Ada Blackjack, the Forgotten Sole Survivor of an Odd Arctic Expedition

In the early 1920s, 23-year-old Blackjack endured a two-year stay on frosty Wrangel Island.

When Ada Blackjack set sail in 1921 for a remote speck of land north of Siberia, the petite Inupiat woman was an unlikely Arctic heroine. In her role as the seamstress for an expedition comprised of four men and a female cat named Vic, Blackjack was assured that during her one-year contract sewing survival gear on Wrangel Island, she would be well fed and cared for without needing to participate in the grueling day-to-day work of Arctic survival.

But by the time a rescue ship crested the horizon nearly two years later, Blackjack, who would come to be known as “The Female Robinson Crusoe,” was the only member of the party still alive—that is, apart from Vic. The shy tailor with the crippling fear of polar bears had taught herself to shoot and trap to stave off the constant threat of starvation, and when she strode out to meet her rescuers in a resplendent reindeer parka she had stitched herself, her gaunt face held a triumphant smile.

Blackjack—née Ada Deletuk—was born in 1898 in Spruce Creek, Alaska, a remote settlement north of the Arctic circle near the gold rush town of Nome. History has largely forgotten her, though Jennifer Niven’s 2004 biography Ada Blackjack: A True Story of Survival in the Arctic painted a comprehensive picture of her life. While Blackjack was Inupiat, she was not raised with any knowledge of hunting or wilderness survival. She was instead brought up by Methodist missionaries who taught her enough English to study the bible, and who instructed her in housekeeping, sewing, and cooking white-people food.

At the age of 16, she married Jack Blackjack, a local dog musher, and together they had three children—two of whom died—before Jack deserted Ada on the Seward Peninsula in 1921. The abandoned Blackjack walked 40 miles back to Nome with her five-year-old son, Bennett; when he was too tired to walk, she carried him. The boy suffered from tuberculosis and general poor health, and Blackjack lacked the resources to properly care for him. Destitute, she placed Bennett in a local orphanage, vowing that she would find a way to make enough money to bring him back home.

It was during this time that Blackjack heard word of an expedition heading for Wrangel Island: they were seeking an Alaska Native seamstress who spoke English.

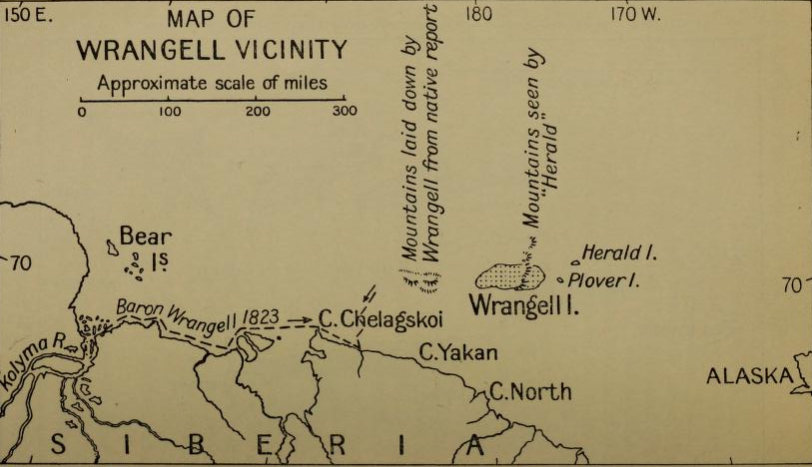

The expedition, organized by the charismatic Arctic explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson, was at best an ill-conceived venture; at worst, it was a willfully negligent act of astonishing hubris. Using the pull of his celebrity as a seasoned explorer, Stefansson assembled a team of four starstruck young men—Allan Crawford, 20, Lorne Knight, 28, Fred Maurer, 28, and Milton Galle, 19—to claim Wrangel Island for the British Empire—even though Britain had never shown the slightest interest in wanting it. Though Stefansson picked the team and funded the mission, he never had any intention of joining the party himself and sent his woefully inexperienced team north with only six months of supplies and hollow assurances that “the friendly Arctic” would provide ample game to augment their stores until a ship picked them up the following year.

Blackjack had many misgivings about shipping out with an expedition of four men, especially as she had initially been promised she would be just one of many Indigenous Alaskans in the party. But the odd jobs of sewing and housekeeping she was picking up in Nome were never going to be enough to bring Bennett home, and the Wrangel Island expedition promised a salary of $50 a month—an amount that was, to Blackjack, an unheard-of sum. And so even after the rest of the hired Inuits backed out, on September 9, 1921, Blackjack boarded the Silver Wave with Crawford, Knight, Maurer, Galle, and the ship’s cat, Victoria.

For the first year on Wrangel Island, the land lived up to Stefansson’s promises, but as summer came to an end, the once-plentiful game disappeared and the pack ice closed in with no sign of a ship. Unbeknownst to the party, Teddy Bear, the ship chartered to pick them up, had been forced to turn back due to impenetrable ice. As the weather turned, the expedition faced the reality that their inadequate stores would have to last another year.

By the beginning of 1923, the situation had turned dire: the party was starving, and Knight was extremely ill with undiagnosed scurvy. On January 28, 1923, Crawford, Maurer, and Galle made the decision to leave Blackjack to care for the deathly ill Knight and set out on foot across the ice to Siberia in search of help. They were never seen again.

For six months, Blackjack was alone with Knight. She served as “doctor, nurse, companion, servant, and huntswoman in one,” said the Los Angeles Times in 1924. “Ada was woodsman, too.” The dying man projected the rage he felt over his helplessness onto her, criticizing her constantly for not taking better care of him. Blackjack did not outwardly allow his blows to land, but confided in her diary, “He never stop and think how much its hard for women to take four mans place, to wood work and to hund for something to eat for him and do waiting to his bed and take the shiad [shit] out for him.”

When Knight passed, Blackjack duly recorded the event on Galle’s typewriter, writing:

“The daid of Mr. Knights death

He died on June 23rd.I dont know what time he died though

Anyway I write the daid. Just to

let Mr Steffansom know what month he

died and what daid of the monthwritten by Mrs. Ada B, Jack.”

After Knight’s passing, Blackjack refused to fall into despair and instead threw herself ferociously to the task of surviving in order to be reunited with her son. Having neither the physical strength nor emotional fortitude to bury Knight’s corpse, she left him resting on his bed inside of his sleeping bag and erected a barricade of boxes to protect his body from wild animals. As Jennifer Niven wrote in her Ada Blackjack biography, she “moved into the storage tent to escape the smell of decay … she drove driftwood into the ground to bolster the tattered walls and ceiling of the tent. She built a cupboard out of boxes, which she placed at the entrance, and in this she stored her field glasses and ammunition.” Most importantly, Blackjack built a gun rack above her bed so that she would not be caught by surprise if polar bears ventured too close to camp.

For three months, Blackjack was alone. She learned how to set traps to lure white foxes, taught herself to shoot birds, built a platform above her shelter so she could spot polar bears in the distance, and crafted a skin boat from driftwood and stretched canvas after the one initially brought to the island was lost in a storm. She even experimented with the expedition’s photography equipment, taking pictures of herself standing outside of camp.

On August 20, 1923, almost two years after first landing on Wrangel Island, the schooner Donaldson crested the horizon to rescue the persevering seamstress, who was doing quite well on her own. “Blackjack,” the crew noted, “mastered her environment so far that it seems likely she could have lived there another year, although the isolation would have been a dreadful experience.” As news of the expedition’s tragic end spread, Blackjack found herself at the epicenter of a flurry of press attention lauding her as a hero and praising her for her courage. But the quiet seamstress shied away from the attention and titles, insisting that she was simply a mother who had needed to get home to her son.

Ada was reunited with Bennett and used her payment—which was less than she had been promised—from her time on Wrangel Island to seek treatment for his tuberculosis in a Seattle hospital. She later had a second son, Billy, and returned to live in Alaska. But despite this seemingly happy ending, Blackjack’s remaining years were tinged with pervasive sadness and poverty. While Stefansson and others profited from the story of the tragic expedition, Blackjack saw none of that money, and smear campaigns against her character later emerged claiming that she had callously refused to care for Knight. Bennett’s health issues were never fully resolved, and he died of a stroke in 1972 at the age of 58. Blackjack followed her son roughly a decade later, passing away in a nursing home in Palmer, Alaska at the age of 85; she was buried by Bennett’s side.*

*This story was updated to include more information about what happened after Blackjack was reunited with her son.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook