neck critique, apparently, was a popular attack line on Lincoln’s appearance—after attending Lincoln’s inauguration in 1861, one Virginia man wrote that Lincoln “is a much better looking man than he is represented in the papers to be, not being so extraordinarily tall, nor having such a very long neck either.”)

Soon after it was taken, the Brady photo was plastered across American newspapers, including Harper’s Weekly, and featured on numerous postcards. In some reproductions, artists tinkered further with Brady’s creation; apparently, “subsequent versions of this famous portrait also show that artists smoothed Lincoln’s hair and subtly refined his features.” Though this kind of tinkering is familiar today, with public figures enduring intense pressure to look their best at all times, it was quite new in 1860.

Regardless, the photo received such a rapturous reception that Lincoln later said, “Brady and the Cooper Institute made me President.”

After his election, Lincoln kept returning to Brady for portraits. In all, Brady produced more than 30, including the images that are now memorialized on the penny and the five-dollar bill.

But Brady’s tweaks of Lincoln’s appearance were not the most conspicuous edits made to his photographs.

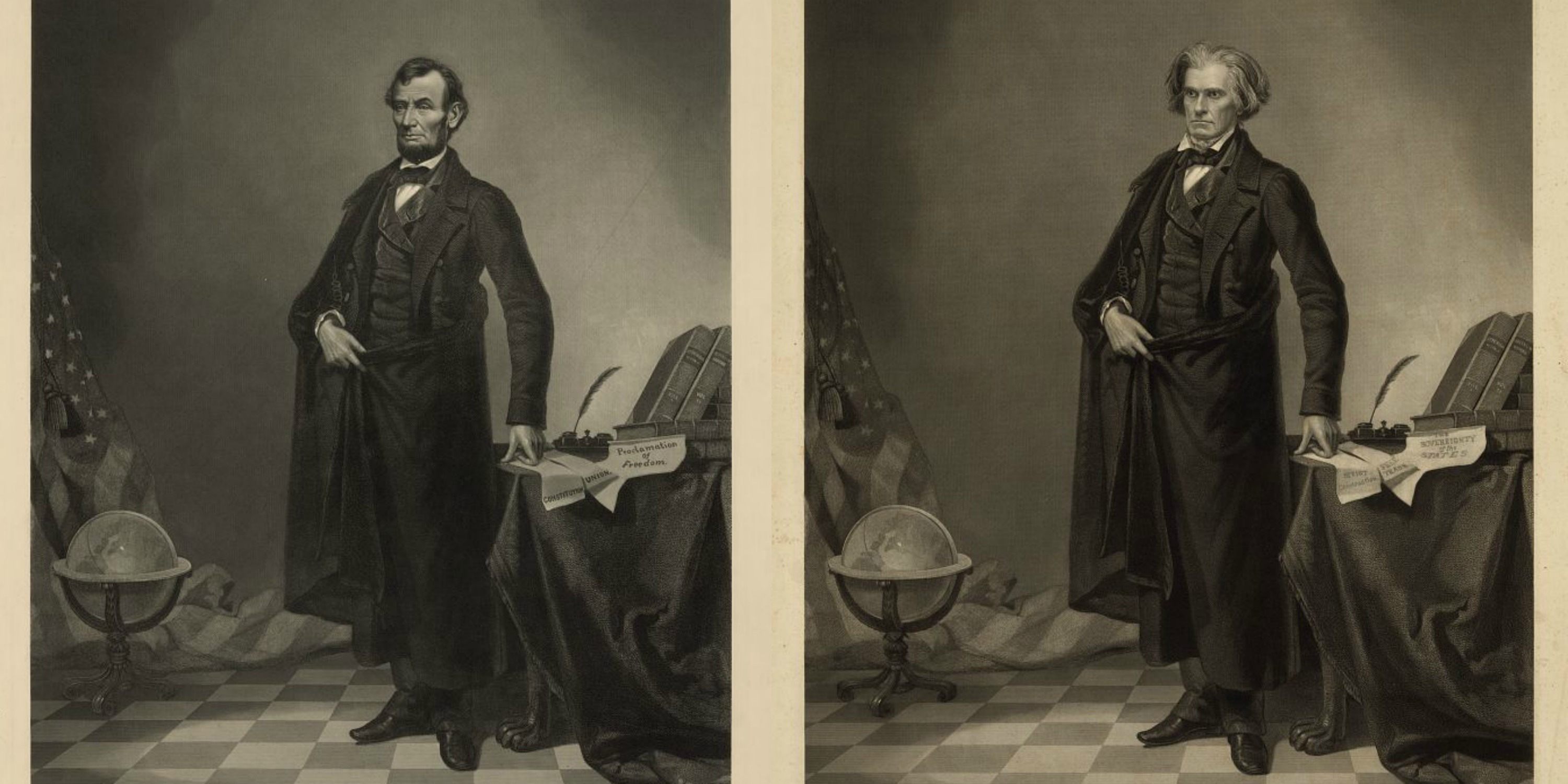

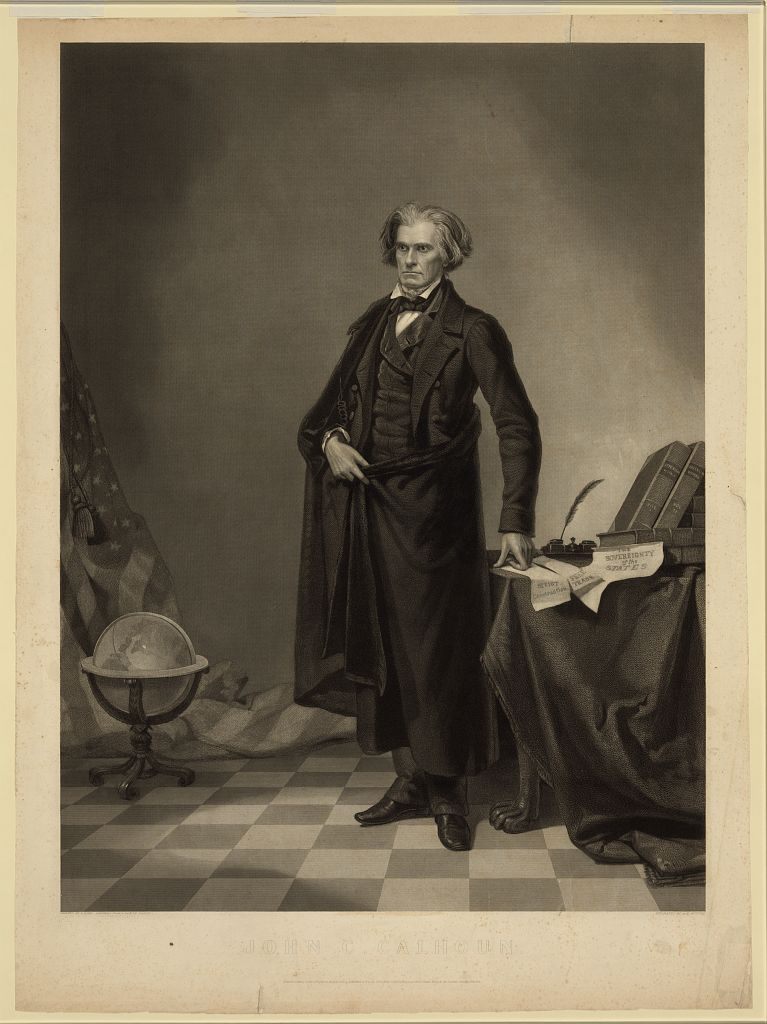

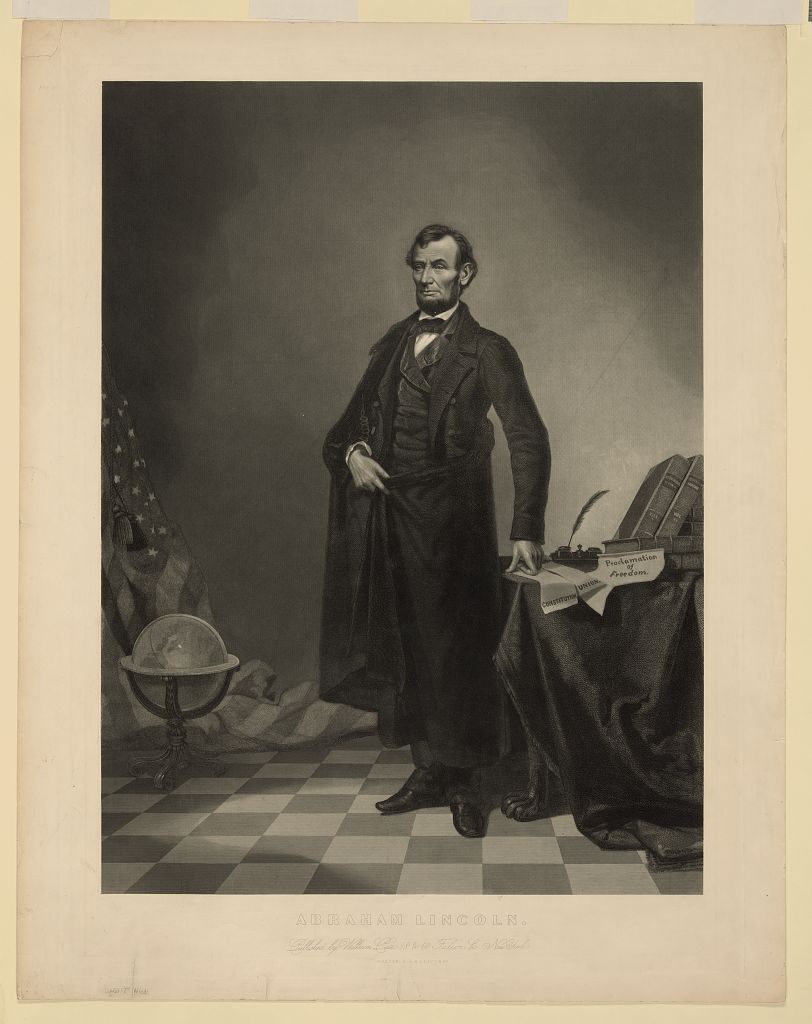

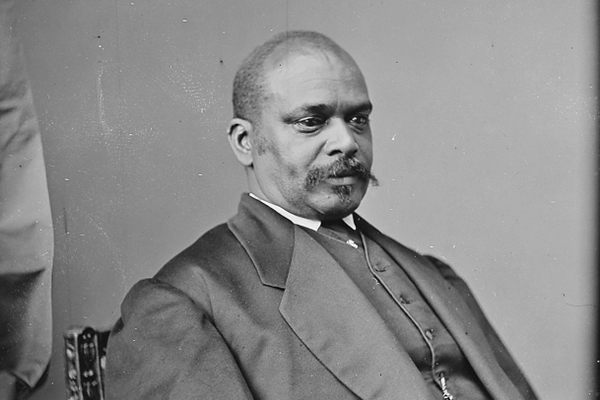

After Lincoln’s assassination, there was a dearth of “heroic-style” pictures of the president. So one portrait painter got creative. On a print of the late president, Thomas Hicks superimposed Lincoln’s head onto the body of John C. Calhoun—the virulent racist and slavery proponent who did not exactly see eye-to-eye with the 16th president.

Engraver A.H. Ritchie created the Calhoun image in 1852. The original included the words “strict constitution,” “free trade,” and “the sovereignty of the states” on the desk papers. But when it was altered to feature Lincoln instead, the words were changed to “constitution,” “union,” and “proclamation of freedom.”

For a century, no one noticed. The print* was only recently revealed to have been faked.

Photojournalist Stefan Lorant was compiling photos of Lincoln for his book Lincoln, A Picture Story of His Life (first published in 1957, then revised in 1969) when he discovered something odd: in the Hicks print, Lincoln’s mole was on the wrong side of his face. After some investigation, he realized that Lincoln’s face in the print exactly matched his face in Brady’s five-dollar bill photo—except in the print Lincoln’s face was flipped, making Lincoln’s mole show up on the opposite side.

Apparently, Hicks hadn’t noticed this discrepancy when superimposing the picture onto Calhoun’s body.

But this high-profile precursor to a Photoshop edit was not only used on photos of Lincoln. Brady often altered images: for a group photo of General William Sherman’s staff, he edited in a member who couldn’t attend. In fact, Brady even asked soldiers to “pretend they were dead” for some of his famous Civil War portraits.

At least Lincoln, despite all of the posing Brady had him do, never had to lie on a battlefield and feign death for the sake of a Kodak moment.

*Correction: We originally referred to the Calhoun/Lincoln image as a “photo.” It is a print featuring a photo of Lincoln’s head superimposed on an engraving.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook