Why More Animals Don’t Use Their Tails as Weapons

By wielding their built-in defenses, some prehistoric creatures thwacked enemies hard enough to crack bone.

The Ankylosaurus magniventris, which stomped along at the sunset of the Cretaceous period, was christened for its heft—the name translates, roughly, to “great belly”—but it’s perhaps especially notable for its no-nonsense tail. The dinosaur was clad with hard plates, and, thanks to interlocking vertebrae, could swing its club-and-knob tail laterally at an angle of 100 degrees, landing with a thunk hard enough to crack bone.

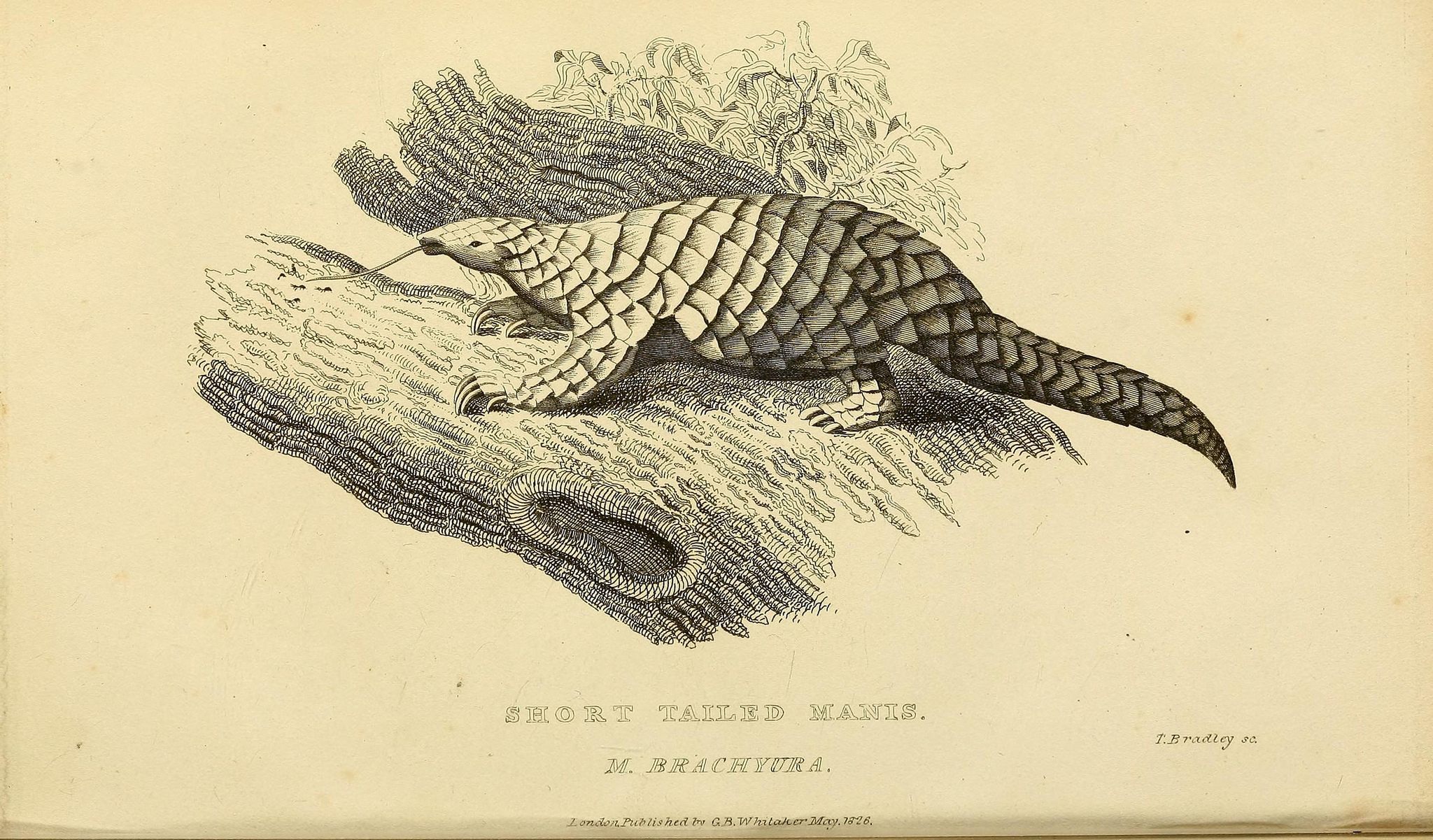

Creatures boast many built-in defense mechanisms, but most of these, such as horns, are precariously close to the soft and fragile tissue of the face or brain. By comparison, wagging a weaponized tail, heavy with armament, seems like a pretty smart move—enforcing a comfortable perimeter without putting the cranium on the line. But spiked-and-studded tails and lashing behaviors are relatively uncommon, both in the historical record and in extant species. Today, porcupines, pangolins, aardvarks, and some lizards wield their tails as weapons against predators, but otherwise, the trait has gone the way of the dinosaurs. Researchers from the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences wondered why.

For their study, newly published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, the scientists studied 286 species and concluded that tail-lashing and weaponized tails are each correlated with specific anatomical and ecological factors. Tail-whipping “appears to be a strategy of last resort,” the authors write, a backup plan deployed after other strategies such as vigilance, camouflage, and escape have failed. (Since direct contact with predators is a dicey proposition, the authors add, selection pressures may have been stronger for other anti-predator strategies that preserve a wider berth.)

Historically, taxa with weaponized tails seem to have shared a suite of traits: They tended to be large herbivores—topping 200 pounds—and protected by carapaces, spikes, or other armored attributes. They were also stiff enough to stay stable while hauling their bulbous tails around. Very few creatures tick all the boxes.

“It’s rare for large herbivores to have lots of bony armor to begin with, and even rarer to see armored species with elaborate head or tail ornamentation because of the energy cost to the animal,” said coauthor Victoria Arbour, now a postdoctoral fellow at the Royal Ontario Museum, in a statement. “The evolution of tail weaponry in Ankylosaurus and Stegosaurus required a ‘perfect storm’ of traits that aren’t seen in living animals, and this unique combination explains why tail weaponry is rare even in the fossil record.” The upshot: You’re unlikely to find yourself decked by a barbed tail any time soon.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook