Ancient Mesoamericans Calmed Down and Hooked Up in Sweaty Steam Baths

Temazcales helped indigenous people let off steam, until colonialism came along.

This week, we’re remembering historic leisure activities—ways that people kicked back, chilled out, and expressed themselves throughout the centuries. Previously: Ancient hominids painted, and the swole women of Sparta wrestled, danced, and drank.

In ancient Mesoamerica, bathing was about more than cleanliness: It was about pleasure. The years before the arrival of Spanish colonizers were the heyday of the temazcal, a volcanic sweat lodge that allowed visitors to cleanse themselves not by immersion but by steam. In other words, every bath felt like what we would now consider a spa day.

Temazcales existed in the Americas for at least 700 years before the arrival of Spaniards in 1519, according to anthropologist Casey Walsh, who wrote Virtuous Water: Mineral Springs, Bathing, and Infrastructure in Mexico. Temazcal comes from the word temāzcalli, which translates to “house of heat” in the Nahuatl language (also known historically as Aztec). Most temazcales resembled domed structures, some just large enough for a family and others for half a village. But they weren’t meant for private use. “You wouldn’t build a temazcal for just one person,” Walsh says. The indigenous people of Mesoamerica often constructed them out of volcanic rock, which were practically fireproof. But researchers have found traces of other ancient temazcales made of adobe, sticks, and even grass, Walsh says.

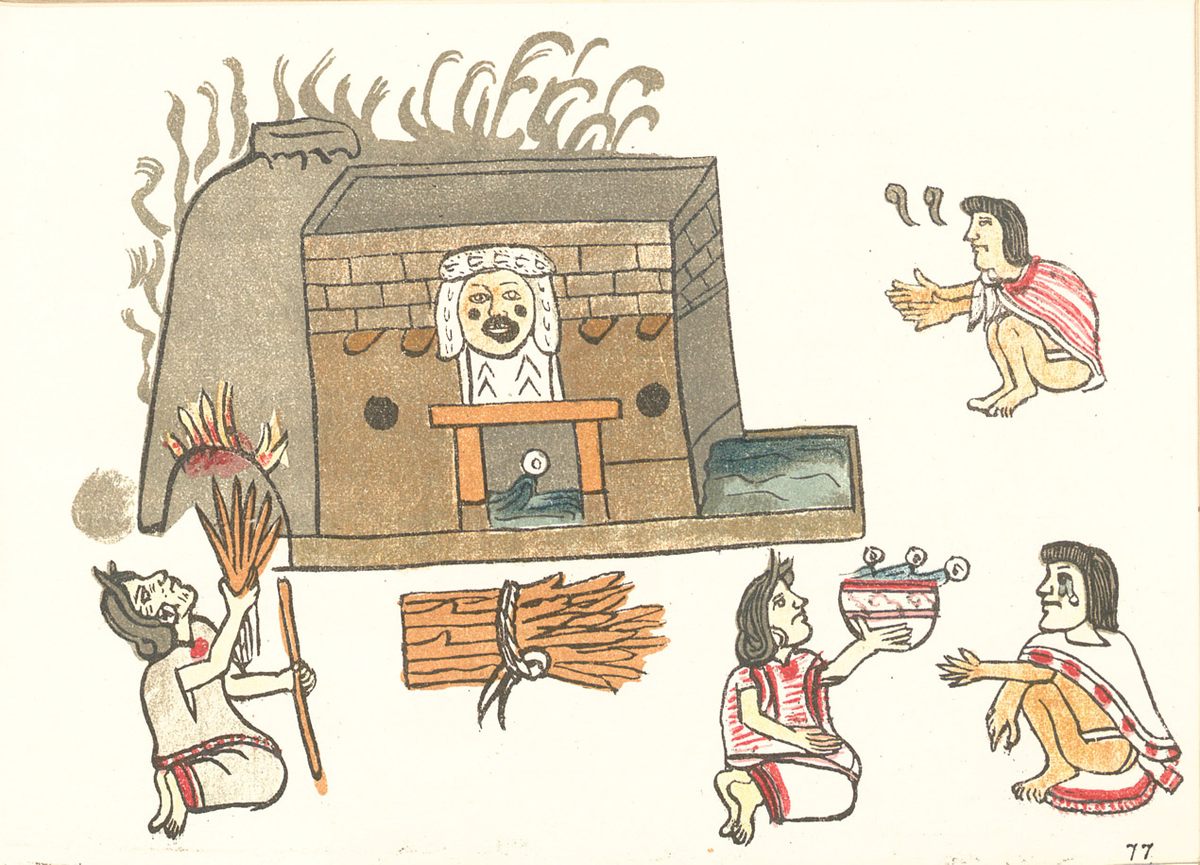

A common way for bathers to create steam was by carrying superheated stones from an outside fire into the center of the temazcales, and then dousing them in cold water to create glorious, wafting clouds of steam. But other temazcales were adjoined by an exterior fire chamber, ensuring that heat from the flames would pass through the porous volcanic rock, Walsh writes. Then all you had to do was sit back, relax, and secrete profuse, gushing cascades of your own sweat.

To some, it may seem counterproductive to bathe in sweat. “Today, we have an exaggerated notion of cleanliness and hygiene and sanitation that’s wrapped up with notions of disease and germs,” Walsh says. “But for most of history, our ancestors bathed not to wash things off but to absorb the environment.” In Mesoamerica, people bathed to cleanse their bodies of maladies, sicknesses, and illnesses, as well as to recharge and recuperate after battle.

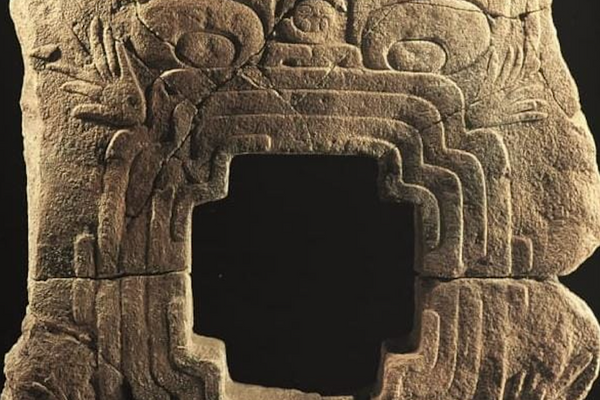

Though they no doubt felt incredible, temazcales were steeped in ritual and ceremony. When a person stepped through a doorway into a temazcal, they also symbolically passed through a portal to the underworld. Many temazcales in pre-conquest Mesoamerica were adorned with a statue of Tezcatlipoca, the god of healing and the underworld, or Tocitzin, also known as the grandmother of the temazcal. “They saw this as a place to engage with the spirits of the underworld,” Walsh says. “Especially spirits of water and spirits of fertility.”

Naturally, temazcales also served another purpose. Like other kinds of bathhouses across the world, temazcales were spaces for sex. “In ancient Rome, bathhouses were seen as places to conduct politics and hook up,” Walsh says, adding that the steam lodges were not separated by gender. “Temazcales were just the same.”

In fact, in the 1581 text The History of the Indies of New Spain, the Dominican friar Diego Durán noted that at many temazcales, it was considered a bad omen for a person to bathe without a person of the opposite sex around, writes historian Pete Sigal in The Flower and the Scorpion: Sexuality and Ritual in Early Nahua Culture. Durán wrote, “I would not hold all this to be so unchaste and immodest if the husband entered with his wife, but at times there is so much confusion and laxity that, mingled and naked as they are, there cannot fail to be great affronts and offences to our Lord.”

Not surprisingly, when the colonizers arrived, they ruined everything. In the 1500s, Spanish Catholics had cracked down on bathhouses in Spain as an assault on religious purity, Walsh writes. So in the Americas, Spanish missionaries took note of this intimate sort of socialization. Their disapproval survives in surveys they conducted with indigenous bathers, to learn more about sexual practices the Church believed to be sinful. In 1569, in an attempt to stamp out these practices, a priest penned a questionnaire for Native Americans to answer in confession, asking respondents with whom they carried out which carnal acts.

In the tradition of more recent bathhouses, temazcales also served as a place for queer sex and hookups. One rather disapproving 16th-century priest wrote, “They committed other terrible wicked acts in the baths…Many men and women, and women with men, and men with men illicitly used and got into the bath,” notes Alejandro Tonatiuh Romero Contreras in “Visiones sobre el temazcal mesoamericano: Un elemento cultural polifacético,” a paper published in Ciencia Ergo Sum.

Over the next few centuries, as the colonial government rebuilt Tenochtitlán into its new capital of Mexico City, it also tried to crack down on temazcales, Walsh writes. In 1725, the government prohibited temazcales in the indigenous pueblo of San Juan Teotihuacán. They wanted to purge the temazcal of its indigenous heritage and redefine it as a space of cleanliness, not socialization. “They believed the proper use of [the bath] should be about healing and cleaning, not about religious, spiritual, or sexual pleasure,” Walsh says. But despite the colonial government’s best efforts, temazcales persisted for a while as an underground space for indigenous spirituality and sexual freedom, Walsh writes.

The baths became much less common as the new government pressured indigenous people to assimilate and modernize—a very un-chill end to one of Mesoamerica’s most relaxing spaces, and proof of one of history’s evergreen truths: colonizers are the absolute worst. But if you’re interested in sweating it out like they did in Mesoamerica, temazcales are still around and quite the tourist attraction.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook