An Illustrated History of the Orient Express

A postcard for the Orient Express, c. 1900. (Photo: Arjan den Boer)

The Orient Express, a luxury train service connecting Paris to Constantinople, was the figurehead of the Belle Époque, and remained closely connected to European history throughout the 20th century. The world’s most famous train gained an aura of thrilling intrigue—partly thanks to popular books and movies.

It was not only fiction, though: real artists and spies did travel by Orient Express and some actual murders did take place.

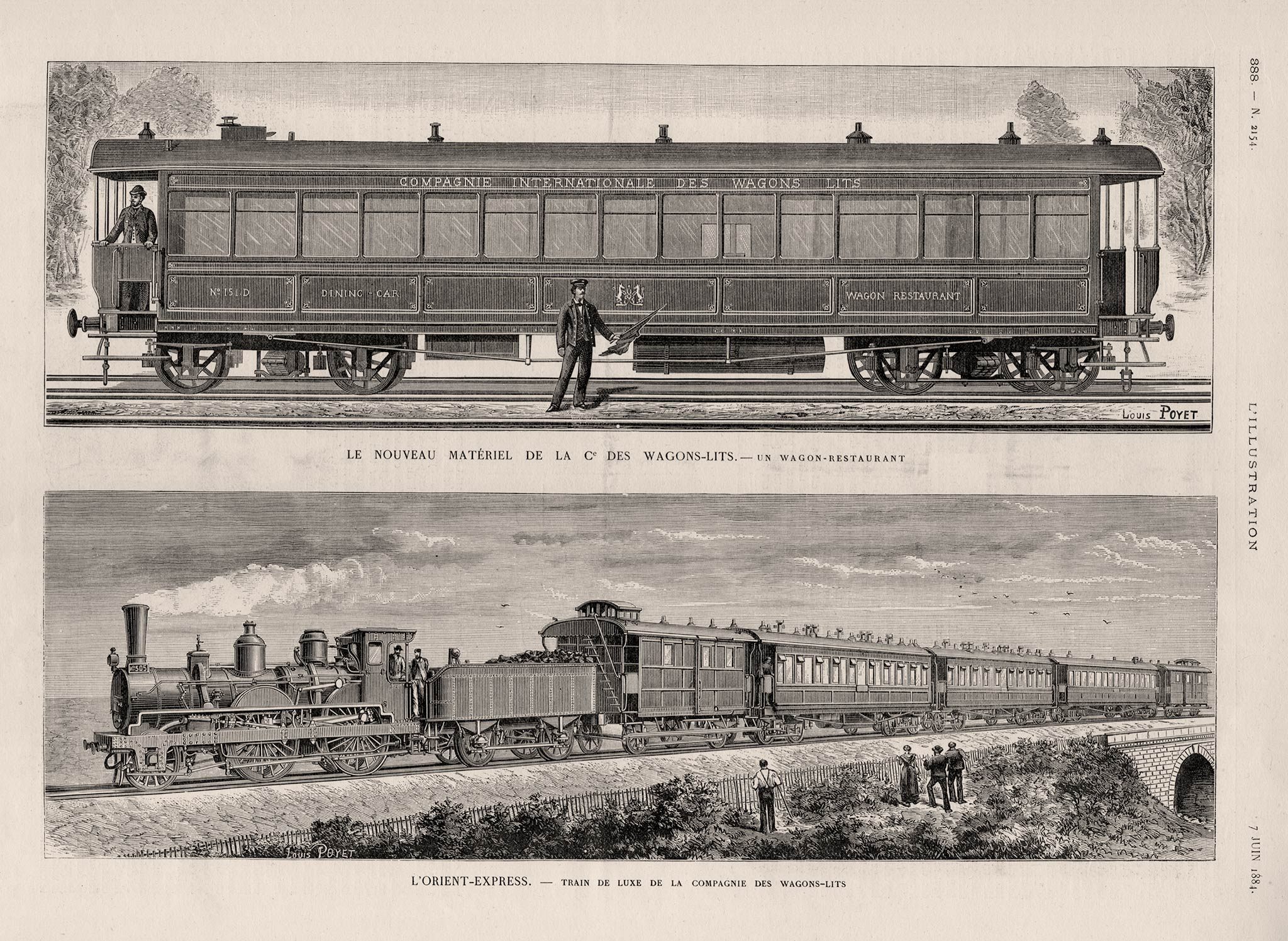

The first official Orient Express left Paris on October 4, 1883. Around 30 people were invited for the inauguration: officials, diplomats, journalists and railway directors. The host was Georges Nagelmackers, founder of the Wagons-Lits company. In 1868 the young Belgian banker’s son had traveled the US by Pullman sleeper and saw a gap in the European market.

After several experiments he reached an agreement with eight railway companies—from France to Romania—in 1883. They provided the rails and locomotives, Wagons-Lits supplied the sleeping and dining cars.

First Orient Express poster by Jules Chéret, 1888 (Photo: Arjan den Boer)

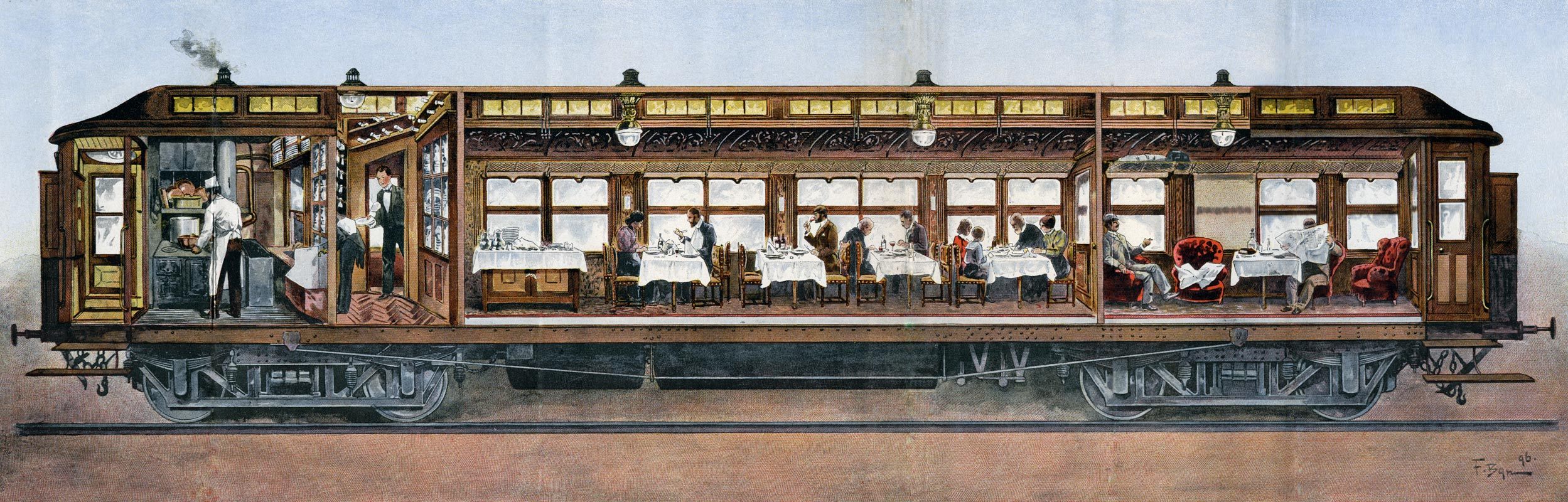

“The bright-white tablecloths and napkins, artistically and coquettishly folded by the sommeliers, the glittering glasses, the ruby red and topaz white wine, the crystal-clear water decanters and the silver capsules of the champagne bottles—they blind the eyes of the public both inside and outside,” wrote one of the guests, Henri Opper de Blowitz, about the inaugural dining car.

Bohemia-born De Blowitz was very well-traveled, spoke several languages and knew many prominent people. His publications, in which he revealed conspiracies or war plans, influenced the course of European history several times. De Blowitz not only reported on the interesting conversations he had with his travel companions, but also about the exquisite food aboard the Orient Express:

“It must be said, during the entire trip from Paris to Bucharest the menus vie with each other in variety and sophistication—even if they are prepared in the microscopic galley at one end of the dining car,” he wrote.

In a way, the Orient Express started running a few years too early, as the railway through Serbia and Bulgaria was not yet finished. Construction was delayed due to the political situation in the Balkans and the decline of the Ottoman empire. The last leg to Constantinople had to be made by steamer across the Black Sea. East and West finally were directly connected in 1888—traveling 3,000 kilometers in only 68 hours.

The first Orient Express featured in L’Illustration, 1884 (Photo: Arjan den Boer)

Golden Age

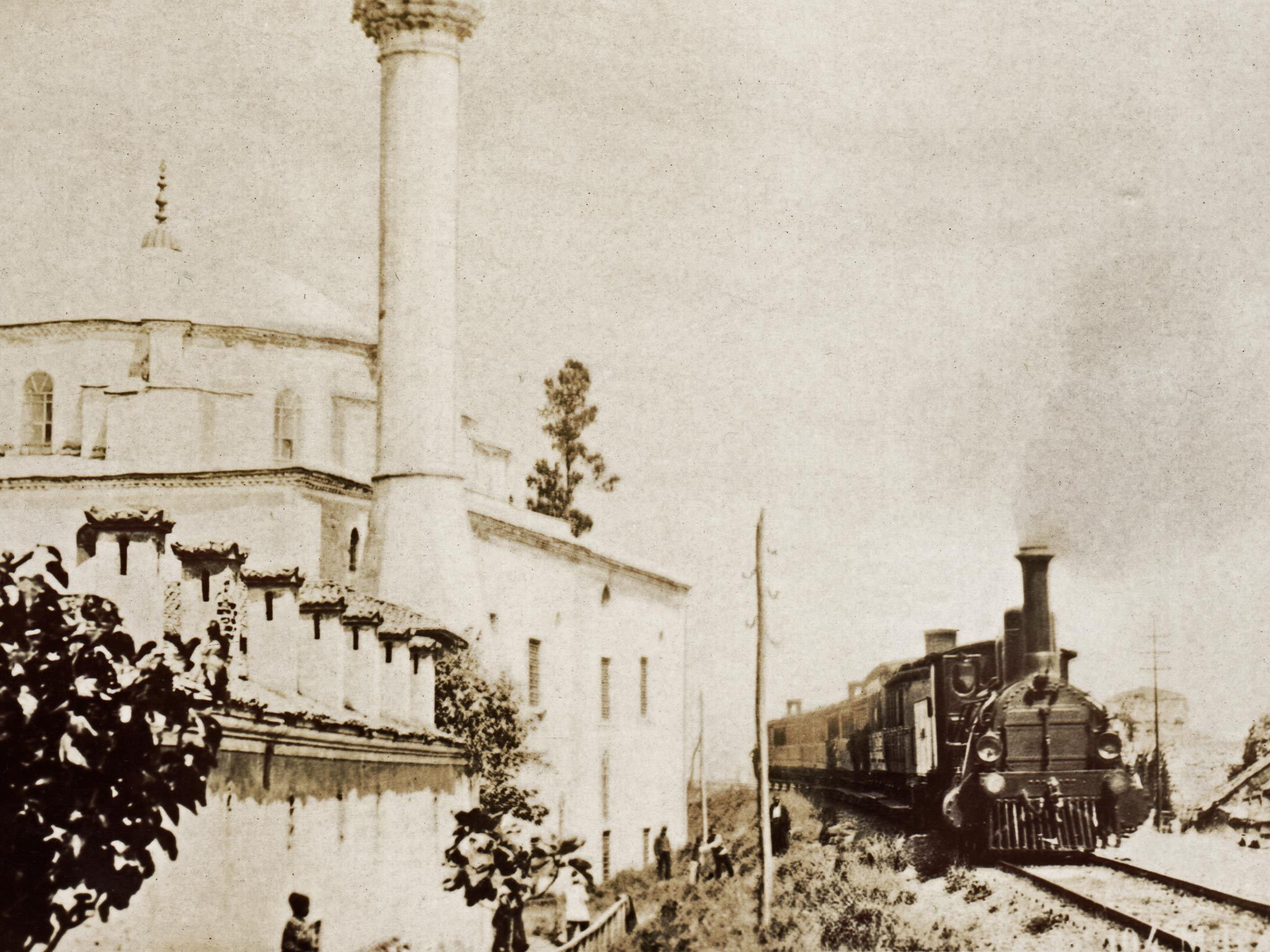

The opening of the new Constantinople station in 1890 marked the beginning of the Golden Age of the Orient Express. The direct train between Constantinople and Paris was a fast alternative to boat travel — but only for those who could afford it. Converted to today’s value, a ticket cost around 1,750 euros, a quarter of the annual income of the average Frenchman.

Even with the Ottoman empire in decline, the capital of Constantinople was a hive of activity around 1900. Turks, Greeks, Armenians and Jews all lived together. The Orient Express brought in Western diplomats, investors and artists.

As the exotic final destination, Constantinople captured all the attention. But the Orient Express was primarily a link between the major Central European cities. The luxury train ran daily from Paris to Munich, Vienna and Budapest. Constantinople was only the terminus twice a week.

The Orient Express passes the Little Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, c. 1895. (Photo: Arjan den Boer)

Simplon Orient Express

The First World War brought an abrupt end to a period of prosperity, cosmopolitism and cultural blossoming. On the day when Austria declared war on Serbia, the Orient Express also came to a standstill. During the war Germany and its allies started running their own luxury train to Constantinople.

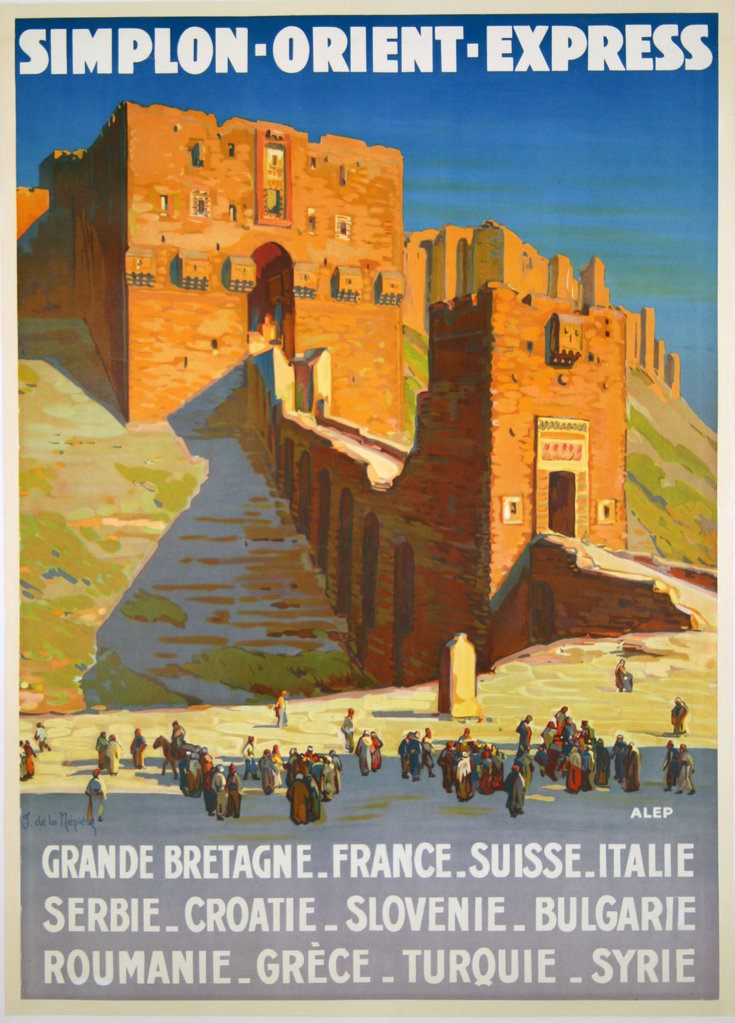

After the war, the railway map of Europe was redrawn. The classic Orient Express was limited to Bucharest, while the victors introduced a new train bypassing Germany: the Simplon Orient Express. After traversing the Swiss Alps via the Simplon Tunnel, it ran through Italy, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey.

Simplon Orient Express map, c. 1932. (Photo: Arjan den Boer)

The Versailles Treaty granted the Simplon Orient Express a 10-year monopoly on the Paris-Constantinople connection. After the introduction of steel carriages with fancy Art Deco interiors, the new train became particularly popular with diplomats, artists and writers.

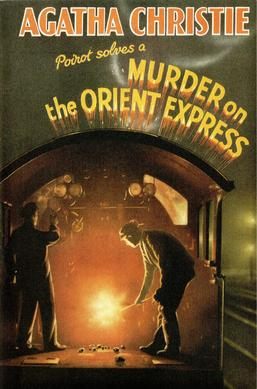

In 1929 the Simplon Orient Express was snowed in for five days at a small station in Turkey. This incident inspired Agatha Christie, although she chose Yugoslavia as the location for her 1934 novel Murder on the Orient Express. In fact, the first known murder on the train did not occur until one year after the publication of her novel.

German fold-out cross-section of an Orient Express dining car, 1896. (Photo: Arjan den Boer)

In 1935 a wealthy Romanian woman was robbed by her compartment companion and pushed through the open window of the Orient Express. Maria Farcasanu, director of a Bucharest fashion school, was on her way to her husband, the Romanian military attaché in Paris. Her body was discovered along the railway in central Austria. Her belongings were also found, except for a precious silver-fox scarf.

A Swiss policeman spotted the silver-fox scarf by chance. The woman wearing it had gotten it from the 23-year-old student Karl Strasser. He was sentenced to death in Austria, but was eventually imprisoned for life.

A poster for Simplon Orient Express. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Near East

No Orient Express ever went beyond Istanbul—as Constantinople was renamed by the Turkish leader Atatürk. However, in 1930 the Taurus Express was introduced as an extension to the Simplon Orient Express. Travelers first had to cross the Bosphorus at Istanbul. At the Haydarpasha station connections were provided to Syria, Iraq, Palestine and Egypt, requiring several transfers, including taxi or bus services. In the advertising, though, the Simplon Orient Express was touted as a three-continent train.

In her memoirs of Syria, where her husband was an archaeologist, Agatha Christie contrasted the luxury of the Taurus Express to the desert hardship:

The train starts! I follow the conductor along the corridor. He flings open the door of my compartment. The bed is made. Here, once more, is civilization. Le camping is ended. The conductor takes my passport, brings me a bottle of mineral water, says: We arrive at Alep at six tomorrow morning. Bonne nuit, Madame.”

The Orient Express in Turkey, in 1970. (Photo: Mouliric/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Cold War

The Orient Express only narrowly recovered from the Second World War. Many Wagons-Lits carriages had been lost and infrastructure was severely damaged. Reconstruction of the railways was partially funded by the U.S. Marshall Plan.

During the Cold War, the Orient Express was, despite some interruptions, one of the few links between Eastern and Western Europe. While Eastern Bloc citizens were not allowed to travel freely, strict border controls made it difficult to travel to Eastern Europe. The Orient Express was still important for diplomatic traffic, though, and occasionally brought political refugees to the West.

The first edition cover of Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express. (Photo: Collins Crime Club/WikiCommons)

One of the first American deaths linked to the Cold War took place aboard the Orient Express. In 1950 Eugene Simon Karpe fell off the train under suspicious circumstances in a tunnel near Salzburg, Austria. Captain Karpe was the U.S. naval attaché in Bucharest, Romania, and was traveling with sensitive papers about spy networks in Eastern Europe in his briefcase.

Was Karpe’s fatal fall an accident or deliberate? Passenger interrogations and an autopsy provided no answer. The case, which resembled a thrilling movie script, attracted much attention in the Western press. In 1952 a Romanian student claimed to have committed the murder with two others for a “foreign organization,” but there were doubts about his confession. A decade-long U.S. investigation could not unravel the exact circumstances.

Istanbul Sirkeci station (1891), terminus of the Orient Express. (Photo: Arjan den Boer)

Visa Obstacles

The strict visa policies in communist Bulgaria formed a major obstacle for Simplon Orient Express travelers going on to Turkey. The number of Western passengers could usually be counted on one hand, and were often American and British diplomats and intelligence officers. One of them was the former naval intelligence office Ian Fleming, who partly based his 1957 James Bond thriller, From Russia with Love, on Eugene Karp’s tragic, last train journey.

Between 1951 and 1953, Bulgaria completely blocked the Simplon Orient Express due to conflicts with neighboring countries. Once Bulgaria allowed the train to enter again, art students were deployed to beautify the surroundings of the railway line in order to make a good impression on Western travelers. One of these students was later to become the renowned artist Christo.

The Orient Express shown at a border station between Liechtenstein and Switzerland. (Photo: Murdockcrc/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 2.5)

Decline

From the 1960s onwards the Orient Express gradually lost its shine. In 1977, nearly 100 years after the first journey, the last direct train left Paris for Istanbul. This spartan Direct-Orient mainly carried hippies and migrants. There was no dining car anymore; passengers had to bring their own supplies for several days.

“The Orient Express really is murder,” complained travel writer Paul Theroux of the frugal surroundings. The contrast to the sophisticated 1930s Simplon Orient Express could not have been greater.

However, publicity surrounding the last trip resulted in a revival: the private Venice-Simplon Orient Express (VSOE), started by an American-British entrepreneur. Since 1982 this luxury “rail cruise” has chugged between London, Paris and Venice using restored Wagons-Lits carriages.

An Orient Express luggage tag. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Last remnant

While nostalgia trains attracted much attention, the last remnant of the original Orient Express continued in silence. As an unremarkable night train it still ran between Paris, Vienna and Budapest. Already truncated to Strasbourg-Vienna, the EuroNight Orient Express was discontinued in 2009. After 126 years, aviation and high-speed trains had put an end to the classic Orient Express.

British journalist Robin McKie witnessed one of the last arrivals at Vienna: “A small group of disconsolate wanderers emerged from the Orient Express and trudged off into the grey morning, by now utterly uninterested in the fate of the historic train on which they had just traveled.”

This article is based on the Orient Express History iPad app by Arjan den Boer. This app tells the fascinating story of the world’s most famous train, richly illustrated with historical images and interactive elements.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook