The Scandalous Witch Hunt That Poisoned 17th-Century France

The Affair of the Poisons was one to remember.

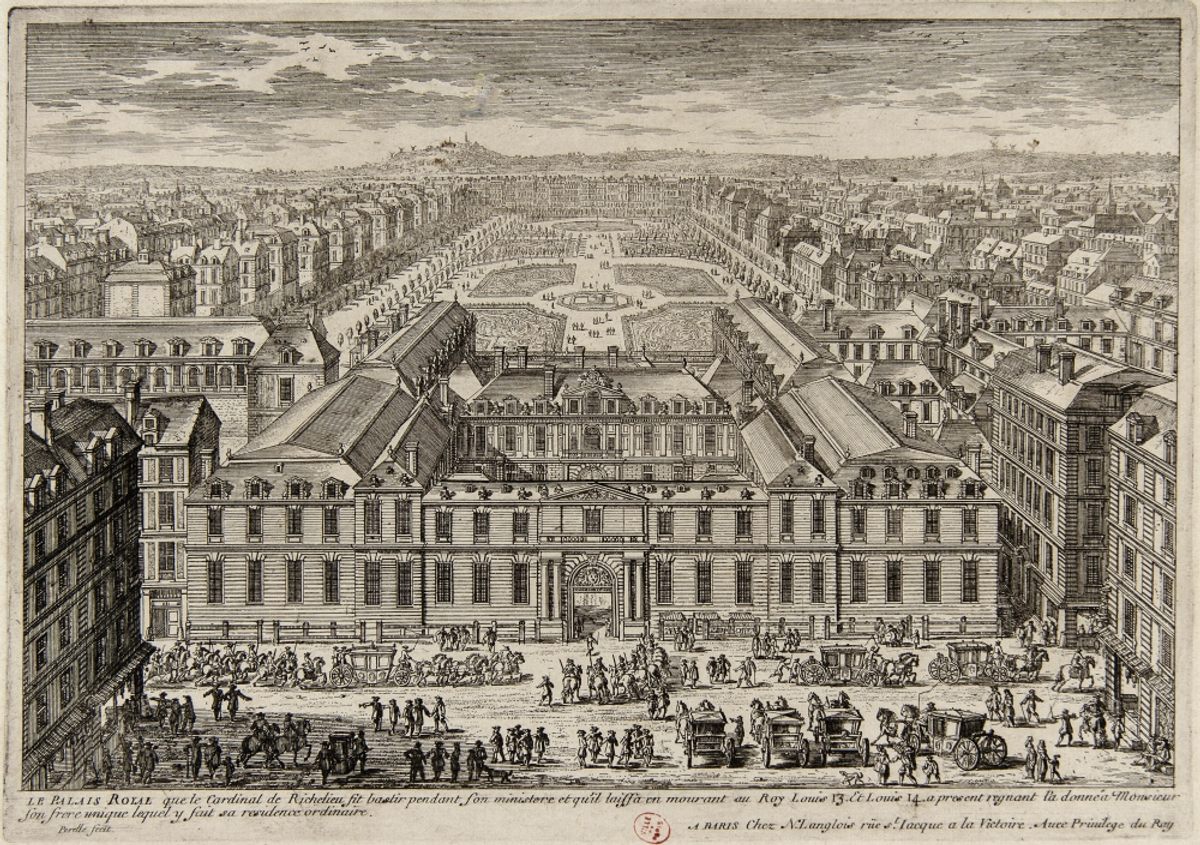

Beneath the gilt and glamor of King Louis XIV’s palace at Versailles wafted a terrible smell. The French Sun King had spent vast fortunes to transform an unassuming hunting lodge into his own golden wonder court, one of the most astounding palaces in the world. But the building’s location, far from a river, made sewage disposal challenging, and its marshy foundations gave off a rank odor. A lack of facilities apparently led courtiers to defecate around the palace and grounds with abandon. The few bathrooms there were poorly maintained and often overflowing with waste.

There was another, more sinister stench discernible there as well, one more troubling than the commonplace stink of humanity. In the late 1660s and early 1670s, influential members of the French nobility began to die, unexpectedly and close upon one another. Autopsies showed their insides blackened and corroded. A fever for poisoning and witchcraft seemed to have infected the court, and in 1679 Louis XIV was forced to establish a special tribunal—a Chambre Ardente, or “burning room”—to investigate and prosecute the murders.

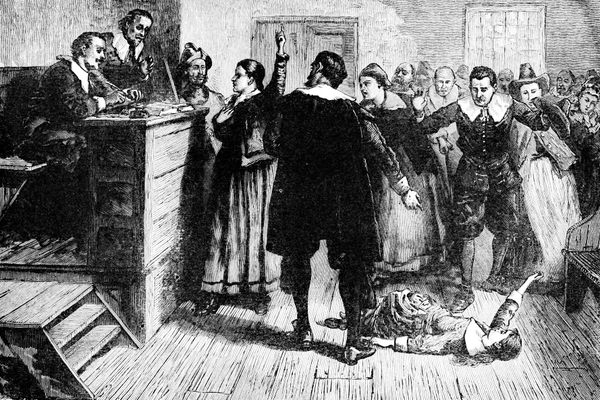

The “Affair of the Poisons,” as it came to be known, is a misleading name for one of the largest witch trials in modern history. Over just five years, from 1677 to 1682, 319 subpoenas were issued, 194 individuals arrested, and 36 executed (with perhaps dozens more dead from suicide, or in prison or exile). In total, it claimed between two and three times as many lives as the Salem witch trials across the Atlantic, 10 years later. It began with what appeared to be an isolated case, but then door after door after door opened, eventually implicating rich and poor alike.

“What’s noteworthy about the Affair is that it shows how people from the top to the bottom of the social spectrum participate in a shared magical understanding of the world,” says cultural historian Lynn Wood Mollenauer, of the University of North Carolina Wilmington. “This could only have been possible in a very religious society, because the power that’s attributed to magical ritual and practice almost entirely relies on Catholic sacerdotals and rituals—the Eucharist. It says something profound about religiosity.” The Affair was confusing, complex, convoluted—and persistent because everyone, however powerful, had a common fear of witchcraft, poisoning, and the unknown.

This strange series of events took place against a backdrop of extreme disparity, both economic and social. While many outside the court’s walls lived simple, even impoverished lives, those within could blow an entire fortune in single morning at the gambling table. And, while Louis XIV conspicuously attended daily Catholic mass, he and his court were described as the most libertine in Europe. The Spanish noble the Duke of Pastrana was more direct: The court, he said, was “a real brothel.” It was politically tempestuous and unforgiving, and its ruler a ruthless, albeit charming, womanizer.

In most cases, writes Anne Somerset, author of The Affair of the Poisons: Murder, Infanticide and Satanism at the Court of Louis XIV, “the investment required to live at court far outweighed the gains.” To keep up appearances, aristocrats squandered lavish sums on “fine clothes, household expenses, servants and carriages,” even while income from their lands was shrinking. Ruin loomed over every extravagance. Excess bred boredom, which bred a taste for transgressive pastimes: Fortune-telling and palm-reading joined gambling as popular court activities, against a backdrop of superstition and belief in witchcraft. Murder, in this setting, could be just another diversion. And this diversion didn’t involve blades and blood, but poison.

Marie de Brinvilliers

It was in this context that, in 1672, French police were called to investigate a break-in at a laboratory belonging to one Gaudin de Sainte-Croix, a devilishly handsome, and recently deceased, young army officer. There, they found a red leather trunk of letters, vials, and mysterious substances. The contents of the trunk seemed to link Sainte-Croix’s two passions: his lover, the very married Marie de Brinvilliers, and poisoning. While incarcerated in the Bastille for three months for his affair with de Brinvilliers, in 1663, Sainte-Croix apparently befriended Italian Egidio Exili, rumored to have been a master poisoner.

Before vanishing, Exili seems to have taught the Frenchman quite a bit. At the time, poisons were poorly understood, and hard to detect as a cause of death. Consequently, many specific crimes likely went unpunished, much to the fright of the French people. In the xenophobic French court, it was often seen as an Italian art, dating back to the time of Catherine de Medici. It was said that the Italians had found a way to poison a stray glove—further alarming the populace.

In the years before his death, possibly of an accidental self-poisoning, Sainte-Croix “perfected” his art, which involved both trying to turn base metals into gold and trying to create an odorless, tasteless, untraceable poison. The first was out of reach—the second was not.

Sainte-Croix and de Brinvilliers shared their passions, and began to test this new substance (likely arsenic), allegedly by lacing cakes and other sweets with it, and giving them to unsuspecting patients in a nearby public hospital. Seemingly, the thrill was their only motive. Letters in the trunk unambiguously implicated de Brinvilliers in the recent deaths of her father and two brothers as well, a sad turn of events that put her in line to inherit a fortune. Upon the discovery of the trunk, she fled Paris for the countryside and then abroad, where she managed to remain on the lam for four years before being arrested in Belgium.

Historians seem to struggle to reconcile de Brinvilliers’s “uncommon physical attractions” with her toxic pastime. A 1911 biography by Hugh Stokes is especially onanistic. “Her soft smile, her blue eyes, her graceful figure,” he writes, “concealed the unbridled passions of a tigress.” Eventually, in a letter found in her convent cell, she confessed to having attempted to poison her sister, daughter, and husband.

Stokes reads the confession as the work of a dangerous sociopath. “Heart had she none, not even for the men she loved,” he writes. Modern observers are more inclined to see these actions as the work of someone who was deeply damaged, perhaps because of the prolific childhood sexual abuse at the hands of her brother she mentions in the letter. Somerset posits: “This might explain, even if it cannot excuse, her extraordinary callousness and psychopathic tendencies.”

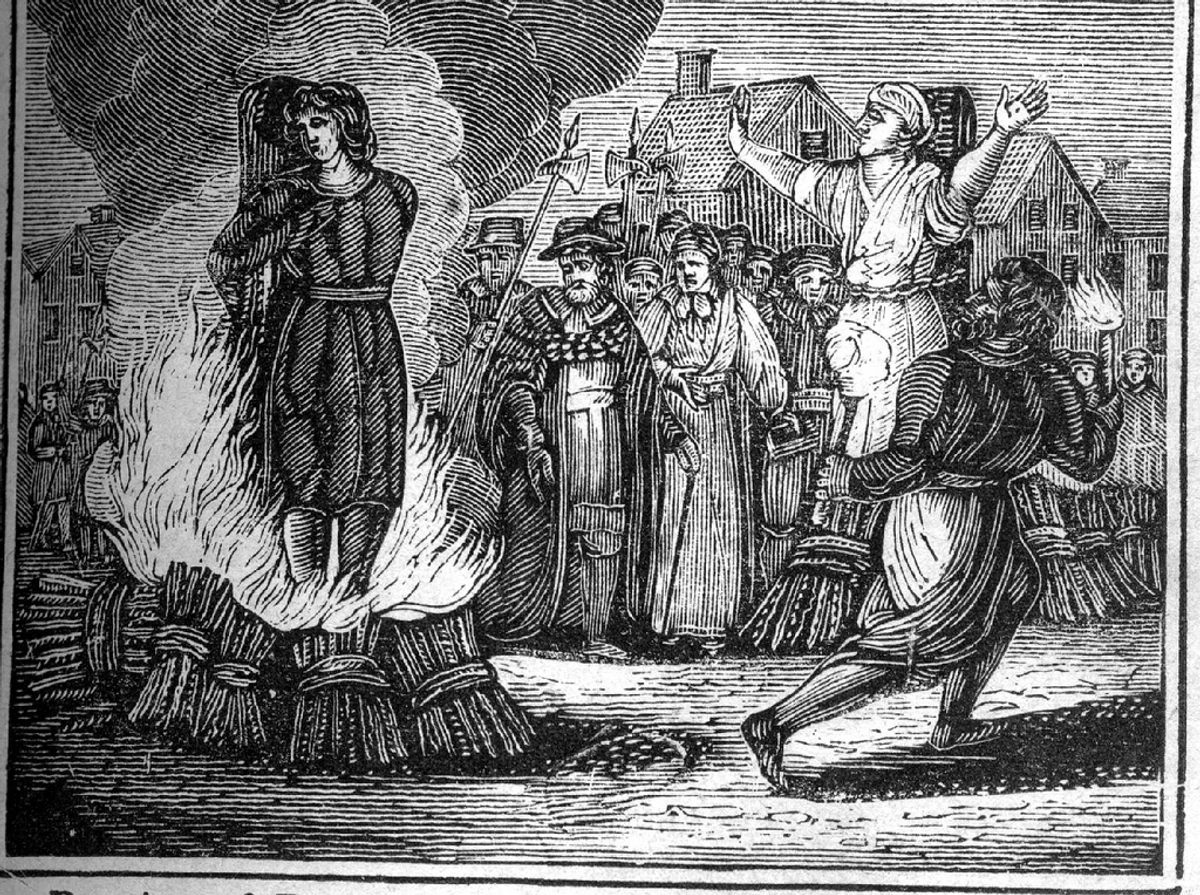

Later, de Brinvilliers attempted to distance herself from this admission, claiming feverish madness, but it was much too late. She was found guilty and subjected to “water torture” to force her to name accomplices. Stripped naked and bound, she had 24 pints of water forced down her throat. (Looking at the numerous buckets, de Brinvilliers is said to have remarked: “No doubt all this water is to drown me in? I hope you don’t suppose that a person of my size could swallow it all.”) She was then beheaded and burned at the stake, and had her ashes cast into the wind.

The beauty and wickedness of this lurid case captured Paris’s imagination. Madame de Sévigné, an aristocrat famous for her witty letters, was present on the day of de Brinvilliers’s execution. “Never has Paris seen such crowds of people,” she later wrote. “Never has the city been so aroused, so intent on a spectacle.”

But, more than a spectacle, the revelations were cause for anxiety, even terror, at court. Just before she died, de Brinvilliers allegedly said, “Out of so many guilty people, must I be the only one to be put to death? … Half the people in town are involved in this sort of thing, and I could ruin them if I were to talk.” De Sévigné wrote jokingly that, since the citizens of Paris had inhaled de Brinvilliers’s wicked ashes, “with such evil little spirits in the air, who knows what poisonous humor may overcome us?” Indeed, Paris was about to go mad. In the next seven years, dozens of nobles would perish, by torture, suicide, execution, or poison.

Following the execution, prior deaths of prominent figures, which had not seemed unusual at the time, were looked upon with fresh eyes. De Brinvilliers, apart from being beautiful, was also noble-born. If a woman of her stock could be guilty of such crimes, no one was above suspicion. At court, Louis XIV already harbored particular anxieties about assassination, which concerns about poisoning exacerbated. A possibly apocryphal story suggests that vichyssoise is served cold because, by the time it arrived at the King’s table, it had been before both his taster and his taster’s taster.

An alarmed king appointed Gabriel Nicolas de la Reynie, Lieutenant General of the Paris Police, to oversee an investigation. Previously charged with the Sisyphean task of cleaning up Paris, La Reynie had earned fame and respect for implementing, in a matter of months, “city safety, gun control … street cleaning, flood and fire control,” and even a mud tax. This investigation promised a whole other challenge for him, since it was impossible to know quite how much of the iceberg was beneath the surface, even for a man intimately familiar with the deepest machinery of the city’s society.

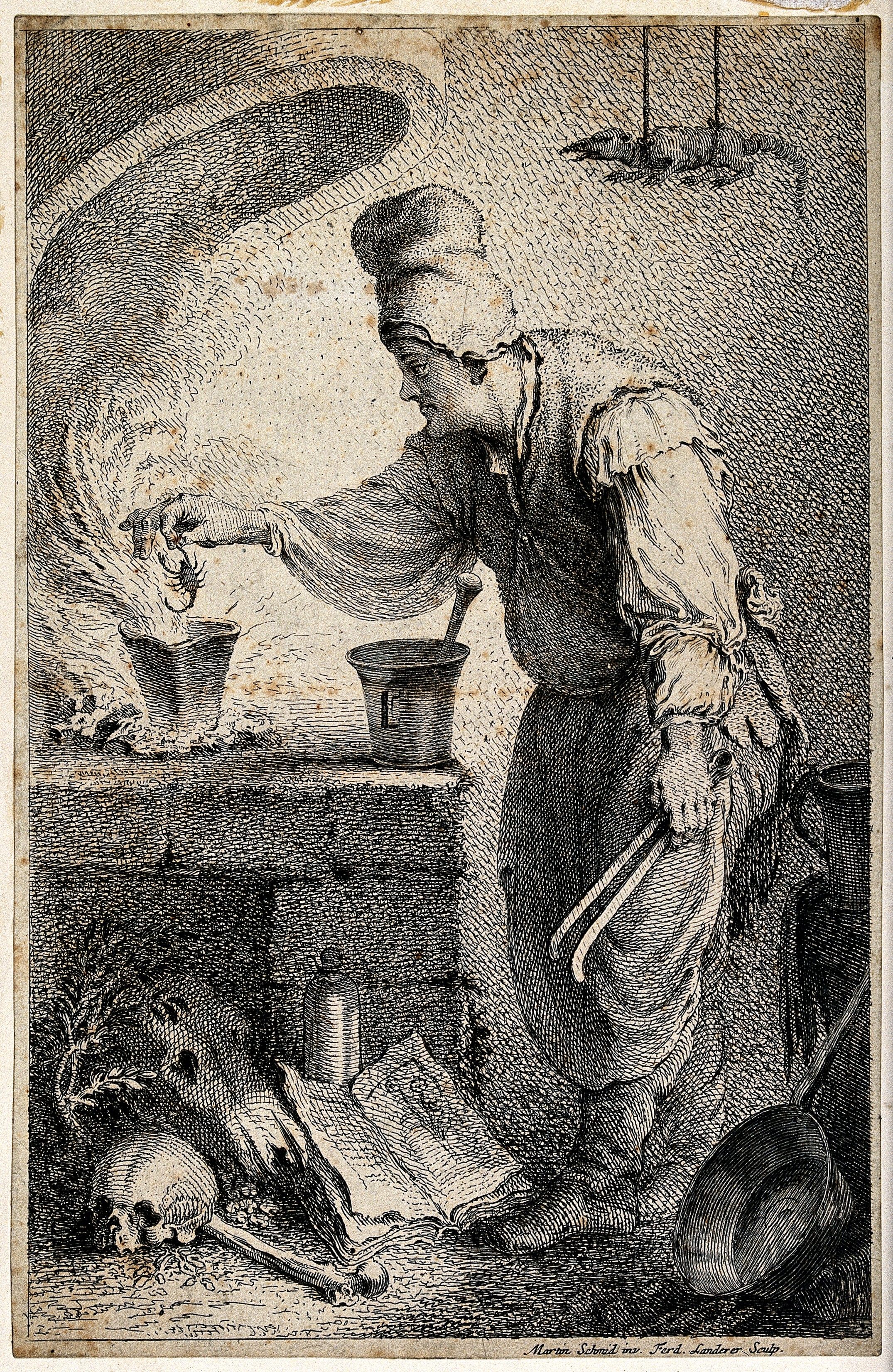

It was not long before arrests began. Police descended upon alchemists, counterfeiters, and poisoners, amid rumors of a royal poisoning plot. The Affair was about poison, to be sure, but it was also about witchcraft—the two were bedfellows. According to historian Frances Mossiker, police uncovered troves of lethal chemicals (arsenic, nitric acid, mercuric chloride), equipment (furnaces, forceps, cauldrons, vials), and foul natural ingredients (flowers, deadly nightshade, “blobs of hanged-man’s fat, nail clippings, bone splinters, specimens of human blood, excrement, urine, [and] semen”). It looked as much like a plague of dark magic and poisoning together, and rumors abounded. Then, in 1679, La Reynie made another hugely important arrest, from another stratum of society, an arrest that gave him the rattling keys to Paris’s criminal underworld. Later, this enabled a full-scale investigation.

Catherine Monvoisin

Catherine Monvoisin, also known as La Voisin, was apprehended outside her parish church on March 12, 1679. By profession, she was a “divineress,” something between a fortune-teller and an amateur apothecary. If you had a toothache, a lost treasure, or a future in need of reading, La Voisin and her professional peers would be there for you, mostly to exploit your vulnerabilities and your pocketbook. They offered a range of more sinister wares, too: grisly proto-abortions, love potions, poisoned posies, and more. Though arsenic was the poison of choice, the ingredients ran to the extravagant—even powdered diamonds were not unheard of. Repeat clients who came seeking a horoscope or herbal remedy might eventually walk out seeing the appeal of “darker” magic. Desperation can make strange things—poisoning one’s troubles away with arsenic, for example—seem reasonable.

La Voisin was a practitioner of some repute, allegedly known to virtually every woman in Paris, and prone to crapulence and excess. “She had as much money as she wanted,” a fellow divineress is quoted as saying, in the Bastille archives. “Every morning, long before she got up, [clients] would be waiting for her.” That she was arrested leaving mass was no accident. La Voisin, despite her nefarious trade, was a “high priestess of Christian congregations,” writes researcher Benedetta Faedi Duramy, “and a pious worshipper, who conceived her occult powers as a gift from God.” She would often encourage clients to pray for what they wanted—and then offered them seamier alternative means for bringing their prayers to life.

Sometimes alternative means were the only option for women of the period. They were treated, by law and practice, as secondary to men. Husbands had absolute legal, economic, and physical authority over wives. Adultery was illegal for all, but carried virtually no penalty for men. Women, however, could face imprisonment, beatings, or loss of dowry for sullying a husband’s honor and the legitimacy of his heirs. So women, it appears, turned to abortifacients or poisons to liberate themselves from unwanted pregnancies, lovers, or husbands. These potions often had uterine origins—menstrual blood or placenta—as if to liberate their users from the bindings of womanhood. Male authorities seem to have been particularly pricked by this effort for women to wrest some self-determination.

La Reynie learned a lot about this world from La Voisin after she was arrested. She named names. Professional peers were swiftly ushered into neighboring cells at the Château de Vincennes, until they held a veritable coven of members of the Parisian underworld. Her list of customers, too, was deeply troubling to authorities, and included prominent faces in court, including a countess whose husband had recently and mysteriously died. More shocking still, her confessions seemed to implicate one of the King’s former lovers, Madamoiselle des Oeillets, whose four-year-old daughter was one of his many illegitimate children. The King, already terrified of poisoning and exposure, panicked. He demanded from then on that the notes from La Reynie’s interrogations be put on loose pieces of paper. Those relating to sensitive matters could then easily be removed and burned, and kept from the eyes of a scandal-hungry public.

Eleven months after her arrest, La Voisin was burned alive in a public square now known as the Place de l’Hôtel de Ville. She was wheeled in after three days of torture, and as the flames began to lick at her feet, she swore profusely, frequent execution observer de Sévigné noted, and went very red in the face. “Paris is full of this kind of thing,” La Voisin said in her interrogations, echoing closely the foreboding words of de Brinvilliers, “and there is an infinite number of people engaged in this evil trade.”

By this time, La Reynie was becoming convinced that there was an epidemic of poisoning in Paris, with “a frightening amount of effort … devoted to its purchase, sale and manufacture,” writes Somerset. Staggered by the scale of the problem he was uncovering, he called on Louis XIV to declare a full-scale investigation, with a special commission to investigate and prosecute the cases: the Chambre Ardente. It would be expensive, certainly, but the health of the court, and potentially the royal family, seemed to hang in the balance. The King agreed.

The Chambre Ardente

The Chambre Ardente’s name came from its decor. The “burning room” was located deep in the bowels of the Arsenal, a royal munitions warehouse. (Today, entirely refurbished, it is a library.) It was lit only by flaming torches. Below windows shrouded in black cloth, 13 magistrates gathered to interrogate prisoners. The term, which first emerged in the mid-16th century, was a general one for an extraordinary court of justice, usually for the trials of heretics. Doctors and pharmacists were on hand to corroborate evidence and provide medical reports, alongside a smattering of additional staff, but the actual proceedings were conducted in absolute secrecy. Within these walls, during the course of the poison investigation following La Voisin’s arrest, five people were sentenced to life imprisonment, 23 banished, and 36 sentenced to death. Of those, 34 were executed: decapitated, hanged, strangled, broken on the wheel, or burnt alive. These were just a fraction of the 442 people charged with crimes related to “‘involvement in evil spells and composing, distributing, and administering poison.”’

The affair had begun with a woman of rank. Now, one after another, people of similarly high status were being hauled into the prison at Vincennes. Others, seeing flames in the future, fled, and lived the rest of their lives as fugitives elsewhere in the continent, never to return to France. The atmosphere at court began to change. The initial titillation of scandal gave way to depression. Overseas, the French court’s reputation changed, from one of sophisticated, if libertine, refinement to a place of vice and murder. The French public changed its tune as well, to disbelief and even mockery, as the poison-related inquisition cast out charges, but offered little conclusive evidence of the plague of poisonings itself.

But it continued. The Secretary of State for War, writing to a high-ranking Chambre official, said that no one should be spared questioning, no matter their position. “It would be worse if it was seen that his Majesty had given protection to people accused of crimes of the sort,” he wrote. The King, the official replied, was steadfast, and no one would be exempt in a manner this grave.

Athénaïs de Montespan

In late 1680, a name began to emerge from the widespread interrogations. Athénaïs de Montespan, then about 40, had once been the King’s favorite mistress. She came to court in the mid-1660s, and worked as one of the Queen’s ladies-in-waiting, having left her family and husband behind in the countryside. But de Montespan had higher aspirations: the bed, and heart, of the King. Though blessed with good looks—one Italian observer, upon seeing her blonde hair, azure eyes, and “aquiline but exquisitely formed” nose, described her face as “sheer perfection”—it seems to have been her tireless pursuit that won her her place under the King (as well as the simultaneous pregnancies of his wife and his previous favored mistress). Between 1669 and 1678, de Montespan bore him seven illegitimate children.

The claims attached to her name were various and shocking. She had poisoned the mistresses that preceded her. She had tricked the king into falling for her by shoveling aphrodisiacs into his food and drinks. Even that she had called for a bloody “black mass” in which, entirely naked, she had conjured the King’s love with a series of diabolical rites, including infanticide.

The King and La Reynie were shaken. It would be deeply humiliating for the King to be seen to have been persuaded by a love potion, especially as he had legitimized all their many offspring. (Two died in infancy, seemingly of natural causes.) But the commission had sworn to crack down on everyone, regardless of rank, position at court or proximity to the King. La Reynie and the King chose instead to stall for months in 1681. Then, after 16 hours of secret, undocumented argument, the King declared that he wanted the commission to continue, but that any evidence against de Montespan be thrown out.

It’s impossible to know whether this was because he believed in her innocence, or because he did not want to submit his surviving children by her to any further embarrassment. In court, the King had typically cast out those who may have posed a risk to him, but de Montespan hung on. She was still invited to parties and events, despite no longer being the King’s sexual partner. (Perhaps as a result of having borne so many children, she was no longer the slim young woman who sparked his romantic interest.)

The Dying Embers

The Chambre Ardente continued, and many more people were hanged. But the deliberative pause surrounding the accusations against de Montespan stripped away some of its fiery intensity. Commissioners were bored and disheartened, and the inquiry had lost some of its bite. Most of the key players had been executed, or chained up in fortresses and forgotten. In April 1682, La Reynie acknowledged that it might be time to let go. By July, the King, who had long since had enough, agreed. The entire enterprise had been built on many confessions extracted under torture—confessions that often bore no reasonable or demonstrable semblance to the truth. False leads proliferated and confusion grew. The primary victim of the poisoned air de Sévigné had so archly observed seems to have been the overactive and paranoid imaginations of those in charge.

The last of the secret documents about the Affair were burned, and the investigation was over. Life at court, with its parties and feuds, carried on. The myths and misconceptions that had set the scene for the Affair—about science, chemistry, magic, witchcraft, gender—seemed as much in place as ever. The dark magic of the underworld that the commission seemed to have opened up sank once again. De Montespan remained at court for many years before retiring to a convent in the early 1690s. La Reynie had been tasked by the King with a massive overhaul of the city’s moral fabric, a task scuppered, ultimately, by the monarch’s own interests. The police officer returned to municipal management, and spent his spare time collecting and cataloguing ancient Greek and Latin manuscripts.

The King’s fear of scandal overcame his fear of being poisoned, and ultimately the “burning room” was snuffed out. Returning his former life, he ruled judiciously and carefully—albeit with fewer romantic dalliances—for the longest reign of any European monarch, at 72 years. The Affair was at once over and unresolved.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook