Don’t Call Annie Smith Peck a Woman Mountain Climber

The 19th-century mountaineer and suffragist competed with men and women alike to find the apex of the Americas.

For Women’s History Month, Atlas Obscura is living on the edge with Women of Extremes, our series dedicated to those who dared to defy expectations and explore the unknown.

On May 4, 1912, women in white paraded through the streets of New York City. Some 10,000 people marched to Carnegie Hall, where leaders in the women’s suffrage movement rallied their supporters. Just outside, another woman spoke from a makeshift perch. “In the vestibule,” read a New York Times account of the event, “Miss Annie S. Peck, the mountain climber, mounted a chair and led a meeting of her own.” Holding the flag of the Joan of Arc Equal Suffrage League, Peck proudly told her audience this was “the banner she had planted 21,000 feet above the sea.”

Ten months earlier, a 61-year-old Peck had climbed to the eastern summit of Coropuna, an ice-covered volcanic complex in Peru, where she stuck a flag reading “VOTES FOR WOMEN” into the ground. The expedition was a milestone in both her 30-year climbing career and a lifetime devotion to women’s rights. But Peck balked at the suggestion that her accomplishments should be qualified by gender, once telling a reporter, “I have climbed 1,500 feet higher than any man in the United States. Don’t call me a woman mountain climber.”

Peck was born in 1850, two years after the first women’s rights convention at Seneca Falls. Growing up in Providence, Rhode Island, her world was shaped by the ideas of abolitionists and suffragists. The youngest of five children, Peck watched her older brothers go off to study medicine, engineering, and classics, and saw no reason that she should not follow suit.

But in the 1870s, options for a woman in want of a college degree were limited. Though Peck hoped to attend Brown University, the school was still decades away from accepting its first female students. She enrolled at the University of Michigan instead, waving off objections from her family.

After finishing an undergraduate degree in classical studies, Peck returned for a master’s, then went abroad to study archaeology in Athens. The mountains she saw while traveling in Europe inspired Peck to take up climbing. Upon seeing the Matterhorn for the first time, she was “seized with an irresistible longing to attain its summit.”

Ten years later, in 1895, Peck returned to Switzerland to set foot on the 14,692-foot peak. Though she was accompanied by a pair of experienced guides, summiting was no easy feat. Like many hikers, the climbing team dropped gear as they traveled up the mountain to make their packs lighter. Unlike many hikers, one of the items Peck discarded was the skirt she had initially worn over her knickerbockers.

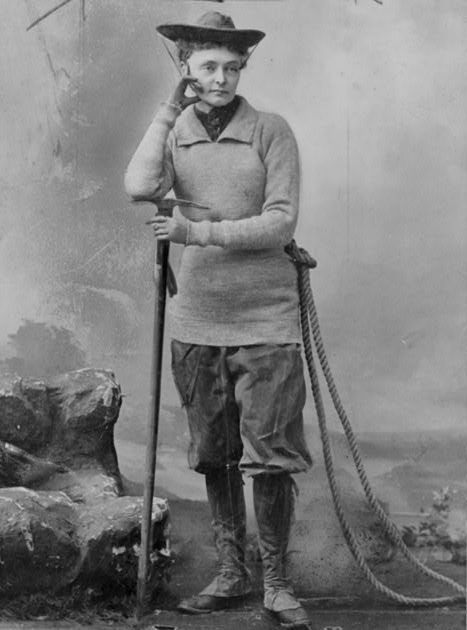

Peck was not the first woman to climb the Matterhorn. She wasn’t even the first to do it in pants—American climber Meta Brevoort had worn a similar outfit when she climbed the Alpine peak in 1871. But Peck was the first to make her climbing costume part of her public persona, posing for a studio portrait wearing knickerbockers and a tunic, a rope tied around her waist and an ice ax under her elbow. According to Hannah Kimberly’s 2017 biography of Peck, A Woman’s Place is at the Top, “the iconic illustration of a woman climber in pants helped make Annie S. Peck a household name.”

By her late 40s, Peck had conquered several more European peaks, the tallest mountain in Mexico, and an active volcano. She funded her expeditions by scraping together donations from friends, selling stories to magazines, and lecturing on archaeology, geography, and mountaineering. “She filled halls—both the floor and the balconies—with captive audiences,” writes Kimberly, “who came to hear a birdlike woman who did not fit the husky mountain-climber image they had in mind.”

Though she had gained acclaim, Peck wasn’t satisfied with records that only compared her achievements to other women. She set her sights on mountaineering’s loftiest pursuit: first ascent. “In a sport where the stakes are often high, first ascents raise them even higher,” writes Peter Mortimer, director of the documentary First Ascent, in Alpinist Magazine. “The climber is venturing into unknown and unpredictable terrain… to leave a permanent mark on climbing.”

In 1903, Peck traveled to South America to “attain some height where no man had previously stood.” Specifically, she was after Huascarán in the western Andes. In her account A Search for the Apex of America, Peck included a detailed list of supplies: layers of wool clothing, heavy boots, sunglasses, a thick sleeping bag, a lightweight tent, cured sausages, dried beans, and chocolate—this last item the only supply deemed “absolutely essential.”

Unfortunately, she would not find success on that trip, nor the next one. It wasn’t until a third attempt in 1908 that Peck reached the northern peak of Huascarán, along with two Swiss guides. Though pleased with completing the first recorded ascent of the mountain, Peck was disappointed to discover that her estimate of the elevation had been off by a few thousand feet. She had not, in fact, climbed the tallest mountain in South America. (That title belongs to Argentina’s Aconcagua.)

Three years later, Peck returned to Peru to plant her flag atop Coropuna. In the years that followed, she continued to write, lecture, and travel while joining the fight for women’s suffrage. Health issues had started to put limits on her climbing, but the ever-intrepid Peck found new ways to scale heights: In 1929 and 1930, she spent seven months traveling South America by plane. When Peck’s book Flying Over South America: Twenty Thousand Miles by Air was published in 1932, Amelia Earhart endorsed it, writing, “I am only following in the footsteps of one who pioneered when it was brave just to put on the bloomers necessary for mountain climbing.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook